Welcome to the KanjiDB Japanese character database website!

The main advantages of our project:

- Only here is unique data:

a)

all compound words without exception (and these are the majority in the Japanese language) are divided into types of readings by color: onny reading, kun reading, non-standard reading

b)

a unique method for assessing the popularity of a word is presented - each word has a rating, which is based on the frequency of use of this word in the Japanese segment of the Internet or its occurrence in Japanese newspapers - you can estimate how popular a particular word is and decide which words to learn first.

c)

most words indicate the syllable on which the stress falls.

Japanese tonic stress is one of the most difficult aspects of learning the language, largely due to a lack of information. d)

hieroglyphs are classified according to many characteristics thanks to a system of categories: new ones are added to the traditional division by readings, by keys, features and constituent elements: first of all, this is a division by lessons of popular Russian textbooks, and in the future there will be a division by semantic and other characteristics ( animals, colors, nature, mostly adjectives, mostly verbs, etc.)

— Orientation to the study of hieroglyphs and words:

a)

many hieroglyphs in the database have mnemonic story tips, thanks to which you can remember the spelling.

Moreover, hints are added both by the database authors themselves and by ordinary users - for each sign you can leave your own comment with your own version of the hint. b)

thanks to the system of personal categories, you can create any sets of signs yourself - sort hieroglyphs into shelves and select signs for training, both from publicly available category lists and from those compiled by you.

c)

a method for memorizing a hieroglyph according to the principle: the system gives you the Russian name - you tell it everything else, including the spelling.

options for memorizing kanji, when you give readings to write, showed their ineffectiveness - students could recognize the sign, but could not write. Now you can learn hieroglyphs and be sure that you really remember them. d)

the statistics of your checks are displayed on the hieroglyphs page and based on it you can conclude whether you know the sign or not. The most effective learning program is when you decide for yourself whether you have learned something or not. (in the future, the system will offer to mark some signs as learned - but the decision will still be up to the user).

And this is just what has already been done. In the future, the database will be significantly expanded and updated with new functions.

Japanese characters. Classification of hieroglyphs

Japanese characters. Classification of Japanese characters.

When starting to study the hieroglyphs of the Japanese language, many encounter difficulties in memorizing the hieroglyphs. This often happens because those starting to learn the Japanese language do not know that hieroglyphs have patterns of formation and they have their own classification, and this greatly facilitates the process of mastering and memorizing hieroglyphs. Let's look at what types of hieroglyphs there are and how they are classified.

There is a misconception that there are Chinese, Japanese and Korean characters. In fact, the characters common in Southeast Asian countries are mostly Chinese.

The characters came to Japan from China and were called 漢字/kanji. Japanese characters have one (Chinese) reading and kun (Japanese) reading.

Onny (Chinese) readings of characters in Japanese are different from Chinese readings in Chinese.

Hieroglyphs that are independent words are read in kun (Japanese) readings, but if a word consists of several hieroglyphs, then it is usually read in on readings. For example, let’s take the character for “path” 道:

Native Japanese words are included in the word group called wago (和語), and loanwords that are read in onic readings are included in the word group kango (漢語).

How are hieroglyphs classified?

In the Chinese dictionary “Shouwen” (1st century AD), all characters were divided into six categories. These categories are called "rikusho" (六書):

1. Figurative signs or pictograms – sho:kei (象形).

2. Index fingers – shiji (指事).

3. Ideograms, i.e. clear in meaning – kaii (会意).

4. Phonideographic, i.e. image and sound – keisei (形声).

5. Derivative signs (which are used figuratively and meaningfully) – tenchu: (転注).

6. “Borrowing”, i.e. phonetic use of the character – kasha (仮借).

Pictograms

Pictograms are images of objects that were subsequently schematized. For example, let's take the character 人 hito, which means “person.” This hieroglyph is a schematic image of a person in profile.

Or, for example, the hieroglyph 火 hi “fire” depicts the flames of a fire, and the hieroglyph 川 kawa “river” is an image of river streams.

In the character for "tree" 木 moku, even now one can distinguish a trunk, branches and leaves.

The history of the origin of the hieroglyph “white” – 白 haku/shiroi – is interesting. To convey the meaning of “white” in writing, an image of an acorn was used due to its internal whiteness. Subsequently, this sign acquired a modern look.

Demonstrative characters

Indicative hieroglyphs indicate the direction. Thus, the hieroglyph 上 (ue) “up” consists of a horizontal line and a vertical line extends upward from it, in turn a small dash extends from it to the right (in the ancient writing there was no small dash). The reverse of the character for “up” is 下 shita “down”.

The character for “pass” 峠 to:ge was created in a similar way. In addition, this group includes hieroglyphs denoting numbers.

Ideograms

A group of hieroglyphs that convey a state or function. Here a complex hieroglyph consists of two or more simple characters. For example, the character for “rest” 休 kyu: / yasumu, consists of the character 人 hito “person” and the character for “tree” 木 ki / moku, i.e. the meaning of the ideogram is obtained - “to rest under the shade of a tree.”

Phonoideograms

Most of the signs used in the past are phonoideographic hieroglyphs. They are still used today. In this group, the reading of the hieroglyph coincides with the reading of one of its parts, which is called “phonetic”, the other part of the hieroglyph is called “determinative”, it defines the concept of the hieroglyph.

For example, a group of characters with a common reading じ / ji:

寺/temple 時/time 持/keep 侍/samurai. As you can see, in this group of hieroglyphs the same sign 寺/ji is found, which is the key to reading these characters.

Derivative signs

A group of hieroglyphs with a figurative or derived meaning. This includes signs that have come to be used in a meaning different from the original one. For example, the character 楽 gaku is part of the word “music” - 音楽/оngaku. Later, this character acquired the meaning “to enjoy, to have fun” (楽しむ/tanoshimu), i.e. listening to music is a pleasure.

Phonetic signs

Hieroglyphic signs that are used as an analogue of the syllabary alphabet. For example, the word “Russia” /ロシア is written with consonant hieroglyphs 露西亜, “Paris” /パリ – 巴里, etc.

This is how hieroglyphs are classified. With the help of such a classification, the process of memorizing and understanding hieroglyphs is definitely facilitated.

Author of the article: Anna Belkova

This is a useful read:

- Online Japanese lesson for free

- Japanese cases. From simple to complex. Accusative case - particle を/wo/o

- Continuous form of verbs

Tagged classification of Japanese characters Japanese characters Japanese characters and their meaning Japanese characters pictures Japanese characters in Russian Japanese characters with translation Japanese language hieroglyphs

Japanese characters and their meaning

Kanji

(Japanese 汉字 - kanji, “Chinese characters”) - hieroglyphic writing, an integral part of Japanese writing.

Japanese characters

were borrowed by the Japanese from China in the 5th and 6th centuries. To the borrowed characters were added hieroglyphs developed by the Japanese themselves (国字 - kokuji). In addition to hieroglyphs, two components of the alphabet are also used for writing in Japan: hiragana and katakana, Arabic numerals and the Latin Romaji alphabet.

Story

The Japanese kanji term (汉字) translates to "Han (Dynasty) Marks". It is not known exactly how Chinese characters came to Japan, but today the generally accepted version is that the first Chinese texts were brought in at the beginning of the 5th century. These texts were written in Chinese, and in order for the Japanese to be able to read them using diacritics in compliance with the rules of Japanese grammar, the kanbun system was developed - kanbun or kambun (汉文) - originally meaning "Classical Chinese Composition".

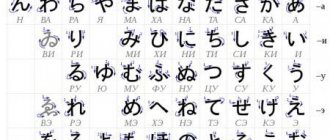

The Japanese language at that time did not have a written form. To record native Japanese words, the writing system Man'yōshū (万叶集) was created, the first literary monument of which was the ancient poetic anthology "Man'yōshū". The words in it were written in Chinese characters according to their sound, not their content.

Man'yōshū (万叶集) rus. Manyoshu, written in hieroglyphic cursive, evolved into hiragana, a writing system for women for whom higher education was almost inaccessible. Most of the literary works of the Heian era with female authorship were written in hiragana. At the same time, Katakana arose: students from monasteries simplified Manyoshu to a single significant element. These writing systems, katakana and hiragana, were derived from Chinese characters and subsequently developed into syllabic alphabets, which are collectively called Kana (仮名) or Japanese syllabary.

Hieroglyphs in modern Japanese are used mostly to write the stems of words in nouns, adjectives and verbs, on the other hand, hiragana is used to write inflections and endings of verbs and adjectives (see okurigana), particles and words in which it is difficult to remember the hieroglyphs. Katakana is used to write onomatopies and gairago (loan words).

Katakana began to be used relatively recently to write borrowed words. By the end of World War II, such words were written in characters according to their meaning (烟草 or 莨 tabako - “tobacco”, literally “grass that smokes”) or according to their phonetic sound (天妇罗 or 天麸罗 tempura - fried food of Portuguese origin). The last method of writing in hieroglyphs is called ateji.

Japanese innovation

At first, Chinese and Japanese characters were practically no different from each other: the latter were traditionally used to write Japanese text. However, nowadays there is a big difference between Chinese Hanzi and Japanese Kanji: some characters were created by the Japanese themselves, and some received different meanings. In addition, after World War II, many Japanese characters were simplified in their writing.

Kokuji (国字)

Kokuji (国字 - "national characters") are characters of Japanese origin. Kokuji is sometimes called Wasei Kanji (和制汉字 - "Chinese characters created in Japan"). In total, there are several hundred kokuji. Most of them are rarely used, but some have become important additions to the written Japanese language. Among them:

峠 (とうげ) toge (mountain pass)

榊 (さかき) sakaki (sakaki tree from the genus Camellia)

畑 (はたけ) hatake (dry field)

辻 (つじ) Tsuji (crossroads)

働 (どう/はたらく) do, Hatar(ku) (physical work)

Most of these “national characters” have only Japanese readings, but some were borrowed by the Chinese themselves and also acquired onne (Chinese) readings.

Kokkun (国训)

In addition to kokuji, there are characters that have different meanings in Japanese than in Chinese. Such characters are called kokkun (国训- “[signs of] national reading”). Among them:

冲(おき) OKI (open sea; Chinese rinse)

森(もり) Sea (forest; Chinese: majestic, lush)

椿(つばき) Tsubaki (Japanese camellia (Camellia japonica) Chinese Ailanthus)

Old and new characters (旧字体,新字体)

The same character can sometimes be written in different styles: old (旧字体, kyujitai - “old characters”; in the old style 旧字体) and new (新字体, shinjitai - “new characters”). Below are several examples of writing the same hieroglyph in two styles:

国 (old) 国 (new) kuni, koku (country, region)

号 (old) 号 (new) go (number, name, be called)

变 (old) 変 (new) hen, ka(wara)(change, vary)

Old style Japanese characters were used until after World War II and are, for the most part, the same as traditional Chinese characters. In 1946, the Japanese government legislated for a new style of simplified characters in the Toyo Kanji Jitai Hyo (当用汉字字体表) list.

Some of the new characters coincided with the simplified Chinese characters that are used today in the PRC. As a result of the PRC's writing reform, a number of new characters were borrowed from cursive forms (略字, ryakuji), which were used in handwritten texts. However, in certain contexts, the use of old (correct) forms of some characters (正字, Seiji) was also allowed. There are also even more simplified versions of writing hieroglyphs, but their scope of use is limited to private correspondence.

In theory, any Chinese character can be used in Japanese text, but in practice, many Chinese characters are not used in Japanese. Daikanwa jiten (大汉和辞典) - one of the largest dictionaries of hieroglyphs - contains about 50 thousand characters, but most of them are rarely found in Japanese texts.

Reading hieroglyphs

Depending on how the hieroglyph entered the Japanese language, it can be used to write one or different words, and even more often morphemes. From the reader's point of view, this means that hieroglyphs have one or more readings. The choice of reading a hieroglyph depends on the context, content and communication with other characters, and sometimes on the position in the sentence. The reading is divided into two: “Chinese-Japanese” (音読み) and “Japanese” (訓読み).

Onyomi

Onyomi (音読み - phonetic pronunciation) is a Sino-Japanese pronunciation or Japanese interpretation of the Chinese pronunciation of the character. Some characters have multiple onyomi because they were borrowed from China several times, at different times and from different areas. Kokuji, or the characters that the Japanese themselves invented, usually do not have onyomi, although there are exceptions. For example, in the character 働 “to work” is kunyomi (hataraku), but there is also onyomi, but in the character 腺 “gland” (breast, thyroid, etc.) is only onyomi.

Kunyomi

Kunyomi (訓読み) is a Japanese reading, which is based on the pronunciation of native Japanese words (大和言葉, Yamato Kotoba - “Yamato words”), to which Chinese characters were selected according to their meaning. In other words, kunyomi is the Japanese translation of the Chinese character. Several hieroglyphs may contain several kunyomi at once, or there may not be any at all.

Other readings

There are many combinations of hieroglyphs, for the pronunciation of the components of which both onyomi and kunyomi are used. Such words are called "zubako" (重箱 - "loaded chest") or "yuto" (汤桶 - "barrel of boiling water"). These two terms themselves are autological: the first character in the word “zubako” is read as onyomi, and the second as kunyomi. In the word “yuto” it’s the other way around. Other examples of such mixed readings: 金色 kiniro - “golden”, 空手道 karatedo - “karate”.

Some kanji have a little-known reading - nanori (名乗り - "name name"), which is usually used when pronouncing personal names. As a rule, they are close in sound to kunyomi. Toponyms also sometimes use nanori, or even readings that are not found anywhere else.

Gikun (义训) - reading messages of hieroglyphs that are not directly related to the kunyomi or onyomi of individual characters, but related to the content of the entire hieroglyphic combination. For example, the combination 一 寸 can be read as “issun” (that is, “one sun”), but in reality this indivisible combination is read as “tjotto” (“a little”). Gikun is often found in Japanese surnames.

The use of ateji to write borrowed words led to the emergence of new meanings in hieroglyphs, as well as messages that were unusual in reading. For example, the obsolete message 亜细亜 aji was previously used to write hieroglyphically for a part of the world - Asia. Today katakana is used to write this word, but the sign 亜 has acquired a different meaning - “Asia”, in such combinations as “TOA” 东亜 (“East Asia”).

From the obsolete hieroglyphic combination 亜米利加 (america - “America”), a second character was taken, from which the neologism 米国 (beikoku) arose, which can literally be translated as “rice country,” although in reality this combination means the United States.

Selecting options

Words for similar concepts such as "east" (东), "north" (北) and "northeast" (东北) can have completely different pronunciations: Higashi and kita are the kunyomi readings and are used for the first two characters, while while “northeast” will be read in Onyomi - Tohoku. Choosing the correct character reading is one of the most difficult aspects of learning in Japanese.

As a rule, when reading combinations of hieroglyphs, onyomi is chosen. Such messages are called Japanese jukugo 熟语. For example, the combination 学校 (Gakko, "school"), 情报 (joho, "information") and 新干线 (Shinkansen) are read according to exactly this pattern.

The character, which is located separately from other characters and surrounded by Kana, is usually read using kunyomi. This applies to nouns as well as conjugated verbs and adjectives. For example, 月 (tsuki, month), 新しい (atarashi, "new"), 情け (nasake, "pity"), 赤い (akai, red), 見る (mere, "look") - in all these cases kunyomi is used.

These two basic pattern rules have many exceptions; kunyomi can also form compounds, although these are less common than the message with onyomi. Examples include 手纸 (tagami, “letter”), 日伞 (Higashi, “sun umbrella”), or the famous phrase 神风 (kamikaze, “divine wind”). Such messages may also be accompanied by an okurigana. For example, 歌い手 (utaite, "singer") or 折り紙 (origami). However, some of these combinations can be written without it - for example, 折纸 (origami).

In addition, some characters that stand alone in the text can also be read as onyomi: 爱 (ai “love”), 禅 (zen), 点 (ten “mark”). Most of these characters simply do not have kunyomi, which eliminates the possibility of error.

In general, the situation with the reading of onyomi is quite complicated, since many signs have several such readings. For comparison - 先生 (sensei, “teacher”) and 一生 (issyo, “all life”).

In Japanese, there are homographs that can be read differently depending on the meaning, as in Russian "zamok" and "castle". For example, the combination 上手 can be read in three ways: Uwat (“upper part, superiority”) or kami (“upper part, upper course”), jozu (“skillful”). Additionally, the combination 上手い can be read as Umai (“skillful”).

Some well-known place names, including Tokyo (东京) and Japan (日本, nihon or sometimes nippon) are read with onyomi, although most Japanese place names are read with kunyomi (for example, 大阪 Osaka, 青森 Aomori, 広島 Hiroshima). Surnames and given names are also usually read using kunyomi. For example, 山田 - Yamada, 田中 - Tanaka, 铃木 - Suzuki. However, sometimes there are names that mix kunyomi, onyomi and nanori. You can read them only with certain experience (for example, 大海 - Daikai (on-kun), 夏美 - Natsumi (kun-on)).

Phonetic clues

To avoid inaccuracies, along with hieroglyphs in texts, sometimes there are phonetic clues in the form of hiragana, which are typed with a small point “agate” above the hieroglyphs (the so-called furigana) or in one line with them (the so-called kumimoji). This is often done in texts for children learning Japanese and in manga. furigana is sometimes used in newspapers for rare or unusual readings, and for kanji not included in the list of major kanji.

Number of hieroglyphs

The total number of existing hieroglyphs is difficult to determine. The Japanese dictionary Daikanwa jiten contains about 50 thousand characters, while more complete modern Chinese dictionaries contain more than 80 thousand characters. Most of these characters are not used either in modern Japan or in modern China. In order to understand most Japanese texts, it is enough to know about 3 thousand characters.

Spelling reforms

After World War II, beginning in early 1946, the Japanese government began developing spelling reforms. Some characters received simplified spellings called shinjitai (新字体). The number of characters used was reduced, and lists of hieroglyphs required for study at school were approved. Variant forms and rare characters were officially declared undesirable for use. The main goal of the reforms was to unify the school curriculum for the study of hieroglyphs and reduce the number of hieroglyphic signs that were used in literature and the media. These reforms were advisory in nature. Many hieroglyphs not included in the lists are still known and often used.

Kyoiku kanji (教育汉字)

Kyoiku Kanji (教育汉字, "educational characters") - a list of 1006 kanji that Japanese children learn in elementary school (6 years of schooling). This list was first established in early 1946 and contained only 881 characters. In 1981 it was increased to the current number. This list is divided by year of study. Its full name is "Gakunenbetsu Kanji" (学年别汉字配当表, "Chart of characters by year of study")

Jyoyo Kanji

Jyoyo Kanji (常用汉字, "characters of constant use") - the list consists of 1945 characters, which includes the "Kyok Kanji" for elementary school and 939 characters for middle school (3 years of study). Characters not included in this list are usually accompanied by furigana. The list was updated in early 1981, thereby replacing the old 1850 characters "Toyo Kanji" (当用汉字), which was introduced in early 1946.

Jimmeyo kanji (人名用汉字)

Jinmeyo Kanji (人名用汉字, “hieroglyphs for human names”) - the list consists of 2928 characters, 1945 characters which completely copy the list of “Jyoyo Kanji”, and 983 characters are used to write names and place names. In Japan, most parents try to give their children rare names that include very rare characters. To facilitate the work of registration and other services that do not have the necessary technical means for typing rare characters, in 1981 the “Jinmeyo Kanji” list was approved, according to which names of newborns could only be given with characters from the list, or hirigana or katakana characters. This list is regularly updated with new hieroglyphs, and the widespread introduction of computers that support Unicode has led to the fact that the Japanese government is preparing to add from 500 to 1000 new hieroglyphs to this list in the near future.

Gaiji (外字)

Gaiji (外字, "external characters") are characters that are not represented in existing Japanese character sets. These include variant or obsolete forms of hieroglyphs that are needed for reference books and references, as well as non-hieroglyphic symbols.

Gaiji can be either user or system. In both cases, problems arise when exchanging data, this is because the code tables used for gaiji depend on the computer and operating system.

Nominally, the use of gaiji is prohibited by JIS X 0208-1997 and JIS X 0213-2000, since they occupy code slots reserved for gaiji. However, gaiji continue to be used, for example in the i-mode system, where they are used for drawing signs. Unicode allows gaiji to be encoded in a private area.

Classification of hieroglyphs

The Buddhist thinker Xu Shen (许慎), in his work “Interpretation of Texts and Analysis of Signs” (说文解字), divided Chinese characters into “six writings” (六书, Japanese rikusho), that is, six categories. This traditional classification is still in use, but it is difficult to correlate with modern lexicography - the boundaries of the categories are quite blurred and one hieroglyph can belong to several of them at once. The first four categories relate to the structural structure of the hieroglyph, and the remaining two categories to its use.

Pictogram writing "seki moji" (象形文字)

The hieroglyphs “seki moji” (象形文字) represent a schematic image of the depicted object. For example, 木 - tree or 日 - sun, etc. The original drawings differ significantly from modern forms, so it is quite difficult to decipher these hieroglyphs and their meaning by their appearance. With printed font characters, the situation is much simpler; they sometimes retain the shape of the original design. These kinds of hieroglyphs are called pictographic or seki -象形, the Japanese word for Egyptian pictographic writing. There are quite a few signs of this kind among modern hieroglyphs.

Ideogram letter "Shizu moji" (指事文字)

Shizu moji (指事文字, "pointers") is a type of ideogram or symbolic writing. Hieroglyphs in this category tend to be simple in form and reflect abstract concepts of direction or number. For example, the sign 上 means “above” or “top”, and 下 means “under” or “bottom”. Among modern hieroglyphs, such signs are rare.

Ideogram letter "kayi moji" (会意文字)

The hieroglyphs "kayi moji" are called "folded ideograms". Typically, signs are a combination of a number of pictograms that reflect a common meaning. For example, kokuji 峠 (toge, "mountain pass") consists of the characters 山 (mountain), 上 (top), and 下 (bottom). Another example is that the character 休 (meat "rest") consists of a modified character 人 (person) and 木 (tree). This category is also not numerous.

Phonetic-semantic letter “moji cases” (形声文字)

Moji case hieroglyphs are called “phonetic-semantic” or “phonetic-ideographic” symbols. This is the largest category among modern hieroglyphs (up to 90% of their total number). They usually consist of two components, one of which is responsible for the pronunciation of the hieroglyph, and the other for the content or semantics. The pronunciation comes from ascending Chinese characters. This trace is often noticeable in the modern Japanese reading of onyomi. It is worth noting that the semantic component and its content may have changed over the century since its introduction into Japanese or Chinese. Accordingly, mistakes often occur when, instead of a phonetic-semantic combination in a hieroglyph, they try to see only a folded ideogram. However, Vidkada - the semantics of the hieroglyph in general is an even bigger mistake.

Derived letter "tent moji" (転注文字)

This group includes “derivative” or “mutually explanatory” hieroglyphs. This category is the most difficult of all, because it does not have a clear definition. This includes signs whose content and application have been expanded. For example, the character 楽 means “music” or “pleasure.” In Chinese, depending on the meaning, it is pronounced differently. This is also reflected in the Japanese language, where this sign has different onyomi - hook “music” and raka “pleasure”.

Borrowed letter "kashaku moji" (仮借文字)

This category of “kashaku moji” is called “phonetically borrowed characters.” For example, the character 来 in ancient Chinese was the symbol for wheat. Its pronunciation was a homophone of the word "parish", so the hieroglyph began to be used to write this word, without adding a new meaningful element. However, some researchers note that phonetic borrowings occurred as a result of following ideologemes. So the same sign 来 evolved from “wheat” to “arrival”, through the meaning of “ripening of the crop” or “arrival of the harvest”.

Auxiliary signs

The repeat character (々) in Japanese text means repeating the previous character. So, instead of writing two characters in a row (for example, 时时 tokidoki, “sometimes” or 色色 iroiro, “miscellaneous”), the second character is replaced with a repetition sign and pronounced in the same way as a full-fledged character (时々, 色々). The repeat sign can be used in proper names and place names, such as the Japanese surname Sasaki (佐々木). The repeat sign is a simplified spelling of the character 同.

Another auxiliary character that is often used for writing is the sign ヶ (a reduced katakana sign "ke"). It is pronounced "ka" when used to indicate quantity (such as in the combination 六ヶ月 rok ka getsu, "six months") or as "ga" in place names, such as in Kanegasaki (金ヶ崎). This symbol is a simplified representation of the character 箇.

Dictionaries

To find the desired hieroglyph in the dictionary, you need to know its key and the number of risks. A Chinese character can be broken down into its simplest components called keys (less commonly, “radicals”). If there are many keys in a hieroglyph, one main one is taken (it is determined according to special rules), after which the desired hieroglyph is searched in the key section by the number of risks. For example, the character mother (妈) must be looked for in the key section (女), which is written with three lines, among characters consisting of 13 lines.

Modern Japanese uses 214 classical keys. In electronic dictionaries you can search not only by the main key, but by all possible components of the hieroglyph, the number of strokes or reading.

Tests for knowledge of hieroglyphs in Japan

The main test for knowledge of kanji in Japan is the Kanji Kent Test (日本汉字能力検定试験, Nihon Kanji Noryoku Kent Shiken). It tests abilities in reading, translating and writing hieroglyphs. The test is administered by the Japanese government and serves to test knowledge in schools and universities in Japan. Contains 10 main levels. The most difficult of them tests knowledge of 6000 characters.

For foreigners, there is a simplified Nihongi Noryoku Shiken Test (日本语能力试験, JLPT). It contains 4 levels, the most difficult of which tests knowledge of 1926 hieroglyphs.