Download the large encyclopedia of Japan from A to Z with multimedia:

HEYAN - the historical period from 794 to 1185, named after the location of the imperial court in the city of Heian (kyo) (Kyoto).

During the reign of Emperor Kammu (781–806), the imperial court sought to escape from the oppressive influence of large Buddhist monasteries and temples, which were built in large numbers around Nara and rather strictly regulated the life of the capital. In 784, by decree of the emperor, the capital was moved from Nara to Nagaoka, in the province of Yamashiro (present-day Kyoto Prefecture). Responsibility for the construction of the new capital was entrusted to Tanetsugu, a representative of the influential Fujiwara family close to the throne. But a few months later Tanetsugu was killed. One of the results of the massacre was the supreme decision to abandon the desecrated Nagaoka and move the court to a new location. The imperial treasury was empty, it was depleted by constant campaigns of conquest, so new construction began only under Emperor Saga, who inherited the throne after the death of Kammu.

A location was chosen for the capital in the valley of the Kamo and Katsura rivers, which connected the planned city with the busy sea bay of Naniwa (in the future - Osaka). Initially, the city was named Heian (kyo) - “Capital of Peace and Tranquility.” Only many years later it began to be called Kyoto (Capital City). As for Nara, the urban planning model and prototype of the new Japanese capital was Chinese Chang'an with a rectangular grid of streets stretching strictly from south to north and from east to west. The size of the city (4.4 km x 5.2 km) was slightly larger than that of Nara. The northern part of the city area was dominated by the Great Imperial Palace, surrounded by government buildings (there were more than seventy of them) and the houses of senior courtiers. The estates of the nobility occupied an entire block (1.5 hectares), while commoners were allocated 1/32 of the block for housing construction.

All the most important posts in the state became hereditary and were assigned mainly to Fujiwara. The previous system of promotion after passing the relevant exams, borrowed from China, was abolished. In addition, it became a tradition for emperors to marry maidens of the Fujiwara clan and to appoint crown princes exclusively from the imperial heirs along this line. Therefore, all the sovereigns of the Heian era had Fujiwara in the role of grandfathers, uncles, cousins, brothers-in-law, as well as regents, chancellors and simply mentors. From the end of the 10th century. Japanese emperors accepted the throne or abdicated solely at the behest of Fujiwara. This unlimited power was passed from hand to hand within one clan - from the outgoing head to the new leader - until the middle of the 12th century.

True, the imperial family of Sumeragi sought to defend at least the crumbs of their independence. For this purpose, at the end of the 10th century. The institution of curando was established - a personal secretariat under the emperor, which in some cases made it possible to act bypassing the state apparatus, which was entirely subordinate to Fujiwara. This was, in essence, the first step towards the dual power that later became established in the country.

But the confrontation between the emperors and Fujiwara took on even more bizarre forms in the 11th century, when the insei system - monastic rule - was created. In an effort to escape from under the heavy hand of Fujiwara, the emperor voluntarily abdicated the throne in favor of the heir, and, having accepted monastic rank, he seemed to be moving away from the world. However, in reality, the emperor-monk had his own court, his own staff of courtiers, palace guards and other attributes of power. From his monastic cell, he tried to govern the state in his own way, fighting with the Fujiwara clan for key positions in the government, for new lands, estates, and, consequently, income. The insei system made it possible to gradually weaken the dominance of the Fujiwara clan.

The government structure of Japan at that time was borrowed from medieval China. The main powers of power were concentrated in the hands of the left minister and the right minister who replaced him during his absence. Accordingly, there were left and right audit offices, which, in turn, were subordinate to various departments - ceremonial, tax, military, judicial; chambers - music, sciences and education, embassies and monasteries; management - financial, cavalry, navy, construction, hunting, kitchen, imperial tombs, incense, wine, imperial pedigree, dark and light principles (fortune-spell); departments - supervision of the protection of palace gates, palace decoration, sewing, weaving, lacquerware, prisons, etc.

Meanwhile, the state machine was malfunctioning. Officials were much more interested in new appointments at court than in the practical tasks of governing the country. Many business procedures were simplified or even ignored. All important matters were decided by the chancellor with an adult emperor or the regent with a minor. The Heian period (794–1185) is sometimes referred to as a time of aristocratic rule. But we should not lose sight of the fact that most of the aristocrats of that time belonged to the Fujiwara clan.

Under Fujiwara's rule, serious social changes took place in Japanese society. Even during the Nara period (710–794), the government, due to the constant shortage of state lands, carried out a number of serious projects to introduce new plots into circulation. For this purpose, any efforts of private individuals were supported. As a result, large plots of land were concentrated in the hands of monasteries, churches, and the nobility, which were cultivated by tenants. During the early Heian period, the size of cultivable land owned by the imperial family increased significantly. Thus, the basic principle of the Taika reforms (645) on state ownership of all agricultural land and the allocation of equal plots to all peasants for each family member on a 5-year lease has lost practical significance.

But the increase in cultivated land did not lead to enrichment of the state treasury. Large feudal lords evaded paying taxes, preferring to spend the money and products collected from the peasants for their own needs. The tax from the capitation system was transferred to a share of the harvest. Among the peasantry, a significant group of large farmers stood out, who formally registered land in the name of local feudal lords - princes or monasteries, paid them taxes lower than those required by the state, and they, in turn, provided them with protection, including sheltering them from state tax collectors.

Ruthlessly robbed by the state and local feudal lords, the peasants were starving. And the imperial court needed more and more money for entertainment and celebrations. The Heian period was a time of mass exodus of peasants from their plots. They fled inland, to the north, hoping to find new free land there for cultivation and become free landowners. The flight of peasants acquired such proportions that villages became depopulated, as during epidemics, public lands turned into wastelands. The emperor time after time sent troops to the northeast to rein in the rebellious Ainu “barbarian” tribes, push them further north, and at the same time catch runaway peasants and expand the country’s territory by annexing the lands they had developed.

Meanwhile, the imperial court lived its own separate life. The number of aristocratic families close to the court was not so large - no more than twenty. Other, less noble families were grouped around them. There was also a provincial aristocracy led by appointed provincial governors, but they most often preferred to remain at court, sending their assistants in their place. The capital of Heian was considered the only place worthy of a noble person.

At the end of the 10th century. The imperial palace, ceasing to be the place where state affairs were carried out, became the center of prosperity for all types of arts. Outstanding poets and musicians gathered in the chambers decorated with works of the best artists and calligraphers. In the life of the court, magnificent ceremonies, festivals, poetry and music tournaments, games, and competitions occupied a large place. Many games were borrowed from China and required excellent knowledge of Chinese culture and poetry.

These requirements determined the entire system of court education, which was also entirely borrowed from China. The main educational institution for the children of the aristocracy was the Chamber of Sciences, which was directly subordinate to the Ceremonial Department and had four departments: Chinese classics, history and literature, law, and mathematics. A young man from a noble family had to know by heart the main works of Confucian classics and the works of Chinese historians. Participation in palace ceremonies and entertainment also required the ability to compose poetry in Chinese, play several musical instruments, and sometimes paint a fan or screen in the Chinese or Japanese style. The aesthetics of fashion at that time dictated not only strict adherence to all the intricate rules of etiquette, but also such “little things” as, say, the shade of writing paper, the smell of perfume, incense, the cut and color of a dress depending on the class of the official, etc. This knowledge (in addition to family connections) was a prerequisite for advancement through the ranks. Despite the powerful influence of Buddhism, Heian society was style-oriented rather than moral, and appearance was more important than virtue.

The requirements for aristocratic women were simpler. Moreover, most often they were removed from direct participation in public life. However, the wives and concubines of the emperor and senior government officials (polygamy was common in Japan during the Heian era) had great influence, and pleasing them was one of the main activities of many courtiers. Lyrical correspondence with the lady of the heart became widespread.

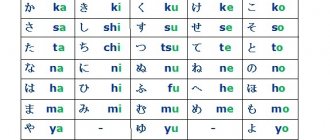

The Japanese kana syllabary owes its appearance largely to this correspondence and to the weaker knowledge of the court beauties in Chinese hieroglyphs. It made it possible to transfer writing to a national basis and gave a powerful impetus to the emergence of Japanese literature. The works of court poets and writers Murasaki Shikibu (“The Tale of Genji”), Sei Shonagon (“Notes at the Bedside”), and Aritsuna (“The Diary of a Mayfly”) became masterpieces that have not lost their worldwide value to this day.

In the 10th century In Japan, the process of assimilating and rethinking the culture borrowed from China is ending. From the end of the 9th century. The isolation of Japan from mainland influence began, which lasted for three centuries. Protected from external influences and confined within the narrow confines of court life, the Heian aristocrats, building on the centuries-old cultural traditions of China and Korea, created their own unique culture, which became the basis for the cultural development of future generations. In painting, the national Yamato-e style gradually gained great popularity, the character of Buddhist sculpture and architecture changed, and ancient folk songs performed according to the canons of Gagaku music came into fashion. Cultural skills imported from China, having gone through a process of creative development and fermentation on Japanese soil, melted into something unique and purely national.

While the Western world was in the darkness of barbarism and ignorance, high culture, a spirit of chivalry and nobility reigned in Japan. And this was long before the advent of the Renaissance in Europe! The cult of beauty that reigned in Heian fostered a society of great charm and elegance. Despite the geographical, historical and social limitations of this phenomenon, it took its place in the development of universal human culture. And to this day, Kyoto, the once magnificent Heian, is considered the cradle of Japanese culture, the main cultural center of Japan.

Buddhism and culture

Buddhism also plays an important role in the development of culture. Buddhism was adopted by the rulers and officials of Japan as a continental religion. Huge amounts of money were spent on the construction and decoration of luxurious temples and huge Buddha statues, a large number of people were involved in their construction, at that time it was considered an expression of faith.

As a result, such a policy of instilling Buddhism, its values and traditions led to the fact that a culture accompanying Buddhism began to penetrate into Japanese culture.

At this time, they began to build majestic temples and monasteries, which mainly belonged to different sects, contributed to their demarcation, which led to the choice of one direction of teaching. The most powerful and influential in the 9th-10th centuries in Japan were the Shingon sects, which emphasized preaching to a narrow circle of initiates and worshiped shrines hidden from others, and performed mystical rituals.

The influence of Buddhist sects greatly influenced the consciousness of people and, oddly enough, the architecture of the country. The shape of monasteries and temples changed, the spacious layout, its clarity and clarity began to disappear. Temples of esoteric sects were built, as a rule, in secluded places, often among the mountains, they were small in size, the location of the buildings was subordinate to the terrain and connected with nature.

Are you an expert in this subject area? We invite you to become the author of the Directory Working Conditions

In the 9th century, the first schools of Buddhists appeared. In 806, the Tendai school was founded by the monk Saita; in 816, the monk Kukai founded the Shingon school. Common to all schools was the idea of the primordial presence of Buddha nature in all beings, so under the influence of the Tendai school the concept of kami deities as incarnations of Buddha appears. In the second half of the 11th century, the cult of Amida Buddha grew in popularity. His followers believe that for salvation and rebirth on heavenly earth it is enough just to repeat the name of the Buddha himself.

At the end of the 10th century, the emperor's palace ceased to be the center of politics and became the center of the prosperity of Japanese culture; the emperor's chambers began to be decorated with the highest works of art. Holidays and celebrations were often held, where the most outstanding poets of that period were invited, often musical and poetic competitions took place among them, various games that were borrowed from the Chinese, and accordingly required a good knowledge of the poetry and culture of China.