The history of Japan is vast and multifaceted. Today we will talk about four great families who at one time had enormous influence in the Land of the Rising Sun. They were the real arbiters of destinies, of which a lot of evidence has been preserved.

By the way, have you ever thought about who your ancestors were? Finding out your ancestry is now easier than ever. You just need to set this goal for yourself and familiarize yourself with the archival documentation or order a detailed pedigree from a company specializing in this type of service.

But let's return to the four families that controlled Japan, looking at each in more detail.

Minamoto clan

Minamoto or, as they were also called, Genji, is a clan whose first representatives were the children of the emperor. However, fate decreed that they were denied the status of princes, as a result of which the imperial descendants turned into ordinary subjects.

Initially, the Minamoto clan was an aristocratic family whose opinion could not be ignored. But over time they were reborn as samurai. This is due to the fact that the family regularly carried out military orders from the capital’s government.

Minamoto is the largest of the ancient clans of Japan. From him comes 21 branches of direct descendants.

Rod Tyra

The history of this clan begins with Prince Katsurawara, who had several illegitimate children. Their descendants eventually formed this family.

The same can be said about Taira as about Minamoto. It is not surprising that these two families waged a fierce struggle among themselves for influence. Its result was the battle in Dannoura Bay, where the Tyra suffered a crushing defeat, after which the clan quickly fell into decline.

Tachibana clan

The Tachibana are the descendants of Prince Naniwa-o. Interestingly, there is a samurai clan of the same name, which has nothing to do with this family.

Like all great families, the Tachibana craved power. And they decided to focus on control over court politics, being remembered for the fact that they did not shy away from any of the methods of fighting competitors. Often violent methods were used, and sometimes it came to global conflicts.

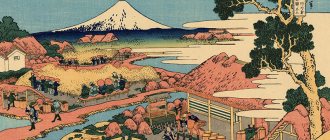

Japan - Fujiwara culture (900-1199)

The name Fujiwara means "wisteria field". It was the place name of one of the first capitals, from 694 to 710, before the government moved to Nara. In 699, Emperor Tenji allowed the powerful Nakatomi family to adopt this poetic name as a patronym in recognition of their many services.

The Nakatomi, who thus became the Fujiwara, continued to grow in strength, created sophisticated and grandiose alliances, and lived in the same era with the state - to such an extent that today the very expression “Fujiwara culture”, having become commonplace, is associated with the splendor of some idealized Middle Ages.

In fact, the Fujiwara, a restless and branched family, ultimately from the 10th century. until the end of the 12th century. secured the main positions in the state - for example, from 967 to 1068. the position of regent under the emperor was passed from father to son: they deliberately sought to appoint a child as sovereign, and then, when he grew up, forced him to abdicate. Today, as in the past, however, the vast majority of people have forgotten the mafia-like features of this system, and its charm remains as strong as ever: it is enough to say “Fujiwara culture” to bewitch listeners, as if this expression had the properties of a magic spell.

The great merit of the Fujiwara was that they personified the deliverance from the Chinese models, which to such an extent determined all life until the end of the 8th century. This does not mean that Chinese culture has faded away - just remember Saicho and Kukai: the roots of everything associated with Buddhism, for example, stretched from the rich religious life of Tang era China. But the Japanese had so internalized the continental elements that they perceived them as inherent in their own identity and no longer noticed their external origin.

Finally, in people's imaginations, the Fujiwara invariably come to life in the images of original and bright personalities, who, by chance - this was an additional bonus of luck - at fateful moments were generated by a certain Eurasian fantasy, mainly enchanting and frightening.

Let us return once again to the thousandth year according to the Christian chronology: Fujiwara no Mitinaga (?—1027) lived in Japan at that time, so omnipotent - so much so that by the end of this century (c. 1092) writers will talk about his splendor in “The Tale of flourishing" (Eiga monogatari), which will soon inspire artists as well.

He was a clever man, greatly helped by the brevity of human life—wasn’t his rise to prominence in 995 due to the premature deaths of his two older brothers? Trying to irritate people and gods, he carefully refused the tempting title of great chancellor, which the sovereign offered him; but, since he was lucky enough to have many sons and daughters (twelve - six sons and six daughters - from two wives), he managed to successfully marry them, becoming several times the father-in-law, and then the grandfather of the emperors. Therefore, when he died in 1027, the Council already consisted only of representatives of the Fujiwara clan. This did not seem to bother anyone: the Japanese never felt the need to create a bureaucracy, theoretically independent of the noble families, such as existed in China. They viewed government positions primarily as honors rightfully due to the most brilliant, to those who managed to gain the favor of the emperor.

Thus, by the middle of the 11th century. The Fujiwara so monopolized warm places and honorable functions that there was little left for other clans. Mitinaga (especially from 1017) also diverted to himself and his family the stream of natural taxes in rice and silk sent by the regional governors; thanks to this, he became the richest man in Japan within a system that functioned as a closed loop, especially since in his place he could control the appointment of governors and make them his clients. However, as in all court families, he sent younger members of the family to the provinces; Thus, nepotism was combined with clientelism in a completely natural way.

This Fujiwara power—or their power over the state—notably contributed to the development of the Japanese political system, which was theoretically copied from the Chinese and involved centralization. But the Fujiwaras, on the contrary, introduced into it a strong imprint of nepotism, quite similar to the ancient clan systems (uji). This is justified, they said, because they govern lands where court officials have no practical ability to exercise power. Having grown up in the regions and returned to the court, the descendants of this family brought a fresh breath there, integrating the provincial way of life into the already old system of the centralized state. Always dexterous, they at the same time did not in any way strive for revolutionary changes, showing full respect to both the glanders and the person of the emperor; their artful policy of marrying off their daughters eventually linked them almost genetically to the line of sovereigns. Therefore, the Fujiwara can be considered the progenitors, biological and political, of the Japanese state of the Middle Ages and modern times: provincial clans rule, the emperor reigns.

Since 1040, the restoration and then the reform of the system of estates created in the middle of the 8th century significantly accelerated this process.

This refers to territories, the management of which - and, accordingly, tax revenues from them - the court government left to families, as a rule, for a very long time physically or morally connected with the imperial power. The government did not lose interest in these territories, but by allowing them to be turned into soep, estates managed by someone else, it relieved itself of responsibility for them. Indeed, demographic development—Japan probably then had seven to eight million people—made the periodic redistribution of land increasingly difficult. And then, the increase in the number of mouths and labor that needed to be occupied implied the development of new territories. As usual, the rulers of the regions were not slow to get the government to recognize these territories where virgin soil was raised beyond them, citing the fact that they contributed to the spread of the administrative framework and regulations that were adopted in the capital and in areas directly controlled by the government. For subordinates, the estate had a completely human scale - regional, and its inhabitants learned to respect land ownership, income, taxes, without trying to find out who was going to the last one. So this system, originally conceived as a reasonable form of delegating a certain power to the agents of the central government, concentrated in their hands, ultimately became a powerful factor of geographical, political and even social fragmentation.

Fujiwara family

This is the only clan whose founder was not a descendant of the emperor. At the origins of the Fujiwara family was Nakatomi no Kamako, a politician of the Asuka period.

The progenitor of the clan is known for having managed to organize a conspiracy against a ruler he disliked, but at the same time almost omnipotent. Symbolically, it was Fujiwara who subsequently occupied leading roles in Japanese politics. Their influence on the country was expressed in lobbying for a variety of initiatives, including starting/ending wars.

When the Meiji Restoration began, all Japanese were instructed to take surnames. And many decided to include in their composition the hieroglyph, which was the first kanji for the name of the Fujiwara clan. Thus, it contains the most popular surname in the Land of the Rising Sun - Sato. This once again emphasizes the greatness of this family.

<Kojima is a genius

Five Iconic Japanese Actresses of the Golden Age>

Excerpt characterizing Fujiwara (genus)

Since Prince Andrei had not seen him, Kutuzov had grown even fatter, flabby, and swollen with fat. But the familiar white eye, and the wound, and the expression of fatigue in his face and figure were the same. He was dressed in a uniform frock coat (a whip hung on a thin belt over his shoulder) and a white cavalry guard cap. He, heavily blurring and swaying, sat on his cheerful horse. “Whew... whew... whew...” he whistled barely audibly as he drove into the yard. His face expressed the joy of calming a man intending to rest after the mission. He took his left leg out of the stirrup, falling with his whole body and wincing from the effort, he lifted it with difficulty onto the saddle, leaned his elbow on his knee, grunted and went down into the arms of the Cossacks and adjutants who were supporting him. He recovered, looked around with his narrowed eyes and, looking at Prince Andrei, apparently not recognizing him, walked with his diving gait towards the porch. “Whew... whew... whew,” he whistled and again looked back at Prince Andrei. The impression of Prince Andrei's face only after a few seconds (as often happens with old people) became associated with the memory of his personality. “Ah, hello, prince, hello, darling, let’s go...” he said tiredly, looking around, and heavily entered the porch, creaking under his weight. He unbuttoned and sat down on a bench on the porch. - Well, what about father? “Yesterday I received news of his death,” Prince Andrei said briefly. Kutuzov looked at Prince Andrei with frightened, open eyes, then took off his cap and crossed himself: “The kingdom of heaven to him! May God's will be over us all! He sighed heavily, with all his chest, and was silent. “I loved and respected him and I sympathize with you with all my heart.” He hugged Prince Andrei, pressed him to his fat chest and did not let him go for a long time. When he released him, Prince Andrei saw that Kutuzov’s swollen lips were trembling and there were tears in his eyes. He sighed and grabbed the bench with both hands to stand up. “Come on, let’s come to me and talk,” he said; but at this time Denisov, just as little timid in front of his superiors as he was in front of the enemy, despite the fact that the adjutants at the porch stopped him in angry whispers, boldly, knocking his spurs on the steps, entered the porch. Kutuzov, leaving his hands resting on the bench, looked displeased at Denisov. Denisov, having identified himself, announced that he had to inform his lordship of a matter of great importance for the good of the fatherland. Kutuzov began to look at Denisov with a tired look and with an annoyed gesture, taking his hands and folding them on his stomach, he repeated: “For the good of the fatherland? Well, what is it? Speak." Denisov blushed like a girl (it was so strange to see the color on that mustachioed, old and drunken face), and boldly began to outline his plan for cutting the enemy’s operational line between Smolensk and Vyazma. Denisov lived in these parts and knew the area well. His plan seemed undoubtedly good, especially from the power of conviction that was in his words. Kutuzov looked at his feet and occasionally glanced at the courtyard of the neighboring hut, as if he was expecting something unpleasant from there. From the hut he was looking at, indeed, during Denisov’s speech, a general appeared with a briefcase under his arm. - What? – Kutuzov said in the middle of Denisov’s presentation. - Ready? “Ready, your lordship,” said the general. Kutuzov shook his head, as if saying: “How can one person manage all this,” and continued to listen to Denisov. “I give my honest, noble word to the Hussian officer,” said Denisov, “that I am aware of Napoleon’s message.”