Edo (1600–1868)

In 1603, Tokugawa Ieyasu, the third unifier of Japan, received from the emperor the title of military ruler of the country - shogun.

The capital became the city of Edo (later renamed Tokyo), where Ieyasu set up his headquarters.

Edo was originally a small fishing village, but quickly grew into a huge city.

For more than two centuries, from 1641 to 1853, the Tokugawa government pursued a policy of self-isolation of Japan from the outside world. The reason for its introduction was the uprising of Christians on the Shimabara Peninsula. The uprising was suppressed, and Christianity was strictly banned. Moreover, the Japanese were not allowed to leave the country, and those living abroad were not allowed to return. Of the foreigners, only the Chinese and the Dutch could stay in Japan, but their activities were limited to the port of Nagasaki.

On the other hand, life in the country became orderly and calm, and the state was protected from external influence. The rule of the Tokugawa clan ensured 250 years of peace in the country. A unified Japan became a prosperous state. Cities grew, and with them the population of the country increased. Despite the existing strict rules of behavior regulated by the principles of Confucian morality, the level of education in the country was very high.

The Edo era also saw a flourishing of urban culture.

Many written monuments dating back to this period have been preserved, thanks to which it became possible to learn in more detail about the customs, mores and language of that time. During the Edo period, the main state ideology was neo-Confucianism

, or

Zhuxianism

(the teaching of one of Confucius’s followers, Zhu Xi), and on the basis of Confucian ideas, many syncretic teachings arose.

the Suika Shinto

school was created by merging Confucianism with Shinto .

Various literary genres and trends have developed rapidly. In prose, drama, and poetry, brilliant authors appeared, whose works are still highly valued in Japan and throughout the world. Among them are the novelist Ihara Saikaku (1642-1693), the playwright Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653-1724), and the poet Matsuo Basho (1644-1694). Thanks to Basho and his followers, the three-line haiku genre became the leading genre in Japanese poetry. On its basis, satirical and humorous senryu poems also arose, which still have many fans among the Japanese.

During this period, many objects and customs appeared in the life of the Japanese, which are still actively used in everyday life. These include straw tatami mats, wooden shoji partitions, and even sitting on the floor in the Japanese style - seiza.

The smooth rule of the bureaucratic apparatus of the Tokugawa shoguns failed at the beginning of the 19th century. The economic situation in the country worsened, peasant riots and protests against the shogun's policies began to occur.

In 1853, an American squadron led by Commander Perry arrived in Japan, and under American pressure, the Japanese government was forced to end its policy of self-isolation. The last years of the Tokugawa shogunate, which passed under the slogans of anti-shogun protests, are called Bakumatsu (“End of the Shogunate”, 1853-1867).

Orthodoxy in Tokyo

In 1871, at the direction of Equal-to-the-Apostles Nicholas of Japan, his first Japanese convert, Pavel Sawabe, visited Tokyo and assessed the situation in the capital as very favorable for the beginning of the preaching of Orthodoxy. The following year, Saint Nicholas himself moved to Tokyo and began to establish a new headquarters for the Japanese Mission on Surugadai Hill. Soon the first Orthodox church in the capital, the Nativity of the Cross Church, and the first Orthodox school, transformed into a theological seminary in 1875, were opened here. Equal to the Apostles Nicholas paid great attention to preaching in the new capital - houses for preaching were set up in different parts of the city, around which the first communities of believers quickly began to grow. In 1884-1891, with funds donated from Russia, the Tokyo Resurrection Cathedral (in Japanese usage - “Nikorai-do”) was erected on the mission site, which became a symbol of Orthodoxy not only in the capital, but also in Japan. From 1906, the nascent Japanese Orthodox Church was organized as the Tokyo Diocese with a see at the Cathedral of the Resurrection. Moreover, during the years of the sainthood of Nicholas of Japan, the leading Tokyo parishes could compare with the cathedral in both numbers and liveliness. At the peak of missionary activity in Tokyo, there were more than a dozen Orthodox communities - for example, in 1911 there were a cathedral parish, an Ascension parish in Kanda, an Epiphany parish in Koojimachi, a Trinity parish in Shitaya, a Transfiguration parish in Asakusa, a Peter and Paul parish in Honjo, a parish in Hongoo, parish in Kyobashi-Nihonbashi, parish in Shinagawa, parish in Fukagawa, parish in Hori-no-Uchi-Ooji, parish in Senju-Mikawajima [8].

The turmoil experienced by the Japanese Church in the century - the cessation of aid from Russia after the October Revolution, the Great Kanto earthquake that destroyed half the city and severely damaged the cathedral in 1923, the bombing of World War II, the politicized unrest during the Cold War - led to the collapse of missionary activity and the gradual disappearance of the majority of Tokyo parishes After World War II, only two Orthodox churches survived in the capital - the Resurrection Cathedral and St. Nicholas Church on the cathedral site, so the lives of all Orthodox Christians in the city were concentrated here. The only historical parish that was able to restore its own temple was the Koodimachi-Yotsuya parish, which since 1954 has settled at the new temple in Yamate. The remaining old Japanese Orthodox communities of the capital, one after another, were merged into a single parish of the Resurrection Cathedral - a process that was completed under Metropolitan Feodosius of Tokyo. At the same time, the parishioners of the Japanese Patriarchal Deanery formed after the war (since 1970 - the Patriarchal Metochion), which largely consisted of Russians, maintained a separate liturgical life in the St. Nicholas House Church.

The revival and strengthening of the Russian Orthodox Church since the end of the century, as well as the wave of emigration from the countries of the former USSR after its collapse, were reflected in church life and in Tokyo. In particular, in 2005, the foundation was laid for the St. Nicholas Monastery on the cathedral site, and in 2008, the Japanese metochion of the Russian Church rebuilt a new Alexander Nevsky Church in Meguro.

The Saints

- Equal. Nikolai (Kasatkin) (+ 1912) - educator of Japan, archbishop. Tokyo

Monasteries

- Nicholas of Japan (male)

Temples

- Alexander Nevsky in Meguro at the metochion of the Russian Orthodox Church

- Epiphany in Yotsuya (destroyed in 1945, replaced by the Nativity Temple in Yamate)

- Resurrection of Christ, Cathedral

- Nicholas of Myra, brownie, at the metochion of the Russian Orthodox Church

- Nicholas of Myra, “small temple” (dismantled in 1962)

- Nicholas of Japan, chapel (adapted for the temple of the St. Nicholas Monastery)

- "Nikorai-do" (see Tokyo Resurrection Cathedral)

- Nativity of Christ, cross (dismantled in the early 1880s, replaced by the Resurrection Cathedral)

- Nativity of Christ in Yamate

- Epiphany of the Lord in Koojimachi (dismantled c. 1911, replaced by the Nativity Church in Yamate)

- Church at the Russian Embassy (abolished in the 1920s)

Educational establishments

- Tokyo Theological Seminary

- Tokyo Catechetical School (inactive)

- Tokyo Girls' School (inactive)

Art of Japan during the Edo period, 1615-1868

Author: Hyosan March 31, 2014 at 01:40 pm in the category History of Art

By the end of the 1630s, contact with the outside world was cut off by an official decree banning everything foreign. During the period of more than two centuries of self-isolation, there was a revival of traditional values, traditional art, which not only strengthened, but also transformed into the most refined.

In a tightly controlled feudal society ruled for over 250 years by the descendants of Tokugawa Ieyasu (1542-1616), Japanese artistic creativity developed not among the leaders of the conservative military class, but among the two lower classes according to the Confucian social hierarchy, that is, among the artisans and merchants. Although these two social classes - artisans and merchants - were officially considered the rabble, they still had enough freedom to develop their own aesthetic tastes.

Inro, decorated with a stylized figurine of a Portuguese musician. Wood with black and gold varnish.

Trade relations with Chinese, Dutch and Portuguese merchants were allowed only in Nagasaki. The mutual fascination with which the Japanese and Europeans viewed each other after first meeting back in the late 16th century was represented particularly in Japanese fine art. The illustration shows a Japanese inro - a container for storing medicinal herbs and other small items, which was worn around the waist. The surface of the inro is decorated with images of three Portuguese men dressed in characteristic ruffled collars, as well as trousers and jackets of European style.

Koto musical instrument with case and pouch. Early 17th century. Several types of wood, ivory, tortoiseshell inlay, gold and silver inlay.

Trade with China stimulated the development of Japanese porcelain. And since subjects from the literary works of the Ming Dynasty became the most popular in porcelain painting, this culture began to seep into the artistic circles of Kyoto and Edo.

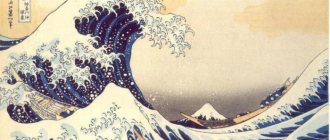

By the end of the 17th century, three branches of creative expression flourished in Japan. The revival of Heian culture, intended for aristocrats and the cultural society of large cities, created a large number of schools of painting and a new style, which later became known as Rinpa. In Edo, rebuilt after a great fire in 1657, literature and the arts began to gain great interest, leading to the emergence of Kabuki theater and with it the tradition of Ukyo-e prints.

In the 18th century, a Japanese response to Chinese literary art appeared, created by Chinese monks from the Manpuku-ji Temple near Kyoto. The monks created an entirely new style of painting known as Bijin-ga (lit. "literary painting"), or Nanga ("southern school painting").

Throughout the 18th and early 19th centuries, these three very different styles became the primary styles for most Japanese artists and craftsmen.

Ogata Korin (1658–1716), Stormy Waves, c. 1704. Two screen panels; colored and gold ink on gilded paper; 146.6 x 165.4 cm.

Many artists and poets from East and West have sought to capture the image of frailty and transience through sea waves. Ogata Korin's Stormy Waves is one of the most striking representations of this amorphous, elusive form. The image of the elements takes on a terrifying appearance thanks to the long waves, like the tentacles of an octopus. The technique is ancient Chinese, with two hands held in one hand.

A page with a poem mounted like a scroll; early 17th century. Painting by Tawaraya Sotatsu, calligraphy by Honami Koetsu (1558-1637). Ink on paper with gold and silver decoration; 20 x 17.8 cm.

The classic poem, inscribed in calligraphy by Honami Koetsu on a square piece of paper, is embellished with Tawaraya Sotatsu's painting of cherry blossoms against a background of golden clouds.

Okumura Masunobu (1686–1764), Yukihira and the maidens. OK. 1716–35. Scroll; colored ink on silk; 84.1 x 32.7 cm.

A young man, walking with a charming courtesan, plucks a hair from his beard. In this painting, Okumura Masunobu, one of the versatile artists and lover of theater and brothel scenes in woodcuts, presents an urban parody of the story of the poet and statesman Ariwara Yukihira (818–893). Several stories tell of Yukihara's love for the sisters Matsukatsu and Murasama.

Tag: Fine arts