General information

In the first half of the 16th century, civil strife among the samurai families did not stop in Japan. When state fragmentation became the norm of socio-political life, forces appeared in the country that tried to restore unity. They were led by Oda Nobunaga, ruler of the small but prosperous province of Owari. In 1570, he captured the capital of Kyoto and in just three years eliminated the Muromachi shogunate. Thanks to the protection of Christianity and the widespread use of firearms, Nobunaga managed to conquer the capital region of Kinki and Central Japan in 10 years. Gradually, he implemented a plan for the unification of the “Celestial Empire,” mercilessly suppressing secular and Buddhist centrifugal forces, restoring the authority of the imperial house and raising the economy destroyed by wars.

Help with student work on the topic of the Unification of Japan at the dawn of modern times

Coursework 440 ₽ Essay 230 ₽ Test paper 240 ₽

Get completed work or consultation with a specialist on your educational project Find out the cost

In 1582, Nobunaga died at the hands of his own general, without having time to realize all his plans. However, the unification course he took was continued by his talented subordinate, Toyotomi Hideyoshi. He crushed the opposition of the elders of the dead overlord and eliminated the independent clan states of the provincial rulers. In 1590, Japan was finally united by the forces of Hideyoshi, who began to rule the country alone. On his instructions, the All-Japan Land Cadastre was compiled, which eliminated the system of private estates and determined the level of land productivity. The land was transferred into the hands of the peasants, who had to pay taxes to the government in full accordance with this level. Hideyoshi also carried out a social reform that divided the population into military administrators and civilian subjects, with the confiscation of weapons from the latter. At the end of his life, Hideyoshi began a war with Korea and persecution of Christians, which cost his descendants power.

States of the East traditional society in the early modern era

States of the East: traditional society in the early modern era

Land tenure methods

Village community

Estates

Religion

For a long time you studied the history of Western countries, learned how society developed. Now you have to get acquainted with the features of the development of eastern states in the 16th–17th centuries.

During the lesson, you will learn what influenced the worldview of the inhabitants of India, China and Japan, how economic and social relations developed in these states.

Let's start looking at the countries of the East with methods of land ownership

, characteristic of these states.

India.

In eastern countries, the main owner of all lands was the state. In India, all conquered territories became part of the land fund, from which allotments were distributed; they were called jagirs

.

However, the plots remained in state ownership. Their holder - the jagirdar

- was temporary and did not have the right to transfer the land by inheritance. As a rule, jagirdars owned several tens of thousands of hectares, part of the income from which was used to maintain military detachments. The jagirdar did not use one plot of land throughout his life. After a certain number of years, he was given a new plot of land, where he again had to build a farm.

There was also private ownership of land. This right was used by conquered princes who paid tribute, sheikhs who had small estates and later Muslim theologians. The use of land was monitored by a special department - the divan

.

China.

In China, lands were divided into state and “people's” (private).

The government included

· lands confiscated from criminals;

· pastures;

· lands of the imperial house;

· lands granted to officials, princes, temples;

· areas belonging to military settlements.

All other lands were private; both feudal lords and peasants could own them. There were frequent seizures by the nobility of territories owned by peasants.

There were " job fields"

"- these are state lands that were provided to officials for the duration of their service.

There were also “ fields for maintaining disinterestedness

”, they were received by officials who had poor wages, and so that they did not take bribes, they were provided with lands that provided income. Most of the peasants used the land on a lease basis.

Japan.

In Japan, all land was owned by the state. Both peasants and feudal lords received plots for temporary use. The size of a peasant's plot depended on the number of people in the family, and for a feudal lord - on the nobility. The land could be confiscated at any moment. This system helped strengthen the central government.

Village community.

The bulk of the population of the eastern states was employed in agriculture, where the village community remained fairly strong. Let's find out what were the features of its organization in China, India and Japan.

India.

In India the community was very strong. Land holdings did not belong to individuals, but to communities, within which plots were already distributed to families. Forests, pastures, and wastelands remained in collective use. Each community paid a certain amount of tax to the state for the right to use the land. This made it easier for the state to collect taxes. The community was governed by a council consisting of the 5 wealthiest residents.

In addition to farming, community members could engage in crafts. However, the residents of the community were required to support several professional artisans who served the needs for clothing and household items.

All positions within the community were clearly distributed and inherited. It turned out that while remaining free, a resident of the community could not leave it, because he had the right to do anything only in his community. Outside of it he became an alien

and lost his rights. The newcomers did not have the right to vote; they could only have land on a lease basis, receiving 1/8 of the harvest. Craftsmen were also disenfranchised.

China.

In China, a village community consisted of 100 households, divided into groups of 10 households. At the head of the entire community was the elder

, and groups of households were headed by

tens

, who were chosen among those who had reached 50 years of age and were distinguished by impeccable behavior.

The task of the tens was to control the collection of taxes. Officials were prohibited from appearing in communities for this purpose under penalty of death. The tens also monitored the behavior of the community residents and reported any violations to the ruler.

There was mutual responsibility in the Chinese community. In case of non-payment of taxes or refusal to perform duties by one of the residents of the community, his work was transferred to other residents. This made it easier to collect taxes and control the flow of funds into the treasury.

Japan.

In Japan, the village community had become significantly stronger by the 15th century; it had a fairly large share of self-government. The main goal for the community residents was to reduce taxes and abolish labor duties. The community took upon itself the obligation to control the payment of taxes by its residents, in return it received the right to manage internal affairs and independently dispose of excess products. Community leadership

· held the general meeting;

· was involved in water distribution;

· decided how to use the land;

· divided labor duties among residents.

Only those peasants who owned land had the right to vote at the meeting. In this way, the community reduced the interference of imperial officials and the plunder of peasants.

Estates.

One of the main features of traditional societies of Eastern countries was a clear division into classes. Everyone led life as the rules and class affiliation prescribed for him.

India.

In India

society was divided into

4 varnas

: brahmanas, kshatriyas, vaishyas, sudras. Each varna included many castes, more than two thousand in total, many of which have survived to this day. Let us take a closer look at the varnas of Indian traditional society.

Brahmins

- this is the highest varna, it can be compared with the European clergy. Brahmins performed the duties of clerks, priests, teachers, judges and officials.

The second stage was occupied by kshatriyas

. This was the military class. From childhood they were raised to be strong and courageous, ready to defend the state. The main goal of the kshatriyas was to control the observance of order and law. Only they were given the right to kill those whose behavior did not comply with the rules of varna. Rulers were usually chosen from among the kshatriyas.

Vaishya

- This is the third rung of the social ladder of Indian society, including traders, moneylenders and artisans.

On the fourth stage are the sudras

. These are farmers and servants. Their main occupation is cultivation of land and cattle breeding, as well as serving the three highest varnas. In modern India, this is the largest group of the population.

Outside the social ladder in India were the " untouchables"

" These were people who cleaned the streets of garbage, worked with animal skin and clay, and did laundry. They settled far from other residents and did not have the right to visit temples. It was believed that they could defile representatives of the varnas.

China.

In China, society was divided into privileged and unprivileged sections.

The first included relatives of the imperial family and nobles who had titles. A distinctive feature of Chinese society was the existence of such a class as the Shenshi .

, these were people who passed the exam to qualify for public office. They were scientists and were universally respected. It is important that representatives of unprivileged classes, which included landowners, peasants, traders and artisans, also had the right to take the exam for the title of shenshi. The lowest class in China were people who did not pay taxes - slaves, artists, monks, servants, executioners.

Japan.

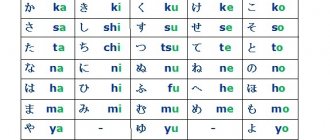

In Japan, the class structure developed into the scheme SI-NO-KO-SHO

.

Or warriors ,

peasants, artisans and traders. Above all classes was the emperor, who was deified, and the clan nobility.

The highest class were the samurai

.

These are representatives of the Japanese nobility, whose main task was military service. During wars between feudal lords, detachments of samurai were formed, on whose skills the outcome of the war depended. The samurai had their own code by which they lived - “ Bushido

”, or the way of the warrior.

It provided for loyalty to the master, modesty, politeness, and the ability to sacrifice oneself. In the event of the death of his master, the samurai performed “ sepukku

,” a ritual ripping open of the abdomen.

Please note that peasants

occupied the second rung of the social ladder. They were respected because they provided food for the samurai and the emperor. However, their life was defined within very strict limits. Peasants did not have the right to eat rice or bake cakes from it; this was considered a great waste, since rice at that time was synonymous with wealth. Clothes were worn only from linen or cotton.

All artisans

were united into workshops. The choice of craft was guided by heredity. If the father was engaged in making clothes, then his children will do it too. Craftsmen were divided into three categories:

· those who had their own store;

· those who performed work on site;

· traveling artisans.

Merchants

were a source of enrichment for the imperial house, and therefore enjoyed greater freedom. They had their own charter; merchants were forbidden to gamble, write poetry, or learn the art of quick drawing and swordplay. All this could distract from immediate work.

Religion.

To better understand the events of subsequent years, it is necessary to know about the worldview of the inhabitants of the East. It was formed under the influence of three religions - Confucianism, Buddhism and Shintoism. Let's consider their main provisions.

Confucianism

formed in China, and was a mandatory teaching for all its inhabitants. It had a significant impact on the behavior and formation of the worldview of the Chinese.

Confucius taught: “ The state is a big family, and the family is a small state.”

" It is necessary to honor your parents and elders, the same respect must be shown to the emperor, since he is the head of a large family-state.

One of the central ideas in Chinese culture is the following: “ To achieve equality, you need inequality.”

" Relations in society have been built on this for many centuries.

The teaching itself was based on 5 principles:

· love for people, it was his authorship that belongs to the rule “ Do not do to a person what you do not wish for yourself”

»;

· justice;

· performance of rituals;

· prudence;

· sincerity.

Every resident of China had to comply with them.

Buddhism became widespread in India, China and Japan

. This religion also determined the basic principles of life characteristic of Eastern people. The Buddha taught that a person’s entire life is suffering, which arises from the fact that a person constantly strives to fulfill his desires. When he does not achieve this, he takes the path of suffering. To prevent this from happening, you should do the following:

· believe that the world is full of suffering;

· limit your desires and aspirations;

· speak only the truth and kind words;

· do good deeds;

· do not harm living things;

· monitor your thoughts, drive away bad ones and think about good things.

If a person constantly improves, then in his next life he will be reborn.

e and he can become a representative of the highest caste.

Shintoism became the national religion in Japan

.

This is an ancient religion, but Japanese rulers returned to it in the 18th century, when there was a need to strengthen the power of the emperor. According to the doctrine, there is a sun goddess Amaterasu

. The Emperor is her direct descendant and representative. Through it, people can contact the goddess. A distinctive feature of Shintoism was the absence of a teacher who would explain its essence.

Thus, let's compare the three eastern states according to the indicators that we have considered. In India and Japan, all land was state-owned; in China, there were both state and “people’s” lands. The village community had self-government everywhere. Estates in India were represented by four varnas: Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas and Shudras; in China there were privileged and unprivileged classes, in Japan there were classes of warriors, peasants, artisans and traders. The main religions were: Buddhism in India, Confucianism in China, Shintoism in Japan.

Oda Nobunaga

Definition 2

Oda Nobunaga (June 23, 1534 - June 21, 1582) was a military-political Japanese leader during the Sengoku period, one of the most prominent samurai in Japanese history, who dedicated his life to the unification of the country.

Need advice from a teacher in this subject area? Ask a question to the teacher and get an answer in 15 minutes! Ask a Question

Oda Nobunaga began the unification of Japan in 1568. His army occupied the Japanese capital of Kyoto with the aim of punishing the murderers of the former shogun Ashikaga Yoshitera. With the participation of Nobunaga, the younger brother of the deceased, Yoshiaki, was proclaimed the new shogun. In honor of the event, Nobunaga ordered the construction of Nijo Castle for the new shogun. Demonstrating loyalty to the shogun, he personally supervised the construction of the castle, thereby strengthening his own influence.

In 1573, Oda Nobunaga put an end to the reign of the Ashikaga shogun, eliminating the shogunate as a system of government. This ended the 200-year Muromachi period. Nobunaga increased the authority of the imperial court under his control. He built a castle in Azuchi, which became his residence and gave its name to the period in Japanese history.

By that time, he had subjugated almost all of central Japan, but the desire to create a centralized state faced opposition from two feudal houses - Mori in the west and Takeda in the east. There was also a third enemy - Buddhist monasteries.

Monasteries in Japan were not just religious centers, but also major military and economic centers. The real state within a state was the impregnable Enryakuji monastery of the Tendai sect on Mount Hiei in the vicinity of Kyoto. Thousands of buildings, a huge number of monks and an army. The largest religious, cultural and economic center was the Honganji Temple of the Shinshu sect in Settsu Province. It took Nobunage two years to capture Enryakuji, and the Honganji Temple monastery resisted him for 11 years. Everything was destroyed by fire and sword: repositories of ancient manuscripts and books, unique valuables, warehouses, residential buildings and craft districts.

At the same time, the main battles of the Tokugawa and Takeda armies were unfolding in the east of the country. After the death of the head of the dynasty, Takeda Shingen, his son Katsuyori wanted to become the strongest daimyo in the country. In 1575, the combined forces of Nobunaga and Tokugawa inflicted a crushing defeat on Katsuyori's troops at the Battle of Nagashino. In this battle, Nobunaga's troops made extensive use of firearms for the first time.

After the victory, preparations began for the next campaign. The new enemy was Mori Terumoto, the largest Japanese feudal lord. His possessions occupied the western part of the island. Honshu and accounted for one sixth of the entire territory of the country. Oda Nobunaga did not have time to defeat him. As a result of the betrayal of one of his vassals, he died in 1582.

Reforms 60-80 XIX century (Meiji Reforms)

Bourgeois revolution of 1867-68. opened a new historical period in the life of Japan. The deep crisis of the feudal system, the aggravation of the class struggle, the threat of colonial expansion and the need, in this regard, to strengthen the country's economy forced the new government of Japan to take the path of political and socio-economic reforms. The intentions of the reformers were outlined during the civil war in 1868 in the emperor’s oath to convene a “broad assembly” and decide all state affairs “in accordance with public opinion.” The entire people were promised permission to “carry out their own aspirations and develop their own activities.” The statement also defined the way out of the crisis: “Knowledge will be borrowed from all over the world and in this way the foundations of the empire will be strengthened.”

The reform program began to be implemented immediately after the overthrow of the shogunate, affecting the main spheres of life of Japanese society.

In the socio-economic sphere, reforms began with the law of 1867, which abolished the monopoly of craft guilds and merchant guilds. Internal customs barriers between individual principalities were eliminated, which created conditions for the formation of a single internal market.

In 1871, the feudal system of class division of society was abolished, equality of all classes before the law, freedom of choice of profession and place of residence were proclaimed. In 1872, a unified monetary system was introduced. But the most significant transformation in the socio-economic sphere was the agrarian reform, legislatively formalized by a number of acts of 1871-1873. Its essence was as follows. Large feudal landownership was abolished. The state bought the land holdings of the feudal nobility on conditions favorable to the landowner - he was paid a lifetime cash pension, approximately equal to 10% of the previous gross income from the holdings. Private ownership of land was affirmed: the purchase and sale of land was allowed and a land census was carried out, during which the land was transferred into the ownership of those who actually cultivated it.

All feudal taxes and duties were abolished and an annual cash tax (3% of the value of land) levied by the central government was introduced.

There was no radical redistribution of land (a certain mass of peasants remained land-poor and landless), but nevertheless the agrarian reform of 1871-1873. contributed to the establishment of capitalist relations in the countryside.

Important transformations also affected the state. The army, the state apparatus, and the administrative and territorial structure of Japan were subject to reform.

In the early 70s, using foreign experience, the authorities began to reorganize the armed forces. The German experience became decisive in the creation of the ground forces, and the English one in the formation of the navy. In 1872, universal conscription was introduced. The samurai lost their exclusive position as warriors, but they were retained the privileged right to occupy officer positions.

In 1871-1878. The administrative-territorial structure and local self-government of Japan have changed. The division into principalities was eliminated, and smaller administrative-territorial units were introduced - prefectures with approximately equal populations. The administration of the prefecture was entrusted to a governor appointed by and accountable to the central government. In 1878 Advisory bodies are created under the governor - elected assemblies and prefectural councils.

In 1885, a new, previously unknown body appeared in the Japanese government apparatus - the cabinet of ministers, which marked the beginning of the development of a sectoral management system.

Reforms of the 60-80s. XIX century led to the centralization of the country and created favorable conditions for the development of capitalism. An important consequence of the reforms was the growth of political activity in Japanese society, which manifested itself in the emergence of political parties.

The first political parties, liberal in color, appeared in Japan in 1881-1882.

The noble wing of the liberal opposition in 1881 created the Jiyuto Party, which was also supported by a significant part of the peasantry. The Jiyuto Liberal Party advocated a reduction in land taxes and against the monopolization of state power by the “clan” bureaucracy.

The bourgeois wing of the liberal opposition in 1882 founded the Kaishinto Party, a reform party that demanded from the government measures aimed at accelerating the rate of industrial growth, speedily revising unequal treaties, promoting exports, and intensifying foreign policy.

The fundamental program demands of both parties were very similar: they advocated the introduction of a parliamentary system while maintaining the monarchy.