Boy

The 15-year-old student doted on his grandparents, his parents said, making the killing of his grandfather and the stabbing of his grandmother on October 18, 2021, even more mysterious.

However, when he was arrested the next day, everything became much clearer. Although no less terrible.

The boy, who was not identified by authorities because he is a minor, told police he went to his grandparents' house in Saitama Prefecture, north of Tokyo, to kill them because he didn't want them to be ashamed of he planned to do later. The boy was planning to go to his school and kill a classmate.

Schoolgirl sues government for forcing her to dye her hair

A classmate, according to the boy, bullied him at school, and the boy “could not forgive him.”

The boy's grandparents have become extras in a crisis that has long plagued Japanese schools but is becoming increasingly acute, a new study shows.

Girl

Rising suicide rates among children in Japan. Causes

Nanae Munemasa was in elementary school (ages 6-12) when the bullying began.

A 17-year-old schoolgirl recalls that boys beat her with broomsticks, harassed her in the girls' restroom and even attacked her during a swimming lesson. “I was the last one out of the pool,” she said. “A fist came out of nowhere and hit me in the face. I went under water and almost drowned. I had a huge bump on my forehead." “A long break from school allows you to stay home, so it's a haven for those who are bullied,” Nanae said. “When the summer ends, you must return. And once you start worrying about being bullied again, it can be a step towards suicide.” As the bullying intensified, Nanae began skipping school and contemplated suicide, but did not go through with it.

Eventually, Nanae decided to stop going to school and stayed home for almost a year. Nanae's mother, Mina Munemasa, supported her daughter's decision.

Record

A report released by Japan's Ministry of Education on October 25, 2021 shows that bullying incidents in schools have reached record levels. And the real figure is likely to be even higher, experts warn, as many children are too scared to come forward and denounce their tormentors.

Serial fetishist arrested for stealing whistles from little girls

Reported cases of bullying in private and public schools across Japan , from elementary school to senior high schools, reached 414,378 in the school year through March 31, 2018. This figure has risen sharply from the previous year, increasing by more than 91,000 cases. The report said 3,511 students were arrested or taken into custody for bullying, more than double the number in 2017.

A total of 474 cases were classified as "extremely serious", an increase of 78 cases on the previous year, and 55 were classified as involving "life-threatening harm". Authorities were able to determine that of the 332 students who committed suicide during the school year, 35 children had been bullied at school (based on post-mortem notes).

Suicides

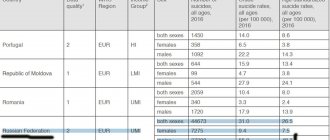

Japan has one of the highest suicide rates. A report from the World Health Organization shows that it is actually 60 percent higher than the global average and the rate of child suicide continues to rise despite the decline in overall suicide rates.

According to research by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, 332 Japanese elementary, middle and high school students died by suicide in 2021. This was a 33% increase from the previous year and the highest since 1988, when the data was first calculated using the current method. This figure included 227 high school students, 100 high school students and 5 elementary school students, with suicide rates among high school students up 42% year on year. Of the 332 schoolchildren, 193 were boys and 139 were girls.

“Japan has always had a problem with bullying in schools, but I think there's been a lot more kids committing suicide that has been linked to bullying, and I think that's made the problem more serious for schools, for education authorities and the government.” , said Mieko Nakabayashi, a professor at the School of Social Research at Waseda University.

“They are under much more pressure now than before.” “These cases are becoming increasingly documented and reported, which may explain the increase in the number of cases, but it is clear that more efforts need to be made to address this problem.”

Children of suicide.

The main causes of child suicide are problems related to school, such as excessive demands of the school curriculum or bullying. These problems lead children to depression. Kenzo Denda, a professor at Hokkaido University, reports that in Japan, one in twelve elementary school students and one in four middle school students suffer from depression, which causes many of them to commit suicide .

We see a spike in suicides in September as children return to school after the summer holidays. Japanese children are more likely to commit suicide on September 1st and 2nd than on any other day. The spike in suicides repeats in April as students return to school to start the new school year ( Kenzo Denda ). Problems related to school and children's suicidal tendencies are actually part of Japanese culture.

Compared to Westerners, Japanese are more likely to commit suicide when faced with a difficult situation. In Japan, suicide has a different meaning and is not perceived in the same way as in the West. Unlike Christian countries, in Japan suicide is not considered a sin. This is seen as a way to take responsibility and ask for forgiveness. Suicide has deep roots in the country's history; we can think of samurai who performed seppuku to clear their name, or kamikaze pilots during World War II

Since 2012, Japan has taken the issue of suicide seriously, and the government has taken measures aimed at reducing the suicide rate by 20% by 2025. A number of prefectural education authorities have taken measures to eradicate the problem among children, including mandatory surveys after each semester for all students on bullying and additional staff meetings to address situations once an incident is confirmed.

Racial discrimination against half-breeds in Japan.

Japan. Bullying at School. Suicides of schoolchildren

At first glance, Japan is a quite prosperous country with a developed economy and socio-cultural sphere. But as it turns out, not everything is so rosy. The population of this country has its own serious problems.

One such problem is the problem of suicide. And the worst thing is that not only adults commit suicide. Many school-aged children commit suicide. The suicide rate among Japanese children is the highest in the world.

The main reason for childhood suicide is the Japanese education system and society. Children are brought up on the principles of collectivism, that you need to be like everyone else, you cannot stand out from the crowd, and an individual in society means nothing.

There are, of course, people who think differently. But such people are in the minority. And they cannot single-handedly influence society as a whole. Some already in childhood “break down” under the pressure of such a system and commit suicide. In Japanese media every 2 —

For 3 days, information has been appearing about suicides of schoolchildren.

The main problem of Japanese society remains the problem of school bullying. It may sound strange to hear, but bullying is the norm in Japanese schools. There are several types:

- children bully a child who studies in the same class with them;

- teachers bully children they don’t like;

- older students bully younger ones.

Child cruelty knows no bounds. There was a case in one of the prefectures of Japan. The boy studied at a regular school. The guy was modest and became an object of ridicule for his classmates. They beat him, forced him to eat dirt, and spat in his food. Then it got even worse: they strangled him and hung him out the window. The child was pushed in every possible way to commit suicide, repeating that no one needed him. This “pressure” continued for a week. As a result, the boy could not stand the bullying and rushed 14 —

th floor. The perpetrators of this incident suffered absolutely no punishment. There are a lot of similar cases happening in Japan.

If a child is in any way different from the crowd, then he will definitely be ridiculed. If he is taller, shorter, fatter, thinner than others, that means they will bully him. More beautiful, smarter, stupider - the same thing.

One Japanese school teacher said that he was also bullied by his classmates for having curly hair. But when he became friends with a guy who was a member of the local judo club and had a height of about 2

meters, the bullying soon stopped.

During bullying, they not only damage property or beat them, but also force them to eat wasps, drink urine, strip them and push them out into the street, and lock them in a classroom.

There is another type of bullying - ignoring. The person is completely ignored, perceived as empty space. Usually this boycott is carried out by the entire class. After all, if someone stands up for the victim, he will also be subject to ridicule.

All this leads to children committing suicide. They jump from a window or roof of a building. They often throw themselves from the roof of their own school.

Teachers very often bully their students. The teacher may not like the child's appearance or intellectual abilities. There was a case in 2013

d. The physical education teacher mocked one student.

He believed that thanks to this the child would become morally stronger and achieve great success in sports. He shouted at the guy, hit him with a ruler, and pushed him to the floor. As a result, a 17 -

year-old schoolboy jumped out of the school toilet window.

Such cases are not uncommon in Japan. Almost every class has its own “punching ball” - a child who is mocked and humiliated.

All this bullying is a huge problem in Japanese society. Through bullying, children try to fight against those who are different from the general mass. But adults also practice this: ignoring them, setting them up at work, etc.

Previously, children who had mixed blood were also bullied. But now, in large cities, children with mixed blood are not uncommon. And very often they become leaders in the class.

At least little by little, the situation is beginning to change. The Japanese learn more about other countries and try to become at least a little friendlier. I would like to hope that this trend will continue and school bullying will simply disappear.

Humiliation culture

Still , a culture of humiliating those who are different is deeply ingrained in children in many societies, Nakabayashi explains, although she agrees that Japan has some unique characteristics.

Group culture is important in Japan. This practice means that everyone must be part of the group, follow the rules and have the same opinions as other members. This means that every person who is different or does not follow the rules will be excluded and become a target for bullies. This is also the reason why some people look but don't react; if you are not one of the bullies, you may become the next victim. This also applies to teachers who sometimes know what's going on but turn a blind eye or even engage in bullying to get out of trouble.

Group culture is also associated with school pressure, as students are always expected to perform well and achieve the highest grades, and those who struggle do not receive any support, they just have to go along with the rest of the class. This aspect of Japanese culture may explain, at least in part, the problems children encounter in school that may lead them to want to end their lives.

In Japan you have to fit in with other people. And if you can't do that, you're either ignored or bullied.

+

The problem is compounded by a culture that dictates that going to school is the only option. “It's hell for kids who know they're going to be bullied at school but have no choice but to go,” she said. Schools “put the team first. Children who do not get along in groups suffer

Text of the book “To Beat or Not to Beat?”

Corporal punishment in Japan. Interlude

Traditional Japanese education, based on the principles of Confucianism, was very harsh (Mikhailova, 1988).

The famous Japanese scientist of the 17th century. Yamaga Soko said that as soon as learning begins to bring pleasure, its purpose is distorted because the desire for self-improvement disappears. This is the complete opposite of the opinion of Western European enlighteners, in particular Locke. However, the Japanese canon of man, with its exaggerated sense of shame and the idea of the plurality of “I,” encourages the educator to be careful. “For Japanese teachers and parents, “educating” does not mean scolding for something that has already been done badly, but, on the contrary, anticipating this bad behavior, teaching correct behavior. Even in a situation that clearly requires, if not punishment, then at least a reprimand, the teacher avoids direct condemnation, leaving the child the opportunity to “not lose face.” Bad behavior is not identified with the child’s personality; he is instilled with the belief that he, of course, can control his behavior, if only he makes an effort. Instead of discipline and reprimand, children are taught specific behavioral skills.

Teachers do not set the task of ensuring that children’s behavior meets the final requirements at every moment. Attention is paid only to ensuring that children, in the process of solving everyday problems, learn to distinguish the “correct” moral position from the “wrong” one. It is believed that excessive pressure aimed at momentary compliance with the norm can give the opposite result” (Nanivskaya, 1983).

Judging by the descriptions of specialists (I read a lot of scientific literature, including the latest, on this issue, and also consulted with major Russian scientists - anthropologist S. A. Arutyunov, historian and religious scholar L. S. Vasiliev and historian of pedagogy A. N. Dzhurinsky), such a cult of corporal punishment as in Christian Europe has never existed in Japan. However, corporal punishment (taibatsu) is widely represented in Japanese educational theory and practice (Miller, 2009). Japanese scholars translate this word as “guidance,” “guidance,” “mentoring,” “coaching,” and “teaching.” As in other cultures and languages, the relationship between educational physical influence on a child and the simple application of physical force to him is interpreted ambiguously and is sometimes described in different words: taibatsu

– corporal punishment,

chokai

– disciplinary punishment,

gyakutai

– violence or

shitsuke

– training (Goodman, 2000).

In the Japanese family, three types of influence on children have long been used: corporal punishment, isolation and expulsion (Hendry, 2003). When the country began to seriously consider banning corporal punishment in the mid-1980s, one Japanese father wrote in a newspaper: “When training dogs and horses, they are rewarded when they behave correctly and beaten when they do not. The same should be done with children. Children are animals who are taught to be human.”

In Japanese schools, corporal punishment was legally prohibited earlier than in many Western countries, but it was not easy. The ban was first introduced back in 1879, but in 1885 it was lifted, restored in 1890, canceled again in 1900, and restored again in 1941. After World War II, in 1948, the Department of Justice finally banned hitting and spanking children, forcing them to kneel or sit in awkward positions for long periods of time, or preventing them from going to the bathroom or eating their own breakfast.

The school administration failed to fully implement these rules. The range of corporal punishment used by Japanese teachers is very diverse. 69% of teachers surveyed in 1986 named hitting with a stick or something similar, 63% - poking and shoving, 60% - punching, 59% - forcing a child to sit on his knees for a long time in an uncomfortable position ("seiza position") "), 54% - spanking, etc. Ten years later, the most common (named by 58% of respondents) form of taibatsu was spanking. Between 1990 and 1995, the average annual number of reported cases of corporal punishment in Japanese schools was between 700 and 1,000, and neither educators nor children considered the practice particularly harmful. In one survey, 80% of children said that their parents or teachers hit them, but 15% of them thought that the punishment was fair and only 25% felt that they were punished too harshly (Kobayashi et al., 1997).

According to a survey of six hundred mothers of 13-year-old schoolchildren conducted by the Benesse Corporation scientific and pedagogical center, only 44% of children were not subjected to corporal punishment during their years in primary school. The number of children punished increases with age, with boys being punished more often than girls. Children themselves react to corporal punishment ambiguously. Nearly half think the punishment they received was harsh or too harsh. Half of the schoolchildren are ready to accept or endure corporal punishment, but 30% of respondents disliked their teachers after this, and only 5% continue to love them. As for mothers, 50% consider the corporal punishment their child received deserved, 16% do not think so, and only 20% protested against the teacher’s illegal actions. 14% of mothers believed that punishment was an effective means of maintaining discipline, 68% approved of occasional punishment and only 17% condemned it under any circumstances. The percentage of fathers who approve of corporal punishment is significantly higher than that of mothers (50 versus 30). Many parents, who themselves do not like to punish their children, consider their educational methods to be too soft and even ask teachers to punish their children more severely.

In recent years, Japanese authorities have stepped up their crackdown on teachers who abuse their power. In 2005 alone, the Ministry of Education punished 447 teachers for this. But public opinion on this issue is divided. In an online survey in June 2008, 467 Club BBQ members (78% of them 30 to 50 years old) were asked, “Do you think there should be corporal punishment in school?” – 60% of men and 47% of women answered positively (21% and 16.5% responded negatively). 76% of surveyed men and 62.5% of women themselves were subjected to corporal punishment when they were schoolchildren, and flogged adults approve of corporal punishment twice as often, and condemn three times less often than non-flogged adults.

Many parents and teachers are frightened by the fact that in some schools violence from teachers is replaced by bullying from fellow students, and this bullying is extremely cruel. The number of registered teenage suicides on this basis increased from 14 in 1999 to 40 in 2005 (Dussich, Maekoya, 2007). Some authors associate this with the weakening of teacher power.

As for the Japanese family, corporal punishment remains legal in it. Comparative studies of Japanese, Canadian and American families show that the difference between them in this regard is not so much quantitative as qualitative. To find out how young people feel about corporal punishment and other discipline methods, as well as their own experiences with this area of life, 227 American and Japanese college students were asked to rate four different parenting scenarios. It turned out that the practical experience of corporal punishment among young Japanese and Americans is more or less the same: 86% of Japanese and 91% of Americans were subjected to corporal punishment. However, Americans were more likely than Japanese to be hit with any object, with American adults preferring to hit children on the buttocks and arms, and Japanese adults preferring to hit children on the head and face. In addition, young Japanese were more accurate than Americans in knowing exactly what offenses they were being punished for (Chang et al., 2007).

The main historical shifts in the Japanese, as in almost any other family, are associated with changes in paternal and maternal roles (Shwalb et al., 2010). The traditional image of a formidable father, whom the old Japanese proverb likened to an earthquake, thunder and lightning, clearly does not correspond to modern conditions. However, these changes relate more to normative images and attitudes than to the psychological traits of Japanese men.

According to the famous Japanese anthropologist Chiyo Nakane, traditional paternal authority was supported not so much by the personal qualities of the father as by his position as head of the family, while the actual distribution of family roles was always more or less individual and changeable. Today's culture recognizes and reinforces this fact, modifying traditional social stereotypes, rather than creating something new. By the way, the comparative coldness and presence of social distance in the child’s relationship with the father, often considered as evidence of a decline in paternal authority, are rather remnants of the mores of a traditional patriarchal family, in which they did not dare to approach the father and he himself was obliged to stay “on top.”

In 1969–1970 The answers of Japanese adults (13,631 fathers and 11,590 mothers) to the question of who is the main authority in the family - father or mother - were divided approximately equally. Other studies show that the mother's role in disciplining children, especially younger ones, is much greater than the father's; mothers are preferred by 65 to 73%, and fathers by 14 to 18% of adults surveyed. Nevertheless, fathers still seem stricter to children than mothers. This is a typical discrepancy between normative role expectations and actual behavior in Europe. Of 542 urban teenagers who responded in 1973 to the question: “Does your father tell you what kind of life you should lead now and in the future?” – only a quarter (25.4%) answered “yes”, almost three quarters (74.6%) of respondents said that they do not talk with their fathers about such things and do not follow their fathers’ advice. Over 12 thousand married couples in the mid-60s answered the following questions: “If a child does not listen, who do you think should reprimand him?”, “Who in your house actually does it in such a situation?” It turned out that this is expected from the father much more often (53.8%) than he actually does (30.8%), while with the mother the opposite is true (46.3% versus 36.3%). Although mothers are more likely than fathers to punish their children, the latter communicate (talk) much more intensively with them than with fathers (Wagatsuma, 1977).

How do Japanese parents achieve obedience? Maybe they resort to encouragement and praise more often than Europeans than to punishment or condemnation? No. According to the observations of J. Hendry (Hendry, 2003), Japanese mothers relatively rarely praise their children, and praise is rarely mentioned in pedagogy textbooks. Japanese parents, teachers and sports coaches are more likely to use criticism rather than praise. The child learns the comments made to him and tries not to repeat the mistakes made. However, unlike many Europeans, the Japanese try not to hurt the pride and dignity of students. It is not the child’s personality that is assessed, but his specific activity, level of competence, etc. In recent decades, this approach has become increasingly recognized in Western psychology.

A powerful means of disciplining Japanese children is also the ritualization of certain forms of behavior. It is common knowledge that the Japanese are obsessed with cleanliness. At the same time, there are few hired cleaners in Japanese schools and sports institutions. All this work is done by the guilty students, this serves both as punishment and teaching order. The same labor discipline exists in the family. In some ways this is reminiscent of the pedagogy of A. S. Makarenko.

Japanese children's perception of the social roles and behavior of their fathers and mothers today differs little from the ideas of Australian, English, North American and Swedish adolescents (Goldman J., Goldman R., 1983; Bankart S.P., Bankart V.M., 1985). This also applies to the distribution of punishments. A comparison of a representative sample of Japanese and American fathers and their teenage children showed that American fathers, in accordance with their media images, spend more time with their children than Japanese ones, but the assessment of fathers by Japanese children is less dependent on this factor; more subtle factors operate here. dependencies. When comparing a group of Canadian and Japanese families (Steinberg, Kruckman, Steinberg, 2000), Japanese fathers look more traditional: they are less likely to be present at births, take less time off, etc. However, they care for the child much more than the researchers expected .

In the 21st century these shifts are intensifying. Japanese advertising in 2010 stated that the traditional inattention of Japanese men to small children is becoming a thing of the past. According to the firm's survey, 73.4% of fathers of children under 12 are actively involved in raising them, and 86% of unmarried 20-year-old men plan to follow their example in the future. Dentsu named these new men Papa Danshi (Japanese fathers become “Papa Danshi”, 2010).

Of course, these shifts should not be exaggerated. According to a comparative international study (International comparative research on “home education”), the average Japanese father spends only about three hours with his children on a working day; only South Korean men spend less time with their children. Thai fathers spend almost six hours a day with their children. However, 40% of Japanese fathers regret this situation. Being fathers has become fashionable in Japan. Unlike previous generations, young Japanese willingly “walk” their babies. Several magazines for young fathers have emerged in Tokyo (Shimoda, 2008). Fathers who are younger, more educated and, most importantly, involved in real communication with their children are less likely to physically punish their children.

Gradually, this is changing public consciousness both at the political and at the everyday, community level. Interesting in this regard is the experience of the city of Kawasaki, located in Tanagawa Prefecture between Tokyo and Yokohama (https://www.endcorporalpunishment.org/children/countries/japan/japan-research-2.html).

Kawasaki is the ninth most industrialized city in Japan by population (about 1.4 million people). In 2000, his municipality voluntarily adopted the “Kawasaki City Child Rights Rule.” This rule completely prohibited corporal punishment of children anywhere. Deciding, of course, is easier than implementing. In March 2002, city officials conducted a professional survey of 4,500 local children ages 11 to 17, of whom 2,061 responded to two questions about corporal punishment, among others. When asked about their personal experience of corporal punishment in the family, 9.7% of children said that they were subjected to it often, and 27.9% - sometimes. When asked what they thought about corporal punishment, 25.2% of children said they were strongly against it, 7.5% thought it was reasonable, and 43.9% thought it was an acceptable way to discipline children. Among 600 city officials surveyed, 42.3% spoke out against corporal punishment of children in the family. This is a lot for officials.

The city council was not satisfied with this. In 2008, local authorities carried out new research to find out how self-esteem in children and adults relates to their developmental environments, including corporal punishment. It turned out that adults with a high degree of self-esteem corporally punish their children almost half as often as those who have little self-esteem. In particular, politicians and officials with low levels of self-esteem physically punish their children much more often than those with high levels of self-esteem. Corporal punishment also has negative effects on children. Children with a high degree of self-esteem feel that adults treat them attentively, listen to them, etc. But children with low self-esteem were significantly more likely to experience corporal punishment from their parents and guardians. Overall, the study found that when adults hurt them, children accepted it obediently and patiently. But this reaction is most typical for children with low self-esteem. These children rarely express their true thoughts and feelings to adults. In other words, corporal punishment inhibits the formation of citizenship and social activity. Maybe this information will help further soften morals?

It remains to wish the Kawasaki City Council success in its difficult work. It seems that the city authorities there do not use children for their own PR, but really love them.

Let's summarize.

1. Corporal punishment is the oldest and most universal form of disciplining children, but their meaning, functions and historical dynamics can only be assessed in a broad sociocultural context.

2. Just as the image of a child is flesh of the image of a person accepted in society, so the degree of prevalence and intensity of corporal punishment of children is flesh of the forms of punishment accepted in society and disciplined by adults.

3. The evolution of attitudes towards corporal punishment and corresponding pedagogical practices are meaningfully and statistically related to a number of socio-economic and cultural factors (social complexity, culture of violence, the number of socializers, inequality of opportunity and power, etc.), the relationship of which is problematic.

4. One of the main factors determining the prevalence of corporal punishment of children is religious attitudes and values, and different religions differ in this regard.

Chapter 2 A BIT OF HISTORY

Civilizations were founded and maintained by theories that refused to be governed by facts.

Joe Orton

From religious discourse to pedagogical

If we move from cross-cultural, ethnographic and religious studies to conventional narrative history, corporal punishment of children appears to be universal, but far from uniform. There are especially many variations in the meanings attributed to them and in the methods of their legitimation. The greater the value and autonomy ascribed to the child and the more complex the process of his socialization becomes, the more religious discourse is complemented and then replaced by pedagogical discourse, the focus of which is an implied concern for the welfare of the child. However, empirical data on this matter are fragmentary and look more illustrative than conclusive.

Already in ancient Greece, the styles of raising children, and even more so the methods of disciplining them, were not uniform.

In Sparta, where the upbringing of children was collective and aimed primarily at training warriors, discipline was harsh and uniform, and it was monitored not only by adult educators, paidonoms, but also by their assistants from among older teenagers - irenes, or eirens. When initiated into the Eirens, 14-year-old boys were subjected to various painful tests, including public flogging, which they had to endure without moaning or crying. After this, they became assistants to the paydonoms in the physical and military drill of other teenagers and received the right to physically punish them.

In Athens, the system of socialization of children was more differentiated and individualized. Boys here were raised separately from girls, and collective education was supplemented by home education. Neither one nor the other could do without corporal punishment.

According to Plato, “a child is much more difficult to pick up than any other living creature. After all, the less a child’s mind is directed in the proper direction, the more playful, frisky he becomes, and, in addition, surpasses all other creatures in impudence. Therefore, it is necessary to curb it by all possible means...” (Plato. Laws, 808 d).

Which ones exactly?

“It’s good if the child obeys voluntarily; if not, then he, like a crooked bent tree, is straightened with threats and beatings” (Plato. Protagoras, 325 d).

Aristotle also writes that children are naturally disobedient, which must be overcome by force (Politics, VII, 17)

Ancient Greek thought associates the most severe corporal punishment not with parents, but with teachers. In classical Greece, a "teacher" was a trusted slave, often of foreign origin, to whom a father entrusted the care of his children. Since the parents entrusted the teacher with the most unpleasant, “dirty” part of educational work, the child’s hostility was directed primarily at him. Ancient authors often write about teachers ironically, as good-for-nothing, gloomy grumblers and faultfinders. Later, even the expression “sour and pedagogical face” appears (see: Bezrogov, 2008). If progressive authors of the New Age compared a school based on coercion with a barracks, then Xenophon, on the contrary, compares the cruel commander Clearchus with a teacher:

“There was nothing attractive about him, he was always angry and stern, and the soldiers felt before him like children before a teacher” (Xenophon. Anabasis, 2:12-13).

It is important to keep in mind that the teacher did not so much teach the child (this was done by specially trained professional and expensive teacher-mentors), but rather disciplined him. Ancient authors do not describe the technique and tools of flogging in detail (perhaps out of respect for freeborn children).

Although corporal punishment was generally considered normal, some ancient Greek philosophers questioned its effectiveness, especially when applied to education. According to Pythagoras (6th century BC), “correctly carried out teaching ... must occur at the mutual desire of the teacher and student,” “all study of the sciences and arts, if it is voluntary, then correctly achieves its goal, and if involuntary, then useless and ineffective."

Subsequently, this becomes the fundamental position of the ancient Greek theory of education - paideia.

Unlike the slave-teacher, the mentor-philosopher is always described with respect. Status and age differences do not exclude some equality. This is a relationship between free people conducting a dialogue in which forceful arguments do not work.

“All ancient texts condemned those who tried to return (or maintain) the restrictive control of the teacher over the mature pupil - no matter how useful and protective this control was” (Bezrogov, 2008).

The concept of Teacher with a capital T, to which Christianity later appeals, is formed precisely here.

If the quality of the teacher could be discussed, then parental, especially paternal, authority, whatever it was, was not subject to doubt or criticism. Aristophanes in the comedy “Clouds” describes the “modern” son of Pheidippides, who, after studying with Socrates, dared to object to his father Strepsiades and even raised his hand against him, as a result of which the following dialogue arose:

Strepsiades

But it is not customary anywhere for a parent to be flogged.

Pheidippides

And who introduced this custom - he was not a man, like you and me? Didn't convince our grandfathers with the speeches? So why can’t I introduce a new custom, so that children can return beatings to their parents? And the spanking that we received before the new law will be brushed aside and forgiven for being too old. Take the example of roosters and creatures similar to them. After all, they beat their parents, but how are they different from us? One, perhaps, is that they don’t write slander.

It is obvious that the comedian does not so much problematize the relationship between fathers and sons as parody “modern” morals that are unsympathetic to him.

Disputes about the appropriateness of corporal punishment of children also took place in ancient Rome. Corporal punishment, no matter how cruel, was an integral component of the father's right of life and death over all children and household members, which no one challenged. A teacher is a completely different matter. The philosopher Libanius (314 - about 393 AD) said that oars hit the surface of the sea easier than a teacher's whip on a child's back. According to the Roman historian Suetonius (c. 70 - c. 140), a barbarian, a former equerry, was deliberately assigned as a teacher to the future emperor Claudius, so that he would severely punish him for any reason. “Your anger hardly leaves the stick,” complained the poet Martial.

However, beating a child means likening him to a slave; the educational effect of this is very problematic. In the late Roman Empire, the contradiction between corporal punishment and freedom was already philosophically understood. According to the philosopher Seneca, corporal punishment is a legal, but the most extreme means of education. For Plutarch, a child is not a vessel to be filled, but a torch to be lit. In his treatise on raising children, Plutarch wrote that rewards and explanations have a much better effect on a child than hitting or cruel treatment. More like slaves than freeborns, corporal punishment makes children timid and indecisive. As a positive example, Plutarch refers to Cato, who said that a man should not lay hands on what is most dear to him - his wife and children. When his son grew up, Cato himself began to teach him to read. He had an educated slave who successfully taught other children, but Cato did not want his son to listen to lectures from the slave, and if the boy did not learn a lesson, the slave would pull his ears.

The famous orator Quintilian (c. 35 - c. 96) also speaks out against corporal punishment. Quintilian agrees that children are “naturally inclined to the worst,” and education helps to overcome their bad inclinations. But education should mold a free person. A child is a “precious vessel” that must be treated with care and respect. When educating, one should not resort to physical punishment, because beating suppresses modesty and develops slavish qualities.

In the early Middle Ages, these guidelines were forgotten and lost for a long time, especially in school. The teacher was unthinkable without a rod. St. Augustine recalls that in his elementary school not a single day went by without beatings. His first childhood prayer was for salvation from this “killing school,” but God did not heed this prayer. Augustine compares the school to the trials of Christian martyrs. This sad experience was forever preserved in his memory: “Who would not choose death, being asked whether he wants to stop the flow of life or relive childhood again?” (Augustine. On the City of God, XXI, 14).

But this does not prevent Augustine, like other church fathers, from seeing in children’s misdeeds not a manifestation of innocence, but a sign of original sin subject to forceful treatment.

Severe punishments were considered natural and godly. Charlemagne in one of his capitularies demanded that careless students be deprived of food. Cane discipline reigned in church schools; students were beaten on the cheeks, lips, nose, ears, back and naked body. The emblem of the Grammar in Chartres Cathedral depicts a teacher threatening two children with a whip. At Oxford University, the awarding of the title of Master of Grammar was accompanied by the ritual presentation of the rod and the ceremonial flogging of the whipping boy. The famous French theologian Jean Gerson (1363–1429) wrote that “the teacher must force his students with rods”; “let them know that for every sin they will be beaten with rods,” but “no sticks or other whipping instruments that can seriously injure” (quoted in Aries, 1999).

Social norms

Schoolgirl sues government for forcing her to dye her hair

“Bullying is common in many countries because not all children are civilized at an early age, but I feel that here in Japan it is different,” said Mieko Nakabayashi. “ In the schools here, the target will be the student who is different from the others.” The same thing happens in Japanese society. The correspondence is very significant.

“So, if you're talented in class, or if you're too pretty a girl, or if you're good at playing a musical instrument, or if you just act differently, you're a target.”

Schools in Japan have a ridiculous reason for banning freezing girls from wearing tights.

This attitude is so common in Japanese society that there is a saying that sums up how anyone who stands out from the crowd is treated: “The nail that sticks up gets hammered down.”

American teacher fired from Japanese school after exposing genitals

According to Nakabayashi, there are unique social norms and a special mentality.

" The relationship that children have with their parents means that they often cannot tell them what they are going through, because in Japan one is not supposed to burden someone else with one's own problems ," she said. “It’s just as difficult to go to the teacher, as it may attract even more unwanted attention.”

Hairstyle

You also can’t do any hairstyle for school in Japan, just like in the USSR. It is important that it be strict and classic. No loose hair or curls. Dyed hair is also strictly prohibited. It is worth noting that this applies not only to schoolgirls. For example, if an adult woman has red curls, she is unlikely to be hired by a decent company.

For this reason, Japanese girls do not radically change their image. If they dye their strands, they use a dye that differs from their natural shade by a maximum of 2 tones.

Violence

Eric Fiore, owner of a private French school in Yokohama and father of three sons who went through the Japanese public education system , said there is a lot of pressure in Japanese schools for children to "conform."

Japanese school uniform

“As far as I know, my sons have never had a problem with being bullied, but I have heard some stories that would make me very angry if it involved my children,” he said. “ Children all over the world can be unkind or rude, but here it seems more extreme.”

"Boys are prone to physical violence and there will be pushing or shoving that can end in a fight, but with girls it's different," he said. “Bullying there seems to be more about excluding a girl from a group or gossiping about her, and this kind of mental abuse can be just as damaging as physical harm.”

Teachers often do not have the training or time to spend curbing bullies and victims of bullying. A Mainichi Shimbun poll found that 70 percent of teachers would like to do more to prevent bullying but simply don't have the time due to reduced staffing in schools. Being responsible for a large number of activities, lessons, quizzes and paperwork, class preparation and other work.

Teachers are afraid of losing control of the class. Salary and promotion mechanisms take this skill into account, making teachers hesitant to report bullying. Although they cannot cynically ignore the problem, we think it encourages teachers to build a defense of behavior: “everything is fine, the children are joking and having fun . When teachers do not know how to manage a class and have little authority, this is an easier default position than interfering in the life of a class where respect for them is already minimal. So they agree with the “jokers”.

Why are young children in Japan so independent?

The Education Ministry has tried to put a positive spin on the latest data, saying the 28 percent increase in reported cases shows teachers are becoming more vigilant and stricter about the previously hidden problem.

This is the first time a nationwide review of school rules has been carried out.

Objectively speaking, such treatment of children is abnormal, but such ridiculous and illogical rules exist far from only in that prefectural school. The incident sparked a movement by anti-bullying organizations to end abusive policies. They have begun a special review of the state of affairs with school rules and are looking for ways to achieve the abolition of such rules.

In February 2021, they surveyed 2,000 people aged 15 to 50 years. The questionnaire included questions about what school rules respondents had to face in middle and high school. As expected, the generation that faced the most stringent requirements was those who attended middle and high schools from the mid-1970s through the 1980s, as society struggled with school violence and other school violence. Then came a period of relaxation of the rules, but it turned out that in recent years the number of rules regarding the length of skirts, hair color, etc. has again increased. To these were added rules determining the color of underwear, a ban on plucking eyebrows, the use of hair styling products, etc. etc. There are also prohibitions on the use of sunscreen, protective lip cream, and other health and body care products. It was often said that male teachers checked the length of skirts and the color of underwear - such “educational measures” clearly border on sexual harassment.

Sunaga Yuji, Deputy Representative Director of the NGO Sutoppu Ijime! Nabi” (“Stop bullying! Navigation”) and one of the initiators of the project, told us that on the project website about 150 people spoke about their experiences of humiliating school rules. Often these were quite disgusting memories that people seemed to push out of themselves, and there were very emotional complaints about what happened 30 years ago. People expressed their irritation and anger.

Ijime

In Japan, bullying is called ijime, and it has some distinctive differences from Western bullying in that it is rooted in psychological cruelty, which may or may not involve violence. About 80% of school bullying in Japan is classified as "gang" violence, meaning entire classes against one victim, and 90% of cases are considered prolonged, lasting more than a week.

More examples:

One boy was teased for months, then beaten, then forced to steal goods for the bullies, and finally forced to eat dead bees. The child committed suicide at the age of 13. Half the class participated in the bullying, while the rest watched with mixed reactions. Teachers at the school were aware of the problem but responded only with a verbal warning to the bullies.

One boy came into class to find his desk had been turned into a memorial, with a wreath and his photograph in the center, burning incense and a condolence card filled with mocking wishes from classmates and some teachers, including his 57-year-old class teacher, who knew that the student did not die. The Japanese teacher said that if she interferes, the bullied student will "get angry" because the teacher recognizes that he is different.

https://masakaru.ru/sumashedshie-privychki-i-obychai-v-yaponii/44-dnya-ada-1988-yaponiya-koshmarnaya-istoriya-dzyunko-furuty-poxishhennoj-odnoklassnikami-shkolnicy.html

Views: 3,955

Share link:

- Tweet

- Share posts on Tumblr

- Telegram

- More

- by email

- Seal

Liked this:

Like

The Otsu incident as a reason for taking legislative action

It has been four years since the Bullying Prevention Advancement Act came into effect in 2013.

It was developed and adopted amid a number of bullying incidents. This is most notably the 1986 incident in which a junior high school student in Tokyo committed suicide due to various types of bullying, including the “funeral game.” After this, despite the wide public response that several cases of bullying received, it was not possible to propose effective methods of combating it. However, a 2011 bullying suicide case in Otsu prompted legislative action. In each case of bullying-related deaths where schools and education boards have come under fire, common threads emerge. As for the incident in Otsu, the lack of a proper response from organizational structures and the concealment of facts, which served as a reason for serious discontent in society in the following 2012, forced us to comprehend and take into account the criticism.

Thus, from the very fact of the adoption of the law, it can be understood that the situation with bullying has worsened to such an extent that it can no longer be considered as a matter of personal responsibility of individuals, for the solution of which it is enough to rely on the autonomous relationship between children and school, the problem requires the intervention of society. It could also be argued that the passage of the law is a manifestation of a community-wide determination to prevent bullying. However, there are concerns that if the focus is solely on preventing bullying between children by adults, children will become unable to address bullying as their own agents. Apparently, the question arises: how to ensure, under the auspices of this law, a balance between the intervention of adults and the independence of the child as a subject?

According to the law, every school has the following three responsibilities:

- Develop a school policy to prevent bullying;

- Create an effective organizational structure to prevent bullying;

- Take appropriate measures for prevention, early detection, and resolution of specific cases.

Pointing out the need to ensure impartiality and neutrality in dealing with serious cases (including investigations into the circumstances surrounding the incident), and the importance of responding appropriately to ensure that cases do not recur, even if this puts the school or board of education in an unfavorable light, can be expected for qualitative changes in the fight against bullying.