Class system

Japanese society in the 17th-18th centuries was divided into classes based on professional characteristics. Traditional historiography distinguishes four main classes:

- Military;

- Peasants;

- Craftsmen;

- Traders.

The latest historical science identifies slightly different ones:

- Samurai;

- Peasants;

- Bourgeois (craftsmen and traders);

- Aristocrats;

- Clergymen.

The society was controlled by military samurai, who were responsible for the defense of the country and the performance of administrative and civil functions. The military had the privilege of wearing two samurai swords and the right to have a surname. The maintenance of military power, in turn, fell on the shoulders of the townspeople and peasants, the main producers of products and the main stimulators of trade turnover, and those who pay taxes.

Definition 1

Samurai are feudal lords in Japan, ranging from daimyo (major princes) to ordinary warriors; in a narrow sense - the military class of small nobles.

Finished works on a similar topic

- Course work: Socio-economic development of Japan in the 18th-19th centuries 440 rubles.

- Abstract Socio-economic development of Japan in the 18th-19th centuries 250 rubles.

- Test work: Socio-economic development of Japan in the 18th-19th centuries 250 rubles.

Receive completed work or specialist advice on your educational project Find out the cost

The class system made it possible to maintain stability within Japanese society, in which different professional groups complemented each other. The estates did not have a hereditary nature and did not have strict boundaries, which allowed townspeople and peasants to become samurai for their services, and the samurai themselves to accept children from merchant or rural families into their families.

Outside the class system there was a group of pariahs, “untouchables.” Their professional occupations were waste disposal, cleaning, and leather tanning. They were the object of contempt from representatives of all other classes.

Japan in the 19th century

Page 1 of 2

Japan is a state in East Asia, occupying four large and approx. 4 thousand small islands.

The formation of statehood on the Japanese Islands dates back to the early Middle Ages (4th-7th centuries). At the same time, Buddhism penetrated into the Land of the Rising Sun from China, becoming the basis of the state ideology along with a set of traditional religious beliefs called Shinto (Japanese - the way of the gods). From the beginning In the 17th century, the feudal Tokugawa clan established dominance over all other principalities of Japan.

For almost 270 years, real power in the country did not belong to the so-called emperors. Chrysanthemum dynasty, and military dictators (shoguns) from the Tokugawa clan, who owned a quarter of the country's territory. The remaining lands were in the hands of the shogun's vassals - appanage princes. Their number in the 1st half. 19th century was 270.

The government of the shogun was located in the city of Edo, while the emperor and his court constantly resided in the ancient capital of Kyoto. To prevent conspiracies against the political system, a hostage system was in effect since 1635, according to which princes were obliged to alternate a year of residence in their domains with a year of stay in Edo. Moreover, in the absence of their husbands, their wives and children remained in the capital as honorary hostages.

During the shogunate, a rigid class hierarchy was established. Traditional Japanese society was divided into four classes - nobles (samurai), peasants, artisans and merchants.

The economy of the southwestern principalities of Satsuma, Choshu, and Tosa developed at the fastest pace. The acreage gradually expanded, and peasant payments in kind for the use of land (rent) were replaced in some principalities with money. Home industry and manufactories in spinning, weaving, paper production, food production, and pottery developed rapidly.

The cessation of internecine wars and the self-isolation of the country since 1637 caused the samurai to lose their role as professional knight warriors. Financial difficulties forced them to seek side jobs as teachers, artisans, small traders and entrepreneurs. Usury became widespread. In the village, a layer of wealthy peasants emerged, who, however, due to their social status remained powerless.

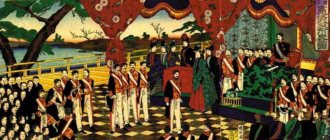

Attempts by the Western powers and Russia to establish formal diplomatic relations with the shogun's government ended in failure until the middle. 19th century. Only a military demonstration by the American squadron in 1854 forced the Japanese authorities to sign the Treaty of Peace and Friendship. A document similar in content was agreed upon between Russia and Japan in 1855 (Shimoda Treaty). The border demarcation of both empires in the Kuril Islands area was important.

Following the USA and Russia, Japan was “discovered” by other Western countries, primarily Great Britain, France, the Netherlands, etc. The involvement of the Land of the Rising Sun in world trade significantly accelerated the crisis of traditional relations in the social, political and economic spheres. The capitulation of the government of the last shogun Keiki to the powers caused massive discontent among both a significant part of the samurai and other social strata. After all, cheap imported goods entering the domestic market through “open” ports undermined local manufacturing and handicraft production (by the mid-1860s there were 420 manufactories in the country).

A wave of peasant riots and uprisings of the urban lower classes swept across the country. A particularly stubborn struggle unfolded in the southwestern principalities (Satsuma - 1858, Budzen, Aizu, Iwami - 1865-1867). Unlike European countries, samurai, rich merchants and wealthy peasants played a leading role. With their slogan, which united the heterogeneous elements of these protest movements, the rebels chose a call for the restoration of imperial power, usurped by the Tokugawa shoguns. Having concluded a military alliance in the beginning. 1866 and using the support of France, the rulers of the southwestern principalities managed to repel the punitive campaign of the shogun's troops in July of the same year. On January 3, 1868, the leaders of the opposition movement seized the palace of the 15-year-old Emperor Mutsuhito in Kyoto and on his behalf issued a decree to overthrow the shogun Keiki. All power passed into the hands of Mutsuhito and his supporters. In a solemn oath to the emperor, the leaders of the movement promised to carry out a set of socio-political and economic reforms with the aim of accelerating the modernization of the country. Thus began the Meiji democratic revolution, which at the first stage took the form of a civil war. Having broken the resistance of Keiki's troops throughout the country by June 1869, the emperor's followers began to carry out radical reforms in all spheres of life. The period of Mutsuhito's reign was called Meiji. The elimination of the feudal class system, the proclamation of the free purchase and sale of real estate, the transition to a single land tax, as well as the proclamation of the possibility of choosing a profession and place of residence contributed to the formation of a national market. The abolition of principalities and the introduction of prefectures led to the consolidation of the empire, the capital of which was Tokyo (formerly Edo). The reform of public education was of great importance for the modernization of the country, after which modern educational institutions, including universities, began to be created. K ser. 1870s real power in the country was concentrated in the hands of the most active former samurai, who turned into officials. Under the emperor, a council of influential dignitaries - genro - arose. Steps were taken towards the adoption of a new constitution and parliamentary elections. The experience of the German Empire was used as a model. The Meiji government's main goal was to eliminate Japan's economic and military backwardness as soon as possible. The course for its modernization was carried out under the slogan “Rich country and strong army!” A serious step in this direction was the introduction of universal conscription in 1872.

- To the begining

- Back

- 1

- Forward

- In the end

Sela

The Japanese economy of the Edo era was semi-subsistence in nature and dependent on tribute rice supplies. Its collection was carried out in villages by local officials - village heads nanusi or shoya, heads of fives and peasant delegates who controlled communal arable land, mountains and waters, and also performed various administrative functions. Decisions were made collectively. Residents of the villages were divided into fives, their members were in mutual responsibility, jointly paying tribute and preventing the commission of crimes. In one village, there were customs of mutual assistance between the fives.

Do you need proofreading or review of academic work? Ask a question to the teacher and get an answer in 15 minutes! Ask a Question

In order to stabilize the supply of tribute in rice, the shogunate banned the sale of land and limited the peasants, concentrating them exclusively on field work and various duties. Most villages paid taxes on time, considering them a matter of national importance. However, sometimes exorbitant exactions forced peasants to complain to the daimyo or directly to the shogun, or, in extreme cases, to start peasant uprisings.

Agriculture

With the beginning of peaceful life, the Japanese actively began to develop their agriculture. By order of the authorities, old flood fields were expanded and new ones were created by developing previously untouched virgin lands and carrying out large-scale irrigation work. During the first century of the shogunate, the area of arable land doubled. At the same time, labor productivity increased, which was facilitated by the appearance of new tools - hoes and a thousand-tooth thresher, as well as the use of fertilizers - rapeseed oil and dried sardines. The cultivation of commercial crops—cotton, hemp, rapeseed, tea, indigo dyes, and safflower—reached a wide scale.

Industry and transport

The rapid development of agriculture contributed to the rise of industry and population growth. As a result of the expansion of settlements near the castle, the demand for wood necessary for housing construction increased, which pushed the development of forestry and woodworking. In addition, industrial fishing arose - sardines, bonito, whales, heringa and Kombu seaweed were caught. At the same time, salt production began to develop on the coast of the Inland Sea of Japan. The demand for the work of urushi varnishers, foundries and potters increased.

Japanese miners discovered new gold mines on Sado Island, silver mines in the Ikuno area of Settsu Province, and copper mines in the Ashio area of Shimotsuke Province. These metals were used to mint coins that were in circulation throughout Japan.

The shogunate paid due attention to the development of transport infrastructure. Five roads were built in the country, of which the main one was Tokaido - the route from Edo to Kyoto. Guest yards for travelers were evenly built along the roads. An efficient postal system was established using hikyaku messengers. In addition to land routes, water routes became of great importance, along which maritime trade between regions was actively carried out.

Socio-economic development of Japan in the 18th-19th centuries

Japanese society in the 17th-18th centuries was divided into classes based on professional characteristics. Traditional historiography distinguishes four main classes:

- Military;

- Peasants;

- Craftsmen;

- Traders.

The latest historical science identifies slightly different ones:

- Samurai;

- Peasants;

- Bourgeois (craftsmen and traders);

- Aristocrats;

- Clergymen.

The society was controlled by military samurai, who were responsible for the defense of the country and the performance of administrative and civil functions. The military had the privilege of wearing two samurai swords and the right to have a surname. The power of the military, in turn, fell on the shoulders of the townspeople and peasants, the main producers of products and the main stimulators of trade turnover, and those who pay taxes.

Definition 1

Samurai are feudal lords in Japan, ranging from daimyo (major princes) to ordinary warriors; in a narrow sense - the military class of small nobles.

The class system made it possible to maintain stability within Japanese society, in which different professional groups complemented each other. The estates did not have a hereditary nature and did not have strict boundaries, which allowed townspeople and peasants to become samurai for their services, and the samurai themselves to accept children from merchant or rural families into their families.

Can not understand anything?

Try asking your teachers for help

Outside the class system there was a group of pariahs, “untouchables.” Their professional occupations were waste disposal, cleaning, and leather tanning. They were the object of contempt from representatives of all other classes.

Sela

The Japanese economy of the Edo era was semi-subsistence in nature and dependent on tribute rice supplies.

Its collection was carried out in villages by local officials - village heads nanusi or shoya, heads of fives and peasant delegates who controlled communal arable land, mountains and waters, and also performed various administrative functions. Decisions were made collectively.

Residents of the villages were divided into fives, their members were in mutual responsibility, jointly paying tribute and preventing the commission of crimes. In one village, there were customs of mutual assistance between the fives.

In order to stabilize the supply of tribute in rice, the shogunate banned the sale of land and limited the peasants, concentrating them exclusively on field work and various duties.

Most villages paid taxes on time, considering them a matter of national importance.

However, sometimes exorbitant exactions forced peasants to complain to the daimyo or directly to the shogun, or, in extreme cases, to start peasant uprisings.

Cities

As a result of the introduction of the class system and the separation of vassals from their land plots in the provinces, the samurai were relocated to the castle cities of the overlords.

In order to ensure the livelihoods of such samurai settlements, merchants and artisans moved to them, who became known as petty bourgeois. The authorities imposed monetary taxes on them for transportation and production.

The richest and most famous citizens could join the city government and perform administrative work in the city.

Agriculture

With the beginning of peaceful life, the Japanese actively began to develop their agriculture. By order of the authorities, old flood fields were expanded and new ones were created by developing previously untouched virgin lands and carrying out large-scale irrigation works.

During the first century of the shogunate, the area of arable land doubled. At the same time, labor productivity increased, which was facilitated by the appearance of new tools - hoes and a thousand-tooth thresher, as well as the use of fertilizers - rapeseed oil and dried sardines.

The cultivation of commercial crops—cotton, hemp, rapeseed, tea, indigo dyes, and safflower—reached a wide scale.

Industry and transport

The rapid development of agriculture contributed to the rise of industry and population growth. As a result of the expansion of settlements near the castle, the demand for wood necessary for housing construction increased, which pushed the development of forestry and woodworking.

In addition, industrial fishing arose - sardines, bonito, whales, heringa and Kombu seaweed were caught. At the same time, salt production began to develop on the coast of the Inland Sea of Japan. The demand for the work of urushi varnishers, foundries and potters increased.

Japanese miners discovered new gold mines on Sado Island, silver mines in the Ikuno area of Settsu Province, and copper mines in the Ashio area of Shimotsuke Province. These metals were used to mint coins that were in circulation throughout Japan.

The shogunate paid due attention to the development of transport infrastructure. Five roads were built in the country, of which the main one was Tokaido - the route from Edo to Kyoto.

Guest yards for travelers were evenly built along the roads. An efficient postal system was established using hikyaku messengers.

In addition to land routes, water routes became of great importance, along which maritime trade between regions was actively carried out.