Muromachi period (Ashikaga shogunate) (1333 - 1573)

Muromachi Period (Muromachi Jidai, 1333-1573 CE)

Emperor Go-Daigo was able to restore imperial power in Kyoto and overthrow the Kamakura Bakufu in 1333. However, the revival of the old imperial offices at the Kemmu (1334) did not last long, as the old system of government was outdated and ineffective, and incompetent officials were unable to gain the support of powerful landowners. The three-year period of imperial rule in Japanese history between the Kamakura period and the Muromachi period from 1333 to 1336. The Kemmu Restoration was the last time the Emperor of Japan had any power until the Meiji Restoration in 1868.

Ashikaga Takauji, who had once fought for the emperor, now defied the imperial court and succeeded in capturing Kyoto in 1336. Go-Daigo, fled to Yoshino in southern Kyoto, where he founded the Southern Court. At the same time, another alternative emperor was appointed in Kyoto. This was made possible by the succession dispute that had been raging between the two clans of the imperial family since the death of Emperor Go-Saga in 1272.

In 1338, Takauji appointed himself shogun and established his government in Kyoto. The Muromachi area, where government buildings have been located since 1378, gives the government and the historical period its name.

Portrait from the 14th century AD Japanese Emperor Go-Daigo (b. 1318-1339).

For more than 50 years, there were two imperial courts in Japan: Southern and Northern. They fought each other a lot. The northern court was usually in a more advantageous position; Nevertheless, Southern managed to capture Kyoto several times for short periods of time, which led to the regular destruction of the capital. The southern court finally surrendered in 1392, and the country once again submitted to one emperor.

During the era of Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu (1368 - 1408), Muromachi Bakufu was able to control the central provinces, but gradually lost its influence over the outer regions. Yoshimitsu established good trade relations with Ming China. Domestic production also increased due to improvements in agriculture and the effects of the new inheritance system. These economic changes led to the development of markets, the emergence of several types of cities, and the emergence of new social classes.

Tomoe Gozen (巴御前). Samurai woman

During the 15th and 16th centuries, the influence of the Ashikaga shoguns and the government in Kyoto faded away. The political novices of the Muromachi period were members of landowning, military families (ji-samurai). First cooperating with and then surpassing provincial constables, some of them achieved influence over entire provinces. These new feudal lords became known as daimyo ("great name"). They exercised virtual control over various parts of Japan and fought each other continuously for several decades, during a difficult period of civil wars (Sengoku Jidai "Era of the Warring States"). The most powerful lords were Takeda, Uesugi and Hojo in the East, and Ouchi, Mori and Hosokawa in the West.

In 1542, the first Portuguese traders and Jesuit missionaries arrived in Kyushu and introduced firearms and Christianity to Japan. The Jesuit Francis Xavier undertook a mission to Kyoto in 1549-50. Despite Buddhist opposition, most Western military leaders welcomed Christianity because they were interested in trading with overseas countries mainly for military reasons.

By the mid-16th century, several of the most powerful military leaders were vying for control of the entire country. One of them was Oda Nobunaga. He took the first big steps toward Japanese unification by capturing Kyoto in 1568 and overthrowing the Muromachi Bakufu in 1573.

Despite the political turmoil, the Muromachi period saw significant cultural growth, especially under the influence of Zen Buddhism. The unique Japanese arts of tea ceremony, flower arranging, and Noh drama were developed, and the Shun style of ink painting (sumi) reached its peak. In architecture, simplicity and rigor have become the general rule. Both the Golden Pavilion (Kinkaku-ji) and the Silver Pavilion (Ginkaku-ji) in Kyoto were built during the Muromachi period.

Views: 1,288

Share link:

- Tweet

- Share posts on Tumblr

- Telegram

- More

- by email

- Seal

Liked this:

Like

Similar

Download the large encyclopedia of Japan from A to Z with multimedia:

MUROMACHI is the historical period from 1333 to 1568. Often divided into two subperiods: the Southern and Northern Imperial Dynasties (1336–1392) and the “Era of the Warring States” (1467–1568).

Emperor Go-Daigo's attempt to regain full power in the country in 1333 ended unsuccessfully. There were many reasons for this, both objective and subjective. And among them, betrayal played a significant role. The military leader Ashikaga Takauji, who had once been seduced by the promises of Go-Daigo and marched under his banner against the Hojo clan, whose vassal he was, did not want to remain loyal to the new overlord. In order not to share state power with Go-Daigo, who had considerable political influence, Ashikaga placed his puppet on the throne - the new Emperor Komyo. Go-Daigo, who did not agree with this turn of affairs, did not want to voluntarily renounce the title of tenno and with his closest associates fled from the capital to the south, where he founded his residence in the mountain town of Yoshino (Yamato Province). Thus, in Japan there were immediately two emperors and two imperial courts - the Northern one in Kyoto and the Southern one in Yoshino.

As for real power, it continued to be in the hands of the military. In 1338, Ashikaga Takauji proclaimed himself the new shogun, left Kamakura, which was too ascetic and too far from the capital, and moved his headquarters to Kyoto. His palace was built in the Muromachi quarter of Kyoto, which gave rise to historians subsequently calling the years of the Ashikaga shogunate the Muromachi period (1333–1568).

Despite all the limited power of the imperial courts, a serious struggle ensued between them. Both the northern and southern emperors had many vassals, who very often got involved in armed fights among themselves for the right to influence a particular territory and especially for the taxes collected there. Shogun Ashikaga pretended to remain neutral for some time, but, of course, supported his protege in Kyoto. As a result, the “dual kingdom,” which lasted nearly six decades, ended with some kind of compromise. The opposing emperors agreed that the Chrysanthemum Throne would be occupied in turn by the descendants of Go-Daigo and Komio. But the first in this row was the heir to the Northern Court, which solved the problem. The promises made to the south were simply “forgotten” in the future. However, disputes about the legitimacy of the rights of the heirs of the Northern and Southern courts lasted in Japan with varying success almost until the middle of the twentieth century.

Meanwhile, the deceased Ashikaga Takauji was replaced by his son Yoshiakira, who, in turn, was replaced as shogun by his son Yoshimitsu. The power of the Ashikaga house in the country lasted about 240 years. The Ashikaga shoguns were not as powerful as the leaders of the Kamakura shogunate, and were unable to extend their unconditional influence to all clans.

The shogunate sent its military rulers (shugo) throughout the country. Theoretically, they were representatives of the central government, but in reality, sensing the weakness of the center, they most often gravitated toward separatism, refused to transfer collected taxes to the capital, and recruited their own armies from local samurai. Gradually, entire regions began to emerge from the control of the shoguns. Almost independent autocratic domains were formed locally, headed by princes (daimyo). Other principalities covered the territory of several provinces. It happened that their troops captured the capital and the next daimyo began to rule the country on behalf of the shogun, who gradually turned into a puppet, which, in turn, was a “puppeteer” for the imperial court.

The ineffectiveness of government, the self-interest of officials and daimyos were superimposed on very unfavorable natural situations. Droughts and floods destroyed that part of the harvest that survived the passage and fighting of the samurai squads. One after another, peasant uprisings and food riots broke out in the country. The rebels demanded a reduction in taxes, a change in the hated shugo governors, and even tried to create some semblance of provincial self-government bodies. In the wake of these events, some of the local feudal lords tried to seize power in the province, taking the place of the expelled or killed shugo. These years in Japanese historiography are called gekokujo (the inferior defeat the superior).

Defending themselves from the punitive forces of the shogun and daimyo, the peasants turned their villages into fortified points, erecting tyns and palisades. This example was followed by some cities seeking self-government. Such rights were achieved, in particular, by the cities of Sakai (near Osaka) and Hakata (in the north of Kyushu).

Internal troubles became particularly acute in the second half of the 15th century. The incompetence of the authorities has reached its limit. Famine, drought, floods, typhoons, and epidemics devastated the country. If during the Kamakura shogunate the rulers of the country, while remaining large landowners, were at least by hearsay familiar with agricultural production and its problems, then the pampered and corrupted Ashikaga shoguns could not do anything to oppose the rampant elements, disease, and hunger. They plunged headlong into intrigues around the succession to the throne and the distribution of court sinecures.

The quarrel over key posts in the shogunate also gave rise to the so-called turmoil of the Onin years (named after the years of the emperor’s reign), which lasted 11 years, starting in 1467. Almost 300 thousand people were involved in hostilities. The battles rolled in waves across the entire capital, leaving behind ruins and ashes. Then, from dilapidated Kyoto, the struggle spread to the provinces, drawing local daimyo and their squads into a military confrontation.

Each of the warring armies sought to win over the emperor and shogun to its side. But neither one nor the other found the strength, courage and determination to stop the bloody quarrel of the raging vassals. Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa preferred aesthetic pleasures to the vanity of government in a villa built for him at the foot of Mount Higashiyama, east of Kyoto. While the country was seething, figuring out who stood where in the “table of ranks,” Yoshimasa organized exquisite tea ceremonies, Noh theater performances, and exhibitions of art collections for those close to him. A group of artists, an entire cultural complex, now known as the “Higashiyama culture,” developed around Yoshimasa. Its integral parts were park art, Noh drama, ikebana, tea ceremony, landscape painting, and poetry.

Meanwhile, exhausted by the long and inconclusive war, the participants in the Onin Troubles were forced to make peace. But peace never came to Japan. Armed strife and civil strife continued for about another century. Powerful daimyo seized the estates of weaker ones. Vassals rose up in arms against their overlords. This time is called Sengoku Jidai (“Era of the Warring States”) in Japanese history.

If we compare the historical calendars of Japan and Europe, then this period is better known in the world as the time of great geographical discoveries. While Japan was establishing trade relations with its closest neighbors - China, Korea, and the countries of Southeast Asia, while its pirates were causing terror in the area, Vasco da Gama paved the sea route to India. And then in 1543, a storm washed a ship of Portuguese adventurers onto the small island of Tanegashima off the southern coast of Kyushu. This is how Europeans first set foot on Japanese territory.

But the events of those times are famous not only for the priority of the Portuguese “discovery of Japan”. There were several muskets in the holds of the galleon that ran aground off the Japanese coast. The first firearms were brought to Japan even earlier - from China. However, the Japanese who met him perceived him rather as a curiosity. But the Portuguese, who wanted to capture the imagination of the aborigines, managed to present the “product of European genius” properly, without skimping, they conducted demonstration shooting, explained to the interested samurai the principle of operation of firearms and the method of handling them.

Japanese warriors quickly realized what advantages Portuguese weapons could give them in constant military clashes with their neighbors. Dozens of Japanese craftsmen were seated at workbenches to mass produce muskets. In addition, shipments of weapons began to arrive with enviable regularity from European traders, who exchanged them in Japan for gold, silver, copper, and slaves. Within ten years, the daimyo's troops from Kyushu and surrounding areas had strong units of musket shooters, which allowed them to easily defeat opponents who used traditional bows and arrows. This changed Japan's entire military tactics in a most revolutionary way. Individual battles of samurai, into which any battle inevitably broke up, gave way to much more effective collective actions of foot shooters (ashigaru). From Kyushu, muskets called "Tanegashima" began to spread throughout Japan.

And in 1549, the Spanish Jesuit preacher Francis Xavier arrived in the Land of the Rising Sun. He, and then his followers, began to spread Catholicism in Western Japan. The matter was not limited to sermons about the life of Christ and his apostles. The missionaries built hospitals and schools, printed their religious literature, and shared with local residents the basics of European knowledge in astronomy, geography, and medicine. Gradually, Catholic missions began to seize the wealth of Buddhist monasteries. Local daimyo turned a blind eye to this process. Moreover, interested in acquiring European weapons, they themselves converted to Catholicism and encouraged their vassals to do so. At the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries. Every fiftieth Japanese professed Christianity. (It is noteworthy that in modern Japan, where freedom of conscience is guaranteed, the percentage of Catholic believers is two times lower.)

The turn of the 15th and 16th centuries. became an important milestone in the history of Europe and Japan, thousands of kilometers apart. Both there and here the process of overcoming feudal fragmentation began, attempts were made to unite states under strong authoritarian rule. For Japan, this trend is associated primarily with the name of daimyo Oda Nobunaga.

Nobunaga's possessions, relatively small, were located in the province of Owari in the central part of the island of Honshu near present-day Nagoya. Oda Nobunaga was perhaps the first Japanese to appreciate the importance of firearms. His ashigaru troops, armed with muskets, easily achieved an advantage in battles with squads of neighboring principalities. In 1560, Nobunaga defeated the troops of Imagawa Yoshimoto, the daimyo of the rich province of Mikawa (now part of Aichi Prefecture). The victory inspired the commander to new campaigns. Smashing the armies of his neighbors, seizing their territories, subjugating strong Buddhist monasteries to his will, Nobunaga quickly united almost half of Japan under his leadership.

However, Nobunaga also had powerful opponents. Among them, the Buddhist monastery of Ishiyama Honganji especially stood out for its stubborn resistance. His monks and parishioners more than once rebelled against the power of the Nobunaga clan imposed on them. During one of these performances in 1570, they killed Nobunaga's brother. The enraged Oda twice tried to attack Nagashima, the center of the rebels, and was unsuccessful. Only a long sea and land siege broke resistance. Half of the defenders died of starvation, all the rest were executed by Nobunaga's soldiers. During the punitive expedition, about 20 thousand people died. Nobunaga ruthlessly dealt with his opponents, believing that only a strong hand and strong will could unite Japan.

Oda Nobunaga was considered a consistent supporter of the shogunate. It was he who in 1568 brought to power Yoshiaki Ashikaga, the fifteenth (and last!) Shogun of this dynasty. But in 1573, the same Nobunaga deprived Yoshiaki of his shogunal powers. The Muromachi period is over.

History of the Japanese sword 5

The Ashikaga shogunate , whose headquarters was located in the village of Muromachi , by the time of Yoshimitsu's reign was left without opponents for power. But a new situation arose - the provinces were constantly in conflict. After the assassination of the sixth shogun of the family, Ashikaga Yoshinori, in 1461, the country again split into two camps. The eastern camp was headed by the Hosokawa clan, and the western camp by the Yamana clan. The conflict exploded in 1467 with the outbreak of the Onin War, a time of turmoil in the Sengoku-jidai (era of the Warring States) . There was no central authority, the state was split into numerous principalities, and the country became impoverished. Many ancient families sank into oblivion, but large feudal lords Takeda, Mori, and Uesugi appeared on the scene.

These people pursued progressive economic policies and allowed artisans to settle around their castles. And by the end of the 16th century there were 83 castle towns in Japan. The enrichment of the princes allowed them to strengthen both their castles and their armies.

The strengthening of some daimyo, the strengthening of their economy and military strength by the second half of the 16th century put Japan in danger of a new redistribution of territory. Previous lessons spoke of the need for central authority, but no one wanted to obey. A leader was needed, Oda Nobunaga . The son of a small feudal lord from the province of Owari. Having become the head of the clan in 1551, seventeen-year-old Oda began to seize neighboring lands. Being a talented military commander, an intelligent and fearless leader, he soon subjugated most of the country and was even able to influence the Ashikaga shogunate. Moreover, he overthrew the shogun Ashikaga Yoshiaka in 1573. This ended the Ashikaga period of power, the Muromachi period.

The shoguns of the Ashikaga clan put a lot of effort into developing culture. This was a period of ennobling crafts with Zen philosophy.

The tenets of Zen strengthened the institution of the sword and crystallized its moral and spiritual status. During the Muromachi era, the sword became especially revered. This time is characterized by a story when, during the siege of a castle, its owner asked the enemy in a letter to suspend the siege in order to save a collection of swords from destruction in a fire, the siege was suspended, the swords were handed over to the besiegers, and only after that the battle resumed. There was no such attitude towards the sword in previous times.

The Ashikaga sought to improve relations with China and therefore used Japanese swords, which were highly revered on the mainland, as gifts.

During the reign of Genko and Kamu, yari , and after the years of Onin, yari became increasingly widespread.

During constant wars, the yari was highly valued as an important type of weapon. It is interesting that the spread of yari with a double-edged straight blade is interconnected with the appearance of firearms. The gun radically changed battle tactics. At first, the roar of shots frightened the cavalry. Because of this, the system broke down and panic was sown. And, as a result, the arquebusiers began to fire deliberately at the horses. Tactics became more complicated, and the need arose to train soldiers to fight in a crowded environment. There was nothing better than a yari spear in such conditions. It was enough to hit the enemy's armor with a spear to knock him down. Therefore, even a hastily recruited army, armed with long spears, was a serious force. The end of the Muromachi period was marked by the growth in the role of spears and infantry.

To increase their status, the Ashikaga clan declared its succession to the Kamakura shogunate many times. This even manifested itself in the fashion for swords. Narrow blades were making a comeback, with samurai preferring early Kamakura style tachi , but with a curved blade in the upper half. This also affected the fighting technique. With the tachi suspended from the belt - drawing the sword, swinging, striking - three movements, now the sword began to be worn with the cutting edge up, inserting the sheath into the belt. They drew the sword with an up-and-forward movement, immediately swinging it and immediately delivering a blow. The new swords were called uchigatana. They were equipped with a kurigata with a hole for a strap and tsuba, which was not previously available. sakizori blade made it possible to expose the uchigatana in one natural movement. A blow, a deadly blow, could be delivered from any position, even the most relaxed one. Later, a similar technique became the art of yai-jutsu , where the sakizori was extremely important.

These advantages ensured uchigatana's popularity among samurai and nobles. This also increased the quality of uchigatan .

But this does not mean that blacksmiths stopped producing tati . Many blacksmith schools remained faithful to traditions and had no problems with sales.

The terminology of swords has also changed. In 1532-1570, swords with a blade length of more than 75 cm began to be called odachi swords . The handle of these odachi was made long with the expectation that the sword placed on the ground would reach the owner’s ear. Uchigatana were divided into two families according to the length of the blade: more than 60 cm - katana , less - wakizashi (accompanying sword). These swords were equipped with tsuba, often carved iron, the handles were covered with same skin and braided with cord. The scabbard was varnished with a black shiny smooth varnish. This style is called Akechi frame - akechi-koshirae . This is a practical, cheap and discreet style, which has ensured great popularity.

During the Muromachi period there was a wide variety of styles. For example, frames in the sayamaki originated from the ancient frames of the tsuzura-sawamaki style (braided with a rattan plant), which was used to braid both the hilt and the sheath. Subsequently, rattan was no longer used, imitating it with carvings. During the Minamoto period, sayamaki were called scabbards braided with cord, but in Muromachi they again became interested in imitation rattan.

During the Muromachi period, the swords of soldiers in battles were mounted in the style of akechi-koshirae , and those of military leaders - itomaki-no-tachi . shirizaya of earlier times has now become mere decoration, losing the symbolism of status or warrior courage.

All this diversity served to separate the art of sword decoration into a separate craft. During this period, hereditary dynasties of sword jewelers appeared. The most famous of them is the Goto dynasty . To this day, her descendants work in Japan. The art of gunsmiths of the Muromachi era evokes controversial thoughts. Despite the improvement of smelting, the assistance of the feudal lords, despite the strengthening of the social and economic status of the blacksmith union, the development of trade, and even despite the demand for swords, the Muromachi period did not produce significant names of blacksmiths.

Before the Sengoku-Jidai era there were still great blacksmiths, but then there were none. It is believed that it was the great demand for weapons that caused the degeneration of blacksmithing. Swords were bought in hundreds, blacksmiths were constantly in a hurry, demanding speedy execution of orders. All this forced us to forget about the high quality of blades of former times, as a result of which many secrets were forgotten, which are being restored to this day. But there was another reason. The long war led to devastation and for many daimyo it became expensive to purchase high-quality blades. A tradition arose of donating swords for certain merits or under certain circumstances, supplementing this gift with horses and certain valuables.

Nevertheless, there were significant names and schools of the Muromachi period. So master Masatsune (1534-1619) from Sagami became the personal blacksmith of the Tokugawa , the future rulers of Nippon. The Gassan school in Dewa was famous, and the blacksmiths of the Bizen province retained their skills. The engravings of swords on blades, which appeared during the Kamakura period, were reincarnated in the Muromachi era into images of Buddhist and Shinto deities, whom samurai revered as protective deities or gods of war.

| Have you read it? Liked? You can also: Add to favorites |

| Stock! Discounts! Competitions! Discount on Bestblades from Haralug Friends! We all love FREE! Well, if not all, then many. Our chief is Harm - that’s for sure! And he loves it, and he loves to give it, this very FREE. Today's freebie... Comments (0) | |

Events[edit]

- 1336: Ashikaga Takauji captures Kyoto and forces Emperor Daigo II to move to the southern court (Yoshino, south of Kyoto).

- 1338: Ashikaga Takauji declares himself shogun

, moves his capital to the Muromachi district of Kyoto, and supports the northern court. - 1392: The Southern Court surrenders to Shogun

Ashikaga Yoshimitsu and the empire is reunited. - 1397: Kinkaku-ji built by Ashikaga Yoshimitsu.

Ryoan-ji rock garden

- 1450: Hosokawa Katsumoto built Ryoan-ji.

- 1457: Edo is installed

- 1467: The Onin War split between feudal lords ( daimyo

). - 1489: Ginkaku-ji built by Ashikaga Yoshimasa.

- 1543: Shipwrecked Portuguese introduce firearms

- 1546: Hōjō Ujiyasu, who won the Battle of Kawagoya, becomes ruler of the Kanto region.

- 1549: Catholic missionary Francis Xavier arrives in Japan.

- 1555: Mōri Motonari, who won the Battle of Miyajima, becomes ruler of the Chūgoku region.

- 1560: Battle of Okehazama

- 1568: Daimyo

Oda Nobunaga enters Kyoto and ends the civil war [7] - 1570: Founding of the Archbishopric of Edo and ordination of the first Japanese Jesuits.

- 1570: Battle of Anegawa

- 1573: Oda Nobunaga overthrows Bakufu

and expands his control over all of Japan [7]: 281

Muromachi era

| History of Japan |

(VI century - 1185)

(1185—1573)

(1333—1336) (including Nambokucho and Sengoku) (1336–1573) (1573—1868)

(1868—1945)

(since 1945)

|

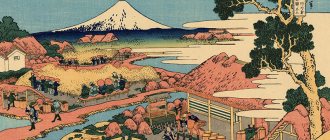

One of the main attractions of the Muromachi era is Kinkaku-ji ( Kyoto

)

Muromachi period

[1],

Muromachi-jidai

[2] (Japanese 室町時代

muromachi jidai

, 1336-1573) - a period in the history of Japan during which the shogun's headquarters was in Muromachi.

In 1334, with the support of Buddhist monasteries and the military led by Ashikaga Takauji, Emperor Go-Daigo briefly restored imperial rule. However, already in 1336, Ashikaga enthroned another convenient emperor to the throne in Kyoto, who was ready to bestow on him the title of shogun. Having received the title of shogun in 1338, Ashikaga Takauji founded a military headquarters in the Muromachi region near Kyoto. In contrast to the Kamakura shogunate, within which small-scale fief landownership predominated, during the Muromachi period large feudal estates and feudal principalities began to predominate, uniting several provinces that did not always recognize the authority of Ashikaga. As a result, centrifugal tendencies and internecine conflicts intensified. Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu (1368–1408) still tried to control the central lands, but lost his influence in the remaining provinces.

In the 15th-16th centuries, the Ashikaga shoguns almost completely lost influence on events. In the 15th-16th centuries, the clans of large landowners “ji-samurai”, having united, quickly surpassed the strength of the previous feudal lords and, ignoring the will of the shoguns, spread their influence over entire provinces and for several decades continuously waged internecine struggle among themselves, which was called “ period of warring principalities", Sengoku-jidai in 1467-1568.

In an atmosphere of deep feudal fragmentation, the virtual absence of central power and the economic crisis in the middle of the 16th century, the question of the political unification of the country, in which large feudal lords were primarily interested, arose. One of them was Oda Nobunaga, who in 1560-1582 managed to win a series of victories over many large feudal lords and Buddhist monasteries and seize their lands. In 1568, Oda captured the capital. An unsuccessful attempt to appoint his protege as shogun led to the final overthrow of the Ashikaga shogunate (from that time until 1603 there were no shogunates in Japan).

After Oda's death in 1582, the further unification of the country was continued by his comrade-in-arms, the military leader Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who gradually gained power over vast territories. In addition to the military conquests, Toyotomi Hideyoshi carried out a number of important socio-economic transformations (restoration and strengthening of the power of the central government and the state apparatus, reforms in the agricultural sector, a population census, confiscation of weapons from peasants and monks, the creation of the samurai class.

The events that took place since the reforms of 1493 began to be called the Age of the Warring Provinces. Another popular belief is that these events began with the Onin War in 1467.

The following notable events occur during the Muromachi period:

- The poet Yoshimoto Nijo, advisor and prime minister, together with the poet Gusai compose the collection of renga poetry "Tsukuba-shu".

- Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu builds the "Golden Pavilion" of Kinkakuji.

- The Onin War (1467–1477) between the successors of shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa.

- The Portuguese bring muskets to Japan. The proliferation of firearms in Japan begins.

During the Kamakura period (1192-1333), power passed from the aristocrats to warriors - samurai (bushi). In art they begin to appreciate the beauty of the mysterious - yugen. If mono no aware is the charm of things that, with their attractiveness, awaken pleasant sadness, then the beauty of yugen can only be felt in a special state of mind. This is the beauty of the invisible, secret, hidden from view, which takes your breath away. Theater theorist No Zeami (1363-1443) said: “There is something hidden in everything, it is beautiful.”

What are the reasons for the change in aesthetic ideal? Perhaps in the instability of power, which seemed unshakable, in the drama of the 12th century, at the end of which one clan, the Taira, was overthrown by another clan, the Minamoto. In 1192, Minamoto Yeritomo was declared the supreme ruler of Japan. The second estate, the bushi, came to power, whose rule lasted until the mid-19th century. The emperor and court remained in the old capital of Heian (Kyoto), but the cultural center moved to the periphery, to Buddhist monasteries. Buddhism, with its idea of the fragility of earthly existence, was confirmed in life. The enthusiasm of Shinto was replaced by a Buddhist tendency towards contemplation, the search for ways to overcome existence, to achieve complete tranquility - nirvana.

Since we have combined the two periods of Kamakura and Muromachi, this section will examine the features of Japanese culture characteristic of both of these periods, i.e. from 1185 to 1568 Let's try to trace how the yugen style of the Kamakura period was transformed into wabi-sabi of the Muromachi period, how these aesthetic categories manifested themselves in the art of theater, the work of Basho, the ritual of the tea ceremony, poetry, samurai culture and much more...

Poetry anthology "Shinkokinshu"

At the beginning of the Kamakura period, another anthology appeared that surpassed the Heian one in skill - Shinkokinshu (New Kokinshu (1205)). Sadaie was the main compiler of the great anthology. The authors of the anthology saw the meaning of poetry in revealing yugen, the beauty of silence, peace, detachment from the world, from the “I”, burdened with worries, merging with the cosmic “I”.

In "Shinkokinshu" many poems are built on the principle of "honkadori": the poem quotes a line from the poems of another poet, contemporary or predecessor. Japanese poetry has a huge memory, a sense of its continuity. By quoting the line, the poet seems to join the heartfelt feelings of his brother.

Poets expressed the spirit of yugen with the help of yojo (“super-feeling” Wink. As Fujiwara Teika said: “Without yojo there is no poetry.” This difficult-to-translate word is usually interpreted as “emotional response,” “after-feeling, hint, understatement, but all these are separate aspects of yojo. This technique can be compared to the state of magokoro (true heart), the absolute fullness of the heart, which is identical to Emptiness. In this case, words are unnecessary, communication occurs at the level of consonant qi, or, as the Zen masters say, “from heart to heart.” When the soul is enlightened, there is no need for words. Zeami said that the artist is able to convey all the colors and moods of nature, forcing his spirit to become colorless and impervious. His spirit, having turned into nothing, will become capable of embracing all the phenomena of the universe, for then his creative power will become equal to the energy of the universe.

Already the 11th century poet Fujiwara Kinto, discussing the harmony of “heart” and “word”, spoke of yojo as “fullness of the heart” (amari no kokoro). If Nothingness was accepted as a truly existing thing, then, naturally, the basic law of poetry becomes yojo, hint, understatement. According to D.T. Suzuki, the secret of Japanese art lies in the hint. Beauty is revealed to those who complete the unfinished in their imagination.

Yojo involves special technical techniques, the technique of “kugiri” - a pause (lit. “breaking a phrase” to excite the imagination), caesura, which breaks the tanka into two stanzas (a tercet and a couplet), or the technique of taigendome - ending the tanka with an inconjugated part of speech so that continue its sound in the reader’s soul. These techniques were used especially often in the Shinkokinshu anthology.

The statement of the philologist and poetry theorist Fujiwara Sadaie: “The words must be old, but let the heart be new,” gives a lot for understanding the poetry of that era. Sadaie's own poems are marked by exquisite beauty:

How I once caressed the black hair of my beloved! Each, every strand On my lonely bed I go over it in my memory.

The poem is structured in such a way that the memory motif makes it endless...

“In the style of Yugen”

The term Yugen, in contrast to Avare, is of Chinese origin. Yugen comes from yu - foggy, difficult to distinguish; gen - dark, deep. In Japan, the word yugen appears as an independent aesthetic category only in the Heian period, despite its earlier mention in the preface to the Chinese version of Kokinshu.

In the Kamakura era, yugen expresses the impressions and feelings experienced by a person who contemplates the moonlight streaming through the haze of a passing cloud, or when he admires the whirling snowflakes sparkling like silver. Yugen contains something new in this image: a direct indication of involvement in light and sparkle, but a cold, detached light - this is the coolness of Buddhism. Poems that painted such pictures were called “yugen style.” They are characterized by being permeated with sadness.

One of the most accurate definitions of yugen can be recognized by Tanka Fujiwara Toshinari, who created his doctrine of yugen in poetry:

In the twilight of the evening, an autumn whirlwind over the fields pierces the soul... A quail's complaint! Village of Deep Grass.

The entire landscape of the poem creates a feeling of frightening and hopeless mystery. But yugen has many shades. The result of the perception of yugen should be the highest harmonious balance with the world.

The poet Fujiwara Shunzei (1114-1204) called yugen a reincarnation of mono no aware, a new expression of unchanging beauty (bi). Yugen is a new facet of that polyhedron that rotates with time; at the level of forms, only one side of it is revealed each time. In a state of peace, absolute being, all its sides are revealed. Hence the desire to experience the “beauty of Nothingness.”

Yugen is a feeling of the fragility of existing things, but poets loved the state of “wandering in uncertainty” (tadayou).

If avare is the bright yang, then yugen is the impenetrable yin... Noh Theater

Having pushed aside the courtiers, the military aristocracy contributed to the development of new forms of theatrical art. One of the postulates says: “He who entertains brings peace to the earth, he who rules brings order.” The religious-mystical, feudal-monarchical romanticism of the Noh theater fully corresponded to her tastes and requirements. The art of Noh is based on the aesthetics of Yugen. But at the end of the Kamakura era, yugen increasingly loses the spirit of sadness and acquires the meaning of brilliance. It was in the image of lush beauty that the concept of yugen came to Noh theater.

Zeami said that without yugen there is no No. He made one feel the beauty of yugen through the language of the image: “a swan with a flower in its beak”, “the beauty of a withered flower”, conducive to thoughtfulness. “It’s like spending all day in the mountains; as if he had entered a spacious forest and forgot about the way home; as if you were admiring the sea paths in the distance, at the boats hiding behind the islands... As if you were following the flight of wild geese disappearing in the distance among the heavenly clouds...”

Noh performances take place on square stages constructed from unpainted hinoki wood. Above the stage, supported by four pillars, rises a roof, similar in design to the roofs of Shinto shrines. The four pillars supporting the roof above the stage have their own names and functions in the performance. Near the rear left pillar (site-basira) they stop when they enter the stage, and the main characters of Noh plays begin the action from it. The front left pillar (metsuke-basira) serves as a guide for masked actors who cannot clearly see the stage boundary. The right front pillar is called waki-basira because the secondary actor (waki) goes to it when his functions end. Near the right rear pillar (fuebashira) there is a musician with a flute.

The stage is open on three sides, the fourth side is a backdrop wall, on a golden background depicting a green spreading stylized pine tree (a symbol of longevity and a benevolent greeting to the audience). The orchestra in the Noh theater consists of four musicians (hayashikata), who are arranged in a single row along the backdrop. Along with the orchestra, at the back wall on the left, sits a koken - a person who helps the actors on stage. He is conventionally considered invisible and can, during the action, adjust the actor’s costume, wig or mask, or give him any props.

Another interesting detail in the design of the No stage is hidden from view. Under the stage, original resonators are constructed: in several dug holes, special pots (about a meter high and about the same diameter) are suspended on copper wire so that they do not touch the ground. They give a special ringing sound to stomping, which is one of the most common elements in Noh dance technique.

The plays of the Noh theater, yokyoku (“musical piece for singing” Wink rhythmically organized what was already known. “Yokyoku texts are a motley fabric woven from phrases, passages, quotes borrowed from everywhere, taken very often in an almost unchanged form, from various, works well known to the reading public of those times. And yet, yokyoku is a completely original work,” notes N.I. Conrad, “They shine with their originality, perhaps to a greater extent than much else in Japan." yokyoku organically combined ancient poetry and prose, music and dance, personifying the principle of “unity of different things.” It is no coincidence that the yokyoku method was called “tsugihagi” - “stringing one thing on top of another”, and the style - “tsuzure no spouts” - “brocade from scraps”. But the traditional method of achieving a single thing through the balance of different things was implemented: music, gestures, plasticity, seasons - that state of harmony (wa), which, from the Japanese point of view, is initially inherent in the world, which is difficult to understand without taking into account the universality of yin-yang.

In the treatise “On the Continuity of the Flower” (“Kadensho” Wink Zeami says that even in ancient times they knew that the secret of mastery in any matter depends on the correct yin-yang ratio. During the daytime performance, the audience is in a yang (lively) mood, play it is necessary in the yin style (subdued). The success of the performance depends on the ability to balance the mood. In the evening, darkness evokes sadness - yin, which means you need to play lively so that the spirit of yang penetrates the heart, then the dark mood will be balanced with a light one. When on stage and in the audience the same thing same mood, yin or yang, there will be no success. In art But the text and manner of performance, movement and music, the style of playing and the nature of the terrain, the rhythm and season must be in tune. If the role requires energetic gestures, they must be balanced by inner softness. A skilled actor, following the rules of singing, dancing, gestures, in an effort to convey the invisible, each time gives these gestures a new coloring (kyoku), which depends on skill and intuition.The ten styles of yokyoku, each of which has its own soul, must also be in harmony. According to the principle of “unity of different things”, five types of plays are united: “kami no mono” - “about deities”, “shura no mono” - “about the spirit of a warrior”, “katsura-mono” - plays about unhappy love, “zatsu- no mono” - “plays about different things”, “kiri no mono” - “the final play”. Each one tunes the viewer in its own way, so that by the end of the performance he experiences all emotional states. Natural harmony underlies the rhythmic organization of No or the law of jo-ha-kyu alternation. Jo is a slow entry, ha is a sharp turn, kyu is a rapid movement. The actor’s play, individual scenes and the performance as a whole are subject to this principle: the first play is performed in the jo rhythm, the three subsequent ones in ri - in the kyu rhythm. Zeami says that everything has the levels of jo-ha-kyu, and No follows this. Obeying the world rhythm, which is not subject to the law of extinction, But preserves itself. In the treatise “The Mirror of a Flower,” Zeami notes that life has a limit, but No has none. Zeami’s frequent appeal to the image of a “flower” attracts attention. One might say that this is one of the central concepts of his theory. With the word “flower” he denoted the allegorical beauty inherent in all art. Flowers do not bloom all the time, they bloom at certain times of the year, and it seems surprising, extraordinary, it delights. The art of Noh also seems unusual. If an actor knows many roles, he can choose the one that suits the time and the mood of the viewer. This shows the resemblance to a flower that blooms at a certain time. Each actor should have his own flower corresponding to his skill. The flower of acting, like the flower of poetry, grows from the heart (kokoro). Success will accompany the performance when “a flower, amazing and unusual, has one heart.”

The flower personifies the unity of the unchanging and the changeable in art: on the one hand, it continues the life of the seed, on the other, it blooms in a new way every time. Zeami said that when flowers fall, they bloom again. And this is their extraordinary nature. Zeami refers to the nature of changeable (ryukosei). What’s remarkable is that, when flowers fall, they turn into other things. Yugen is the flower that represents this change.

After the transition of consciousness from visible beauty, the “charm of things” to the beauty of the invisible - “yugen”, makoto began to be understood as the truth of non-existence, which is associated with conventional forms, with the symbolism of No.

One and the same object on stage could mean a variety of phenomena and movements of the soul. The fan in the actor’s hands represents: a brush, a sword, a wine cup, rain, autumn leaves, a hurricane, a river, the rising sun, anger, rage, peace. The subject is multifaceted and depends on alternating moments, in each of which the Tao is manifested; in itself it is not significant, but with its help the truth is extracted from oblivion. It is not surprising that given the feeling of the universal interconnectedness of things, Noh theater, like other forms of art, is intended to maintain order in the world and perform a world-building function. The purpose of No is to soften the hearts of people, to act on the feelings of higher and lower; become the basis of longevity and happiness; become the path to a wonderful and long life. Sabi in Basho's haiku

No previous mood is required to embody the beauty of sabi. In order to see its non-random essence in the most inconspicuous object, you only need to be able to forget yourself.

Here a leaf has fallen, Here another leaf is flying in an icy whirlwind.

It is no coincidence that Basho’s style is called “authentic” (shofu).

This is what Hattori Doho, a student of Basho, said about the famous poem

Old pond! The frog jumped. splash of water

“A frog that lives in water jumped into an old pond. There was a splash of water. A haikai sounded in the croaking of a frog that jumped from a grassy bank. Everything you see and hear, everything you feel is haikai. This is the truth of art."

When Basho was studying Zen with Master Butcho, he one day asked him: “What have you been doing these days?” Basho replied: “The rain has stopped, the moss is so green.” Butte: “Which came first, the Buddha or the green moss?” Basho: “Did you hear? The frog jumped into the water."

The student, not hearing the teacher, answers inappropriately, but freeing his mind, does what the teacher wants from him.

We can consider that from this moment a new era in haiku began. Before Basho, haiku were treated as a game, they were not connected with life. Basho, whom the master asked about the true nature of things that existed before the world of phenomena, saw a frog jumping into an old pond, and this sound gave birth to silence... The poet suddenly discovered the source of life, and he began to follow every movement of his thought, as she came into contact with the constantly changing world of phenomena. Basho was a poet of eternal loneliness.

Haiku is not determined by form. Although there are a number of rules, for example, alternating words of 5-7-5 syllables, the presence of a seasonal word. It is determined by the phenomenon itself and the internal mood of the one who contemplates this phenomenon. It reflects him directly and accurately; nothing stands between the poet and nature, which has found its expression. Basho said that you need to learn pine from pine, bamboo from bamboo, to comprehend the subject by delving into it. That is, bring your mind into line with emptiness, thus turning into the object itself. And only under this condition will a poem be born.

The poet focuses on the internal, delves into the individual until the unity is revealed, penetrating into the individual, he comprehends the nature of the universal. At the moment of insight, the dependence of things on each other ceases at the level of true, from the point of view of Buddhism, reality. Since everything is in motion, you need to trust it so as not to come into conflict with it. Basho said that the haikai should not stop for a moment. When looking at creativity as a breakthrough into Nothing, art was understood as a continuation of life, and the artist as one who makes one feel the connection of everything with everything. At the same time, sabi is life itself. Basho said that sabi is the coloring of a poem; it is not at all necessary to give a scene of loneliness. If a person, preparing for war, puts on heavy armor or, going to a party, dresses up in bright clothes, and this person is not young, then there is sabi in this. Basho’s techniques are simple, the strength of his poetry is in balance, in the “unity of different things”: color, smell, sound. It is thanks to this that haiku is likened to life itself.

Sabi allowed us to penetrate deeper into makoto - the truth of things. Basho discovered the essence of nature in sabi. He has advanced further than others in understanding Makoto. Basho found sabi in the unity of the unchangeable (fueki) and the changeable (rikyu). Basho understood sabi as the highest law of nature, human life and art.

Sabi is an echo of the eternal, unchangeable in the transitory, changeable, a feeling of the fragility and fleetingness of life, at the same time its infinity.

Hence the touch of sadness in the verses marked with sabi, but it is a quiet, peaceful sadness. Tea ceremony

In the art of the 15th-16th centuries, the style of wabi - peace, silence, modesty - was something that was opposite to yugen. Wabi is a deserted shore on which stands a lonely fisherman's hut, small buds breaking through the thickness of the snow in a mountain village. Wabi is the beauty of simplicity, the beauty that comes from the life force hidden behind the rough surface. It is colorless, but behind the veil of colorlessness there is a secret invisible force. Wabi is the ability to be yourself, to follow the natural path.

During the period of the return of the inclination to simplicity and rigor, the tradition of the tea ceremony developed, which had its own philosophy, its own aesthetic requirements, and traditions. The relationship between man, nature and art found full expression in it.

The tea ceremony master Sokei (16th century) said that the original purpose of wabi is to make one feel the purity and uncontamination of the Buddha’s abode. That is why the owner and guests, as soon as they enter the modest tea room, cleanse themselves of earthly dust and conduct a conversation with their hearts. Therefore, there is no need to worry about rules and manners. Just light a fire, boil water and drink tea. This will be the tea ceremony.

As the legend goes, one day, while sitting in meditation, Bodhidharma felt that his eyes were closing and he was falling asleep. Then, angry with himself, he tore out his eyelids and threw them to the ground. An unusual bush with succulent leaves grew at this place. Later, Bodhidharma's disciples began to brew these leaves with hot water to maintain vigor. This is how tea appeared...

As a secular event, the tea ceremony appeared in the 15th century, then at the end of the 15th century it was reorganized by the famous “chajin” (tea master) monk Sen no Rikyu. There was the concept of “chado” (the way of tea) - the path of purity and refinement, achieving harmonious unity with the outside world through the ritual of the tea ceremony.

The tea ceremony took place in a small tea house located in the depths of the garden, which was an artistic phenomenon and was created according to special laws. A path of irregularly shaped stones placed among mosses led to a source of water, where hand washing was performed, then, after choosing the main guest, they entered through a very low door into the tea house. There should be no more than five guests; like-minded people were invited. Poetry, philosophical and aesthetic problems were discussed. The very situation inside the tea house, where twilight reigned, was conducive to such a conversation. Three topics - money, illness, politics - were taboo. Yasunari Kawabata said well about the tea ceremony: “If “wabi-sabi”, so highly valued in the Way of Tea, which prescribes “harmony, respect, purity and tranquility,” personifies the wealth of the soul, then a tiny, extremely simple tea room embodies vastness space, the infinity of beauty... A meeting over tea is the same meeting of feelings.”

Utensils used in preparing tea, the room in which the ceremony takes place, a specially selected and placed in a vase composition of two or three branches, a silk scroll hanging above it on the wall with a painting or a calligraphic inscription corresponding to the occasion, the surrounding landscape, and finally, clothing , the behavior of the participants and the content of their leisurely conversations - everything should be in perfect harmony, the harmony of artlessness, restraint, simplicity, helping a person get closer to the surrounding nature, dissolving in it. Nothing should interfere with creating a mood of quiet contemplation or interfere with reflection.

The presence of “pure”, and therefore, from the Japanese point of view, useless beauty is excluded. The essence of the tea ceremony is that it expresses the aesthetics of real life, where utility is the first principle of beauty. In total, for the tea ceremony there should be twenty-four necessary items - “chaki”, among them a tea bowl “chawan”, “mizusashi” - a vessel for cold water, boxes for tea “kogo”, a bronze cauldron, a wooden ladle made of bamboo and others. All items for the tea ceremony, except for their immediate purpose, were objects of contemplation.

Works of Japanese applied art have long emphasized the direct practical value of the thing itself. That is why connoisseurs of the tea ceremony, known for their exquisite taste, abandon Chinese porcelain and turn to folk art. The thick walls of the bowl retain heat well. The rough, unglazed bottom of the bowl is placed on the palm, recalling the nature of the material - the clay from which it is made. Each bowl is unique, not repeated either in shape or decoration. The ceramics are made specifically without the help of a potter's wheel - hand sculpting helps to better understand the thoughts and aspirations of the author, embodied in the creation of this work of art.

In ceramics for the tea ceremony, one of the main qualities of Japanese applied art was most reflected - wabi-sabi (the beauty of the simple, ordinary).

Japanese masters preferred clear, calm forms, without pretentiousness or artificiality. The decor on vases, bowls, bottles also corresponds to the nature of the form... Peculiarities of national suicide

I would like to touch upon the aesthetic side of the samurai’s attitude to death, which has been repeatedly sung in literature and repeatedly confirmed by historical examples. Life was seen as a link in a chain of rebirths. The intrinsic value of earthly life for a Buddhist was small. The Buddhist thesis about the impermanence of all things underlies the entire Japanese culture.

What can your body be compared to, man? Life is illusory, like dew on the grass, like the flickering of lightning.

This poem by the Zen master Rohan reflects a universal truth that does not require any confirmation. This idea of death was inherent in samurai. They saw their destiny in being “like falling cherry blossom petals” and dying in battle, “like jasper breaking on a cliff.” Over time, death in the name of duty began to be perceived in the samurai environment as a rather difficult, but not devoid of aesthetic pleasure, stage of self-improvement. They talked a lot and deeply about death, they admired death, they strived for a beautiful death. One of the samurai, who fell at the hands of an assassin, left the following lines:

Neither heaven nor hell can trouble me anymore, and in the moonlight I stand unshakable - not a cloud on my soul...

In the samurai environment, the ability to abstract from the bustle of the world, from the prose of life, and from the atrocities of wartime was highly valued. From an early age, the ability to see “eternity in a flower’s cup” was nurtured in boys and girls. A way of life in which a person can enjoy the beauty of the landscape even on the verge between life and death was called furyu, which means “wind and stream.” Such a worldview made it possible to invariably perceive life as “wind and flow” in all its ephemeral fullness. The most perfect embodiment of this philosophy was the widespread custom among samurai of composing a “farewell” poem before death (most often in the genre of landscape lyrics).

Let us cite as an example a specific incident that occurred relatively recently, emphasizing the importance of the poetic tradition.

On March 17, 1945, Lieutenant General Kuribayashi Tadamichi, commander of the Japanese forces at Iwo Jima, radioed three tanks to General Headquarters before rushing to attack the enemy with his remaining eight hundred soldiers. One of them:

The enemy is not defeated, I will not die in battle, I will be born seven more times to pick up the halberd!

The words express the hope of being reborn seven times in order to take revenge.

Let us remember the Japanese customs directly related to death: decapitation, ripping open the abdomen, shinju.

The Japanese custom of cutting off the head of an enemy warrior comes from the Age of Wars in Ancient China, where a warrior received a promotion by one rank if he obtained the head of a noble enemy in battle. The expression shukyu o ageru - “took the head and got promoted” - comes from there.

The origins of the belly-cutting ritual remain unclear. The earliest surviving document describing belly-ripping attributes it to a female deity: the goddess Omi, pursuing her husband, reached a place later called Harasaki ("Belly-Ripping" Wink), but, inflamed with anger and malice, cut her own belly with a sword and threw herself into the swamp.

By the 11th century. the custom had already entered into practice and was supposed to serve as a way of showing courage, or avoiding dishonor at the hands of enemies. In the XIV century. the ritual spread widely. Suicide began to be viewed as a manifestation of the highest heroism, a demonstration of strength and self-control. This attitude towards life and death is clearly shown in the classic Japanese epic. The Tale of the Great Peace describes 2,640 cases of such suicides. The stomach was also ripped open to follow the master after his death. In a number of cases, death for one’s master took the form of mass suicide: “The prince asked: “How should one kill oneself?” Yoshiaki, holding back the gushing tears, said: “That’s it...”. And, without finishing speaking, he pulled out the sword, turned it towards himself, plunged it into his left side and cut several ribs towards his right side. Then he took out his sword, laid it in front of the prince, fell on his face and died. The prince immediately took the sword and looked at it. Since there was blood on the hilt, the prince wrapped it with the sleeve of his robe, exposed his snow-like body and, plunging the sword near his heart, fell on the same headboard as Yoshiaki.

All those who were with the prince exclaimed: “We, too, follow the prince!” They said a prayer to the Buddhas with one voice, and everyone immediately committed hara-kiri. Seeing this, the warriors, numbering more than three hundred, who were standing in the courtyard, began to pierce each other with swords and fell to the ground with their chests” (“Taiheiki” 117, p. 212)

In the 17th century Under Tokugawa, samurai who committed a shameful act began to be sentenced to have their bellies ripped open. The harakiri procedure (the Japanese themselves tend to use the word “seppuku” or “kappuku” Wink, which was used as punishment, was arranged especially magnificently. The act of harakiri was usually performed in the master’s house at night or in the evening. The yard was sprinkled with coarse sand, and the place of the act itself was covered with thin mats, which were covered with white linen; a red woolen blanket was laid on top.

Ripping open the abdomen does not lead to immediate death; death can be painful, messy and long. At one time there was a rule that prescribed opening the abdomen first horizontally, then vertically, followed by a fatal blow - in the back or neck. According to legend, General Nogi Maresuke (1849-1912), who committed suicide on the day of the funeral of Emperor Meiji (1852-1912), performed exactly this procedure.

Going through all three stages requires incredible fortitude. This explains the frequent presence of an assistant, kaishaku or kaishakunin, who had to cut off the head at one of two moments.

In the first case, the kaishaku cut off his head at the moment when the condemned samurai, already preparing for death, bent over a short sword or dagger lying in front of him on a ceremonial tray. Here there was no opening of the abdomen at all. During the Tokugawa period, this method became widespread in its most stylized form, and instead of a sword, a fan was often placed on the tray.

In another case, the kaishaku waited until the person he was supposed to help die passed the first or second stage himself. This was the path chosen by a samurai named Taki Zenzaburo on March 2, 1868. His suicide is described in detail by Sir Ernest Mason Satow (1843-1929), secretary of the British Legation in Edo.

Typically, suicide in Japan is committed alone, but unlike other countries, group suicides often occur here.

So, in the mid-50s, more than 1,200 such cases were recorded annually. Quite a lot of group suicides are still happening. Among them, lovers invariably take first place. Such suicides are called shinju (suicide by conspiracy) or joshi (romantic suicide) in Japan; Such suicides first began to be practiced on the eve of the Edo period. They are close in spirit to various types of solemn blood oaths: tearing out nails, piercing an arm or leg with a dagger, cutting off a finger, etc. Suicides of lovers were committed by opening veins, cutting throats, hanging... Around the middle of the 17th century. these types of suicides were banned, but they have not disappeared to this day... * * *

with comments, questions and additions, you are welcome to my LJ