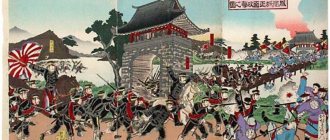

The traditional Japanese helmet is considered to be the Kabuto. It was usually shaped like a hemisphere and consisted of several metal plates or leather, and in some cases the helmets were made from a combination of these two materials. On the back of the kabuto, curved plates connected to each other with ribbons were attached, which acted as protection for the ears and neck. Like many Japanese military equipment, the helmet of the medieval Japanese samurai was intended not only for protection in battle, but also to determine the warrior’s status in society.

History of the samurai helmet

The first samurai helmet was called sakaku-tsuki kabuto, which translates as “butting ram helmet,” which was traditionally worn with tanko armor. Its distinguishing feature is a stripe, somewhat reminiscent of a crest, extending to the forehead, where it eventually takes the shape of a beak. It consisted of two strips bent into rings, between the spaces of which rectangular and sometimes triangular plates were attached. A neck protector was attached to the back of the helmet.

After a new type of armor appeared - keiko, they began to create other types of helmets with a more rounded shape - mabizashi-tsuki kabuto (translated as “helmet with a visor”), which were in use from the 5th to the 10th centuries. The shape of the mabizashi-tsuki was copied from Chinese and Korean helmets. It did not have a comb-like stripe, but instead featured a horizontal visor. At the top of the head there was a tube, which most likely served as a decoration and was attached to a round plate.

Warriors from a noble family usually decorated their helmet with gilded metal horns. This tradition appeared at the end of the 12th century, and over time the size of such horns began to increase. However, their functions included not only decorating the helmet, but also intimidating enemies, and in between they often depicted the coats of arms of clans or even the faces of demons.

The art of making military hats

These helmets were the result of craftsmanship reserved for the highest ranking samurai, as well as a visual symbol of whatever clan they represented (hence the various symbols and animals).

Mannequins were developed for 2.5 million rubles. for training medical personnel

Nastasya Samburskaya spoke about the trial with producer Viktor Drobysh

In 2020, the demand for used cars in Russia broke all records

Even women, known as samurai (aka onna-bugeisha), could fight alongside male samurai in combat while wearing kabuto helmets.

As William E. Deal explains in A Guide to Life in Medieval and Early Modern Japan, "helmets from the Warring States period came to reflect the grandeur of the era in their size, shape, and intricate designs."

Types of kabuto

There are a large number of varieties of Japanese helmets, partially differing from each other:

- Hoshi-kabuto

- Kawari-kabuto

- Zunari-kabuto

- Saika-kabuto

- Namban-kabuto

The Hoshi-kabuto was created during the Momoyama period and is believed to be the earliest samurai helmet. It was worn complete with o-yoroi armor and consisted of 12 segments, which were fastened with protruding decorative rivets.

Kawari-kabuto . The most outstanding type of Japanese helmet, due to its complexity and uniqueness, is considered the kawari-kabuto, which is translated as a “figured” helmet. Almost all kawari-kabuto were made to order in one copy due to which they were considered exclusive and extremely rare samples. Only high-ranking officials could afford such a helmet, most often they were military command ranks. But ordinary soldiers could also wear subtypes of kawari-kabuto: monari-kabuto - “peach helmet” and shinari-kabuto - “acorn helmet”.

Zunri-kabuto, translated as “helmet that follows the shape of the head,” was very common during the Edo period. It consisted of a plate running from front to back, which was attached to the rim. In the spaces between the fastenings there were two more plates. It will gain its popularity due to its cheap price and simple design.

Saika-kabuto was named after the city in which it was invented. A distinctive feature of this helmet was its eight-part crown, reminiscent of a cone. Below there was a wide crown to which the plates were attached. Most often, the saika-kabuto was made without a visor.

The Namban-kabuto was made based on the prototype of European helmets, which is why it received the name “helmet of the southern barbarians.” It looked like a Spanish cabasset, but decorated and modified in an Asian way by Japanese craftsmen.

"Modern armor" XVI-XIX centuries.

In the 16th century Japan began to establish ties with Europe, and new trends gradually emerged. By the middle of the century, firearms had appeared in the country, and it was necessary to improve armor. The ancestor of modern armor was the tosei-gusoku, the chest and back of which consisted of solid strips of metal with a leather lining. Later, okegawa-do armor arose, where the plates were connected not by lacing, but by metal rivets. The armor was made with vertical (tatehagiokegawa-do) and horizontal (yokohagi-okegawa-do) plates.

The Namban-do and Hatamune-do armor were created similar to European ones - they consisted of a solid shell and a traditional kusazuri skirt.

A cheaper variety was tatami-do and kawara-tatami-do, made of fabric or a base on which either steel or leather was sewn.

Text of the book “Samurai. The first complete encyclopedia"

Chapter 5 O-yoroi armor - a classic of Japanese samurai

Your name lives on the lips like a composer of songs! About military glory Only the feather grass rustles in the autumn field...

Saigyō (Sato Norikiyo, 1118–1190)[5]5

Translation by A. Belykh.

[Close]

Not long ago, Japanese archaeologists discovered, near the Haruna volcano in Gunma Prefecture, the remains of a 6th-century warrior dressed in plate armor, rare for that time.

The find was discovered during the construction of a local road in an area affected by a volcanic eruption. According to archaeologists, at the moment when the warrior was covered with a cloud of hot ash, he was sitting on his knees and looking towards the volcano, so his armor and the skeleton itself were well preserved. The most interesting thing, however, is that they were made of metal plates overlapping each other and in design they belonged to the rare and expensive type of kozane-yoroi. Moreover, the kind of armor that this warrior wore during his lifetime was discovered for the first time. Previously, they were found only in burial places of the nobility as ritual objects. From this, archaeologists conclude that the warrior could have been a high-ranking military man or even a local ruler. However, the most important thing is that now we can conclusively say that already at that time in Japan there were the first armor made of metal plates sane (the general name for plates made of leather or metal in kozane-do armor, usually varnished), although earlier it was believed that they appeared much later!

O-yoroi armor allegedly belonging to the legendary samurai Minamoto no Yoshitsune (1159–1189). Okayama Museum.

O-yoroi with the signs of the Masamune family. Glenbow Museum. Calgary. Canada

As noted in the previous chapter, samurai were mounted archers, that is, in the language of modern times, they were “quick reaction units” that were highly mobile. The main method of warfare for them was archery from horseback. Therefore, old armor, not quite suitable for this, already at the end of the 8th century began to be gradually replaced by new ones - o-yoroi (“great armor”), maximally adapted specifically for such a battle, although they became truly widespread only in the Heian era. Externally, the new armor was a little angular and most of all resembled a box in its shape. Their production was even more labor-intensive than the production of tanko and keiko armor, but they perfectly met their main purpose - to serve as protection for a warrior who shot from a bow while sitting on a horse. They were made from metal plates connected by leather cords into strips about 30 cm long. The resulting sets of strips were then tied together with vertical kebiki-odosi lacing, and these cords (odosi) were colored and could create a beautiful pattern on the surface of the armor. Their important feature, despite the flexibility of the connection, was great rigidity. That is, although they were made from plates, such armor did not possess flexibility at all! In addition, the box-shaped shape of the armor made it not very comfortable to wear. The person wearing them, to some extent, became... a kind of extension of the saddle. It was convenient for him to sit in them and shoot from a bow, both forward and backward, but nothing more!

Close-up of o-sode shoulder pad.

The plates for the armor of Japanese warriors could be made of either leather or metal, however, in both cases they were certainly coated with varnish to protect them from high humidity; in a damp climate, metal plates without such a protective coating would quickly rust and become unusable. It was also customary to cover them on the outside with thick, smoked nameshigawa leather. Moreover, the size of the plates decreased over time. By the middle of the Heian period (c. 10th century), standard plate sizes were 7.5 x 3.0 cm; and by the middle of the Kamakura period (c. XIII century) - already 7.0 × 2.4 cm. In order to connect the plates to each other, holes were made on them in two or three rows, through which cords were then threaded - only in this way and this process was carried out in no other way. The benefit of this design was, first of all, that the armor could easily be adjusted to fit your figure: you added a couple of extra plates or, on the contrary, reduced them - so they fit you like a glove. In some cases, metal and leather plates were alternated, sometimes larger plates were made of metal to cover particularly vulnerable areas, and leather plates were used on the sides and back. In all cases, the plates were always overlapped, so that the armor was multi-layered and provided better protection. If the plates overlapped each other in three layers, then such a connection was called tatena-shi - “no shield needed” - such armor provided such strong protection to the warrior wearing it.

And here you can clearly see the cords that fastened the o-sode.

If you look at the o-yoroi before it is put on, you can see that it consists of only two parts, with the front, left and back parts being connected together into one whole. The first to be worn was a separate right part - wakidate, which was supposed to be held on a cord thrown over the left shoulder, which was tied under the armpit, while another cord held it on the belt. Then the rest of the armor was put on, which was supposed to cover the chest, left side and back and which was laced on the right over the wakidate, after which a belt was tied to hold the armor on the hips. Large and heavy o-sode shoulder pads, consisting of 6–7 rows of plates, played the role of a kind of flexible shields and were attached to the shoulder straps using cords or straps. The support point for them on the back was a large and heavy agemaki bow made of thick silk cord, connected to the shoulder pads with special cords. Regardless of the colors of the armor lacing, these cords, like this bow itself, were always red.

Agemaki knot on the back of the helmet.

The cuirass of the o-yoroi armor - that is, the actual chest and dorsal part of the shell, called do (or ko - since both words can be translated as shell if desired!), usually consisted of four rows of plates called nakagawa. Moreover, these plates were the same both on the chest and on the back. The shoulder straps that held the armor on the shoulders were fastened to the chest plate of the muna-ita with takahimo clasps. They were double silk cords, one pair of which had a loop at the end, and the other a wooden or bone oval button. Easily vulnerable fastener attachment points were covered with two plates. The right one was larger and was called sentan no ita. To make it movable and not interfere with the movements of the right hand, it was assembled from three short rows of small sane plates, and a small iron plate covered with leather was fixed at the top. For the left hand, mobility was less important, so the left plate was narrow, elongated in height, made entirely of metal and fixed to the armor motionlessly. It was called kyubi-no-ita. The plates were often covered with leather or fabric and decorated with gilded copper plates of various shapes.

Bow and lacquered arrow quiver. Exhibition “Samurai. 47 Ronin". Moscow.

Kusazuri legguards consisted of five horizontal rows of plates. Three kusazuri were attached to the cuirass - one each at the back, in front and on the left side. The fourth of them was a continuation of the wakidate plate.

The plates from which the cuirass was made were usually not visible on the chest, since they were covered by a large piece of tanned leather - tsurubashiri-do gawa. This was done so that when fired from a bow, the bowstring (tsuru) could slide freely over the skin without the risk of catching on the plates. The design used was red and blue circles on a fawn background with stylized images of Chinese heraldic Xixia lions in blue colors inscribed in them, and the circles themselves were inscribed in a lattice of red or red-blue diamonds. The sides of the rhombuses were formed by a stylized floral ornament, that is, the pattern decorating the skin was quite whimsical and labor-intensive. Sometimes the leather was dyed even before smoking; then the paints changed their color under the influence of temperature, which resulted in pieces of leather with a brown pattern on a yellow background of various shades. The geometric patterns described above were most characteristic of the Heian era. During the Kamakura (1185–1333) and Nambokucho (1336–1392) eras, other motifs began to appear in them, for example, images of dragons or Buddhist saints. They stopped adhering to strict geometry, which is why the same lions and plants were now located in seeming disorder.

Karabitsu eroi - a chest for storing armor.

It is obvious that tanned leather was widely used in Japanese armor, from finishing the same plates and making cords for them to the design of the breastplate and other parts of the armor. Usually they used deer suede or buffalo leather for this purpose. It is interesting that from the 7th–8th centuries, when the Japanese adopted Buddhism from the Chinese, the killing of animals, especially useful to humans, began to be considered a great sin. Therefore, all activities associated with contact with the corpses of people and animals (funerals, skinning carcasses, processing skins and dressing leather parts of armor) were now carried out by a caste of pariahs called burakumin or eta and considered “subhumans.” However, both samurai and Buddhist monks did not refuse leather armor, as well as killing their own kind.

In the Heian era, especially at the very beginning, the connecting cords with which the armor plates were connected to each other were made mainly of leather, sometimes dyed or covered with ornaments embossed on it. Later, they began to be made from pre-dyed silk yarn, and the lacing process itself turned into a real art, in which aesthetic and practical aspects were closely intertwined: by the color of the cords and their patterns on the armor, samurai now easily distinguished their own from strangers. It is believed that the custom of distinguishing clans by color came into fashion during the reign of Emperor Seiwa (856–876), when the Fujiwara family chose light green as their color, Taira - purple, Minamoto - black, Tachibana - yellow, etc. Armor the legendary Empress Jingu, for example, had dark crimson lacing, which is why they were called “red embroidered armor.” On the other hand, the study of battle paintings shows that warriors on opposing sides very often wore the same colors, and although red was the most preferred, the colors of the armor of famous warriors could be very different. For example, in the “Unofficial History of Japan” (“Nihon Gaishi”), dating back to 1184, it is written: “ ... the one in red armor, girded with a large sword, was called Hatakeyama Shigetada; ‹…› the one in black armor was called Kajiwara Kagesue, and the one in yellow armor was called Sasaki Takatsuna

" Moreover, all of them had nothing to do with the above-mentioned clans. And, of course, everyone knew what the armor of these warriors looked like. In addition, it was simply necessary for the samurai to know who was wearing what: after all, in Japan of the 10th–15th centuries, whoever cut off the head of a noble enemy received a rich reward from his overlord. There was a special term, shukyu no ageru, borrowed from Ancient China and meaning “took the head and got promoted.” As for white (in Japan it was the color of mourning), it was usually worn by warriors who demonstrated their desire to die in battle or who fought for an obviously hopeless cause.

Karabitsu era (with armor inside).

The armor differed not only in the color of the cords, but also in the density of their weaving. And if the clan affiliation of a warrior was judged by color, then by the nature of the weaving - his rank and position in the clan. Tight and skillful lacing, which almost completely covered the surface of the plates, indicated his high rank and was used mainly in the armor of horsemen, while among the ashigaru (“light-footed”) infantrymen it was very rare, and the cords themselves connecting the armor plates were A little. Common colors for armor lacing were aka (red), hi (orange, "fire"), kurenai (crimson), kuro (black), midori (green), kon (blue), ki (yellow), cha (brown, " tea"), shiro (white) and murasaki (purple). The blue color, obtained from indigo dye, was more popular than others, primarily because this dye protected the silk from fading, while madder and soybean (red and purple colors) destroyed it, which is why the red-violet lacing had to be restored more often than any other. That is, the warrior who wore such red armor needed to give it to the master for repair more often than others, which was not cheap at all! The leather straps odoshige (which literally means “terrifying hair”), made of white leather with images of red cherry blossoms printed on them, also looked very elegant. A special cord (mimiito), the color of which differed from the color of the main lacing, was also braided around the edges of the armor, and it was usually thicker and stronger than all other cords. The plates were also usually painted in different colors, for which organic pigments were used. So, they were painted black with ordinary soot; in bright red - cinnabar, which was obtained by mixing sulfur and mercury; brown color was obtained by proportionally mixing red with black. The popularity of dark brown lacquered plates was caused by the widespread custom of drinking tea in Japan and the fashion for antique objects, which were traditionally preferred to new ones, while red-brown varnish made it possible to create the impression of a metal surface corroded by rust. Some craftsmen combined varnish with chopped straw and even added crushed coral to it. In particularly rich armor, “gold varnish” was used, obtained by adding gold dust or thin sheet gold to it. Red was considered the color of war. The blood on the red armor was not so noticeable up close, but from a distance, on the contrary, they made a terrifying impression: it seemed that the people wearing them were splattered with blood from head to toe. It should be noted that the armor, painted in different colors, was very beautiful and fully reflected the refined tastes of the Heian era, so it is not surprising that the samurai loved them so much that for a long time - from the 8th to the 15th centuries - they considered them the only worthy great warriors.

O-yoroi armor with white lacing. Tokyo National Museum.

Cords for armor were of two types: leather - kawa-odoshi and silk - ito-odoshi. Dense one-color kebiki-odoshi weaving was the most popular and at the same time the simplest. Weaving with leather cords, when small designs in the form of sakura flowers, usually dark blue, brown or green, were stamped on yellow, white or fawn stripes, was called kozakura-odoshi. These were the most ancient types of weaving, apparently appearing at the turn of the 10th–11th centuries and enjoying great popularity during the wars between the Minamoto and Taira clans. If, against the background of a single-color weaving, one or two upper rows of plates were woven with white cords, then this was kata-odoshi weaving. If cords of a different color were placed at the bottom, it was called koshitori-odoshi (koshi means "hips"); and if the stripes alternated, then it was already dan-odoshi. The weave of multi-colored stripes was called iro-iro-odoshi. A variant of iro-iro-odoshi weaving, in which the color of the stripe in the middle was replaced by another, was called katami-gawari-odoshi - literally “replacement for half the body.” This type of weaving was very popular during the Muromachi era. Very complex and elegant was the suso-odoshi weaving that spread from the 12th century, when the color of each new strip was darker than the previous one, starting from the top white stripe down, and very often a yellow stripe was placed between the top white color and the darker colors below. If the light stripes were at the bottom and the dark stripes at the top, then it was a type of nioi-odoshi, and both types of weaving were popular during the Gempei War. Quite rare was the ancient weaving in the form of chevrons: saga-omodaka-odoshi with an upward angle and omodaka-odoshi with a downward angle. Tsumadori-odoshi had a half-corner chevron pattern and was often used in the early Muromachi era. Checkerboard weaving was called shikime-odoshi. The zigzag pattern on fushinawa-me-odoshi leather cords was most popular during the Nambokucho period. The lacing could also depict the coat of arms of the owner of the armor - his mon. For example, the image of the Japanese swastika manju (facing left) distinguished the Tsugaru clan, which dominated northern Japan. The weaving lines could also go in waves, as, for example, in tatewake-odoshi weaving, or they could form an original color pattern, as, for example, in kata-tsumadori-odoshi weaving.

In fact, all parts of the armor had to have the same lacing pattern, whether it was an o-sode pattern or a kusazuri pattern. However, on the do-maru and haramaki-do armor, their o-sode could have one pattern, which was also repeated on the chest and back, but on the kusazuri plates there could be a different one. Most often, the darkest color of the stripes on the o-sode was used.

At that time, along with the o-yora, they wore an armored sleeve, kote, only on the left hand, so that the right remained completely free for pulling the bow string. The armored sleeve looked like an ordinary cloth bag, which was reinforced on the outside with iron plates sewn onto it and which was tied under the armpit. Under the armor, the samurai wore a yoroi hitatare - a robe decorated with embroidery and pompoms. The large, baggy hakama pants were tucked into the leggings, and the wide sleeves were fastened with cords at the wrists. For convenience, the left sleeve was not tucked into the kote, but was pulled out and tucked into the belt. Leggings were simply three bent iron plates that were tied to the leg. Bearskin shoes and leather gloves for archery completed the samurai's armament from the neck down.

A mounted samurai in o-yoroi armor and accompanying foot soldiers in haramaki-do armor. Tokyo National Museum.

With o-yoroi armor, it was customary to wear a heavy kabuto helmet, which consisted of several iron plates fastened with large conical rivets, the heads of which protruded above their surface. Sometimes, looking at these rivets, you might think that they are too large, but most often we see not the rivets themselves, but the hemispheres covering them from above for the sake of beauty!

In the crown of the helmet, a hole with a diameter of about 4 cm was made at the top - tehen, which served not only for ventilation, but also for more firmly securing the helmet to the head. This was done as follows. The hair was gathered into a knot. Then the samurai eboshi cap was put on the head, and this knot, together with part of the cap, was straightened out through the hole on the top of the helmet. And this was very important, since helmets at that time had no lining and were held on the head only thanks to the ties under the chin and this tuft of hair. During the Kamakura period (XIII-XIV centuries), samurai stopped collecting their hair in a knot, so the hole in the helmet lost some of its functions. Moreover, arrows could get into the rather large hole on the top of the helmet when the samurai tilted their head forward[6] 6

It’s interesting how the Heike Monogatari (“The Tale of the House of Taira”) talks about the possibility of arrows falling into the hole of the tehen: “Hold hands and cross in a chain. If the horse's head disappears under water, raise it; If the enemy shoots an arrow, don't grab your bow to fire back. Tilt your head and the arrow will slide across the back of your helmet, but don't bend too low or the arrow will hit the hole on the top of your head."

[Close]. Eventually they stopped making this hole; and by the beginning of the Muromachi period (XV century), their existence was only reminded of by the decorations that were attached in its place from the outside. The large, curved butt plate of the helmet, like that of a Roman legionnaire, - shikoro, like all other parts of the armor, was assembled from kozane plates. But note that its edges were curved outward and upward in the shape of the Latin letter “U”. These protrusions - fukigayoshi - were covered with embossed leather, just like the visor of a helmet, and protected the side of the warrior’s face. The helmet was decorated with another small agemaki knot, which was located at the back, and various small decorative copper details.

Hoshi-kabuto helmet with paulownia flower emblem between kuwagata.

The total weight of the armor reached 27–28 kg; at the same time, the load on the shoulders was somewhat reduced by the saddle, on which the cuirass rested with its lower edge. However, when the samurai dismounted, the full armor proved too heavy for prolonged combat. In addition, they were quite long, so that there was even an idiom “wearing long armor.” In any case, it must be emphasized that the o-yoroi armor, like all other armor of warriors of that time, was not a uniform for them. Each set was made to order and made strictly individually, just like knightly armor in Western Europe, although in appearance they resembled each other, like twins. Nevertheless, among them there were not two identical, and each such armor had its own name, emphasizing the characteristic features of its design. The name of the armor necessarily included the color of the cords, the name of the material from which it was made, the type of weaving and, finally, the type to which this armor itself belonged. For example, the o-yoroi armor with alternating red and blue silk cords had the following name: aka-kon ito dan-odoshi yoroi, and the color that was on top always came first. And the name aka-kozakura-shiro-gawa-odoshi-no-o-yo-roi belonged to the o-yoroi armor, in which the lacing was made with leather odoshige belts with red cherry blossoms depicted on a white background!

A helmet with such a huge shikoro could be either very ancient or a remake, custom-made. Exhibit at the Chasen Museum of Art at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Wisconsin.

Sword from the beginning of the Kamakura period. This sword was held with one hand, but it already has all the signs of a classic nihonto - a Japanese sword with a curved blade. Tokyo National Museum.

As for the offensive weapons used by warriors wearing o-yoroi armor, they usually carried a sword, a dagger, a bow and a halberd with a long sword-like blade called a naginata. The sword was not yet considered the main weapon of a samurai at that time, but by the 11th century both its design and method of use had reached its perfection. But still, it was just a weapon, the same as any other, and the legends about the samurai sword, like about the samurai themselves, had yet to take shape. The swords of early warriors, known as tachi, were worn on the belt with the blade facing down. This was, judging by the images on the scrolls, the only generally accepted method, since this was the only way it could be worn with the bulky o-yoroi armor. A wooden or wicker disk was attached to the scabbard, onto which a spare bowstring was wound, since the bow was the warrior’s main weapon at that time, and he should have taken care of even such “little things” so as not to remain unarmed in the midst of battle! The bows were compound, like most Asian bows. They were assembled from bamboo strips, individual parts were made from other types of wood, and the whole thing was wrapped in rattan fiber. One of the curious features of the Japanese bow was that when shooting it was not held in the middle, but approximately in the place that was a third of the length from its lower end. This made it more convenient to shoot from the saddle. Samurai spent hours practicing the art of shooting, shooting long bamboo arrows from galloping horses. Arrowheads had different shapes and, accordingly, served different purposes. The open, V-shaped, scissor-like points may have been intended for cutting cords holding armor together, although they were most likely originally used for hunting. A funny tip in the form of a large wooden turnip with through holes, which whistled in flight, was also in the warrior’s quiver, and such arrows were used to give signals and intimidate the enemy. At the same time, the samurai carried arrows in a quiver, which was usually hung on the belt on the right, and they pulled them out of it not over the shoulder, as was customary in the West, but down!

The armor and weapons described here clearly indicate that the peaceful bureaucracy, which had been in power since the Great Reforms, gradually began to succumb more and more to pressure from the new military clans, and they more and more felt themselves to be a kind of single community, a military brotherhood. Wars with the aborigines on behalf of the government gave samurai in the border areas good practice, but they learned real military science in battles with exactly the same warriors of the opposite side. However, the influence of individual mutinies and uprisings on the general course of Japanese history would be insignificant if it did not contribute to the formation of samurai traditions. In subsequent years, samurai were inspired by the call to imitate the deeds of their ancestors, so much so that when challenged to a duel it became the custom to proclaim their ancestry and the history of their house, which gave them greater significance both in their own eyes and in the eyes of their opponents.

This woodcut by Kobayashi Kiochika (1847–1915) depicts the samurai Tairano-Tadanori about to fall asleep under a cherry blossom tree. It is interesting, however, not for its plot, but for how precisely all the details of his o-yoroi armor are written on it. Notice that he is sitting without removing the waidate plate that covers his right side. All its ties and the method of fastening are clearly visible. Los Angeles Museum of Art.

Kabuto[ | ]

Hoshi-kabuto Konishi Yukinaga in a helmet with maedate and wakidate.

Engraving by Utagawa Yoshiiku, 1867 Portrait of Yamanaka Yukimori (English) Russian. (1545-1578) wearing a helmet with maedate. Woodcut by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, 1886. Early helmet - hoshi-kabuto

(Japanese 星兜), worn with o-yoroi armor, had a hemispherical crown consisting of 8-12 segments, riveted between 5-6 decorative rivets.

On the top of the helmet there was a tehen

.

koshimaki

plate was riveted around the base of the crown .

It was formed under the influence of the shokaku-tsuki-kabuto

and

mabizashi-tsuki-kabuto

.

iti-mai-fuse-kabuto

which are not widely used , the crowns of which may have been made of a single piece of iron. A small, almost vertical visor was riveted to the front. There were 2 or 4 holes made in the crown, covered with rivets, into which leather straps were attached, and a silk chin cord was attached to them. A shikoro consisting of 5 vertical rows, each of which consisted of 100-138 small plates, was attached to the koshimaki.

Since the end of the 12th century[2], kabutos have been decorated with the helmet figure of a kuwagata

, usually in the form of flat “horns” made of gold or copper, and served to distinguish famous warriors[3].

At the same time, dayenzan-bachi

or

maru-bachi

. Their main feature was the almost completely hemispherical shape of the crown, hence the name. It consisted of 12-28 plates. Small ribs were made along the rear edge of each plate, significantly increasing the strength of the helmet. In addition, they were also decorated with silver or gilded copper plates. Since the 13th century, a cap sewn to the crown of a helmet has been used as a balaclava. By the 14th century, the crown of the Hoshi-kabuto already required up to 36, and up to 15 rivets for each connection.

In the 15th century, the size of the helmets increased, and the degree of decoration decreased. As a result, a new type appeared - suji-kabuto

(Japanese: 筋兜), the rivets on the crown of which were not visible.

However, ribs were visible on the edges of the plates. The visor was no longer vertical, but was at a certain angle. As a result of expansion, the sikoro

, so another protection was additionally attached under it, which was rectangular plates sewn onto a fabric base.

At the same time, masques became widespread - co-men

, or

mempo

, often had grotesque features: a bared mouth with teeth, a hooked or flattened nose, a mustache or beard.

Such masks were made of iron and varnished; tare

[4].

In the 16th century, with the growth in the number of feudal armies, kabuto were divided into 2 types. The first, used by common soldiers, consisted of 6, 8, 12 or 16 segments; on officer helmets their number was 32, 64, 72 or 120, and such multi-segmented helmets, due to unreliability, were most likely non-combat. In addition, the hemispherical shape of the crown is losing its monopoly and is largely being replaced by other forms - mainly asymmetrical, with protruding sides.

Helmet figures become more complex and, as a rule, consist of wakidate

(side horns) and

maedate

(central figure depicting the sun or month)[5].

Along with metal ones, wooden bull horns[6] were also widely used, as well as deer antlers made of wood covered with varnished paper - rokkaku

[7]. At the same time, many non-standard helmets appeared - kawari-kabuto, including figured ones that imitated the heads of animals, mythical creatures, plants, sea waves, etc.[8].

Samurai image

The armor and weapons of the samurai created a rather impressive appearance, and now in many films Japanese warriors are shown just like that. In reality, everything was not like that. Their height in medieval Japan was approximately 160-165 centimeters, and their physique was thin. In addition, there are many references that it is likely that samurai descended from an ethnic group of the small Ainu people. They were much taller and stronger than the Japanese, their skin was white, and their appearance was largely the same as the Europeans.

Female samurai

Women Samurai

When we say the word “samurai”, the image of a man immediately comes to mind, however, in ancient Japanese chronicles there are many references to women samurai, who were called onna-bugeisha. Women and samurai girls took part in bloody battles along with the stronger sex. The naginata (samurai long sword) was the weapon they used most often. An ancient Japanese bladed weapon with a long handle (about 2 meters) had a curved blade with a one-sided sharpening (about 30 centimeters long), almost an analogue of a melee bladed weapon - a glaive.

There are practically no mentions of female samurai in historical chronicles, which is why historians assumed that there were very few of them, but the latest research into historical chronicles has shown that onna-bugeisha contributed to battles much more often than is commonly believed. In 1580, a battle took place in the town of Senbon Matsubaru. According to the results of excavations, out of 105 bodies discovered at the battle site, according to the results of the DNA analysis, 35 belonged to the female sex. Excavations at other sites of ancient battles have yielded approximately the same results.

Notes[ | ]

- Nosov K. S.

Armament of the samurai. - M.; St. Petersburg, 2004. - P. 23. - Samurai helmet // Amazing Japan.

- Conleyn T.D.

Weapons and equipment of samurai warriors. - M., 2010. - P. 44. - Sinitsyn A.Yu.

Samurai - knights of the Land of the Rising Sun. - St. Petersburg, 2011. - P. 292. - Weapons and armor of samurai // Miuki Mikado. Virtual Japan.

- Turnbull St.

Samurai. Weapons, training, tactics. - M., 2009. - P. 33. - Conleyn T.D.

Decree. op. — P. 122. - Nosov K. S.

Decree. op. — P. 81.

LiveInternetLiveInternet

Perhaps you know how to fold caps and caps from newspaper.

All fathers and mothers should be able to do this. Especially if there are boys in the family.

It turns out there are other options. And more interesting.

I liked this samurai helmet .

Made without scissors and glue from paper (or newspaper). Folds using the origami method.

Let's make our boys happy!

We will need:

a sheet of thick paper measuring 50x50 cm and a ruler.

1. Fold the square into a scarf. You will end up with a large isosceles triangle.

2. Bend the long side of the resulting triangle towards you. Smooth out the crease with a ruler.

3. Turn the piece over with the fold down so that the top of the triangle is facing you. Bend the acute corner of the triangle (“horn”) upward toward you. Connect the “horn” to the top of the triangle.

4. Bend the second sharp corner in the same way. Smooth the paper with your hands so that it does not wrinkle. You should end up with a square with small “horns” sticking out of one corner.

5. Grasp these “horns” and fold the top layer of paper that formed the square in half.

6. Then bend the “horns” slightly to the sides: one to the right, the other to the left. Iron the workpiece again with a ruler.

7. Fold the next layer of paper (the triangle at the bottom of the square under the “horns”) so that its vertex is located in the middle of the upper triangle “between the horns.”

8. Fold the base of the middle triangle again so that it is flush with the base of the upper triangle - you should get a border.

9. Turn the workpiece over to the reverse side, with the “horns” facing away from you. Fold the bottom edge of the square up. You will get a small triangle, like in the picture.

10. Fold small side corners under the left and right “horn”. Smooth out the folded corners with a ruler.

11. Fold the base of the small triangle (which we folded in step 9) four times, tucking the side corners inside the fold. As a result, you should end up with a triangle shape with a border at the base and small “horns” at the top.

12. Carefully iron the bottom of the hat with a ruler so that the side corners do not jump out from the fold, otherwise the hat may unfold.

The samurai helmet will look more elegant if you paint it.

- Prime the entire cap with bronze paint from a spray bottle, first covering the central triangle.

- In the center of the white triangle, draw a red circle - the symbol of Japan.

- Paint the parts under the horns with red paint, and the parts above the horns with black paint.

Well, now you can play!

Nowadays there are many opportunities to please children. How do you like, for example, such a children's motorcycle powered by a battery? It's not cheap, of course. But it's very good as a gift! There are even ones for kids 2-5 years old.

Middle_name

A series of messages “activities and toys for children”:

Part 1 - Finger painting Part 2 - Toy Cat-Loun MK (Video) ... Part 38 - Tiger cub made from pompoms MK Part 39 - Idea for a children's party: a pear with a surprise Part 40 - Samurai helmet made of paper Part 41 - Children's house made from a beach umbrella (idea from Burda) Part 42 - Motorcycle made from a lighter!)))) Wow! ... Part 47 - Finger games for babies from 6 months to 2 years Part 48 - Soft doll houses. Ideas and master classes Part 49 - Scops Owls doll Master class

Number of samurai

There is an opinion that samurai were chosen warriors and there were very few of them. In reality, samurai were armed servants close to the nobility. Subsequently, samurai became associated with the bushi class - middle and upper class warriors. A simple conclusion suggests itself - there were significantly more samurai than is commonly believed; more than 10% of the Japanese population were samurai. And since there were many of them, they had a significant influence on the history of the empire; It is believed that today every Japanese has a piece of the blood of great warriors.