Economic development and social structure of Japan in the second half of the 17th - 18th centuries.

The Tokugawa regime finally took shape under the third shogun, Tokugawa Iemitsu (1623-1651), around the middle of the 17th century. Despite being mostly reactionary. the nature of the Tokugawa order, until the end of the 17th - beginning of the 18th centuries. During the period there was a slight increase in the productive forces. This was explained by the fact that after continuous internecine wars of the 16th century, which catastrophically ruined the peasantry, Japan entered a period of long-term internal peace.

There was some improvement in agricultural technology, an expansion of acreage, and an increase in productivity, as a result of which Japan's national income increased significantly (from 11 million koku of rice at the beginning of the 17th century to 26 million koku at the end of it) and the population increased.

The development of productive forces was reflected in the success of crafts and a significant expansion of domestic trade. However, all this was accompanied by such processes as the development of commodity-money relations, the growth of differentiation of the peasantry and the strengthening of trade and usurious capital, as well as the village elite associated with it. This sharply intensified the internal contradictions of the country's feudal economy. The bulk of the peasant population, under the influence of the penetration of commodity-money relations into the villages, quickly went bankrupt. Up to one hundred varieties of rice, 12 varieties of wheat, barley and millet are planted. Cotton and tobacco are also grown.

The nobility spent huge amounts of money on entertainment. This led to the enrichment of the urban bourgeoisie and an increase in the debt of samurai and princes, who increasingly turned to merchants and moneylenders for loans. At the same time, the exploitation of the bulk of the already disadvantaged peasantry intensified, which in addition paid for the wastefulness of the nobles.

And if in the 17th and early 18th centuries. In Japan there is some growth in the productive forces, but in the subsequent period clear signs of decline are revealed. The size of the cultivated land area remained unchanged. Agricultural profitability fell due to declining yields. The peasant population was ruined under the burden of unbearable exploitation.

The cessation of growth in the peasant population became the second distinctive feature of this time. According to government censuses, in 1726 the population of Japan was estimated at 29 million people, in 1750 - 27 million, in 1804 - 26 million.

The reason for the population decline lay in the enormous mortality rate from famine and epidemics. In 1730-1740, the population decreased by 800 thousand people as a result of famine, and in the 1780s - by 1 million. In these harsh conditions, peasants widely practiced infanticide.

The end of the 80s of the 18th century. was marked by a wave of peasant uprisings and uprisings of the urban poor, which were recorded in official chronicles under the name “hunger riots,” which were threatening for the feudal regime.

The cities of Japan were divided into: cities of the shogun, cities of the emperor and free cities. At the end of the 18th century. The first manufactories begin to emerge, first in the salt-making and distilling industries. The first weaving workshops were established in Kyoto. Soon textile manufactories appeared - weaving and spinning, then dyeing and pottery. Most of these manufactories employed hired workers.

In the social hierarchy, the shogunate established the shi-no-ko-sho system, where shi is represented by the samurai, but by the peasantry, ko by artisans and sho by merchants. Merchants united in guilds. At the very bottom of the social ladder were the barakumin (“village residents”) - people engaged in “unclean” professions: actors, obstetricians, leather cutters. Their position was hereditary.

Samurai were divided into many different categories: kuge - the imperial family and its immediate relatives. All other feudal clans were called "buke" (military houses). The ruling princes (daimyo), in turn, were divided into three categories: the first belonged to the house of the shogun and was called Shinhan, the second - fudai - included princely families that had long been associated with the Tokugawa house, dependent on it militarily or economically and therefore being its main support. Tozama - consisted of sovereign princes who were independent of the Tokugawa house and considered themselves feudal families equal to it.

Influential samurai were called hatamoto, and ronin were wandering samurai. Only a samurai had the right to carry two swords - long and short. The Code of Samurai Honor - Bushido forbade samurai to engage in anything other than military affairs. The samurai had the right to death - sepuko.

The Mikado (emperor), who lived in the old capital of Kyoto, performed only religious and ceremonial functions, and actual power was completely concentrated in the hands of the shogun. The Shogun lived in the city of Edo. With him was the Tyro council (of 5 people). The shogun's headquarters, the bakufu, served as the government. The shogun had the right of hostage: all feudal princes were obliged to visit Edo every year, at the shogun's court and live there with their retinue and family. At the same time, they had to regularly present gifts to the shogun along with gold and silver coins. After a year of stay, the daimyo left, but had to leave their wife and children as hostages in Edo. Thus, any disobedience entailed reprisals against the family.

The Mikado was surrounded by the aristocratic nobility of the Kuge, who did not have land, and therefore did not have sufficient economic and political power. She received her salary in rice not from the Mikado, but from the shogun and, therefore, was completely dependent on him. Thus, the structural uniqueness of the feudal military-administrative and ideological mechanism of Japan was represented by dual power: the shogun had real power, the emperor - the “living god” - reigned but did not rule, his veneration was associated with the religious cult - Shintoism.

The basis of the administrative and economic structure of society were feudal principalities. The ruling princes, the overwhelming majority of whom were dependent on the Tokugawa house, were divided into categories according to income - according to the amount of rice collected in their possessions (rice was the main measure of values). The smallest feudal principality was considered to be the one that brought in an income of ten thousand koku of rice per year.

Lands in Japan were both state (possessions of the shogun) and private (possessions of princes, temples and monasteries). The peasants conducted independent farming on the basis of hereditary holdings. A characteristic feature of Japan's feudal production relations was the absence of open forms of serfdom. The feudal lord could not sell or buy a peasant, although there was a personal dependence - attachment to a plot of land determined by the feudal authorities.

The main form of land use was rent. The dominant form of duties was rent in kind - quitrent, but sometimes the feudal lord collected it in money. Labor rent (corvée) was not widespread in Japan, since for the most part the feudal lord did not manage his own household.

Features of the feudal development of Japan in the 7th–18th centuries

Date added: 2014-10-24 | Views: 1003Economic development of the United States in the second half of the 20th – early 21st centuries | Next page ==> Meiji transformations and their role in the Japanese economy

The formation of the feudal economy. Archaeological evidence suggests that the Japanese islands began to be settled in the 8th–7th millennia BC. e. But especially active migration to these lands began in the 4th–3rd millennia BC. BC: then the tribes of the Eastern Mongoloids moved to the islands, as well as various Altai and Malay tribes, from which the Japanese nation was subsequently formed. Until the 5th–4th centuries BC. e. The Neolithic Jomon culture (ceramic culture) existed on the islands .

The population was engaged in hunting, fishing, and gathering. Matriarchy dominated in tribal relations, gradually giving way to patriarchy.

In the V-IV centuries BC. e. the historical period of the Yayoi culture began ,

marking the transition to the bronze and iron stage of production. Irrigated agriculture and livestock farming appeared, and metal tools began to be used on farms. During this period, Japan was economically and culturally influenced by powerful migration flows from Southern China, Indochina, Manchuria, Korea and other Asian regions.

In the 3rd–5th centuries AD. e. the process of decomposition of tribal relations began , within which land plots were periodically redistributed between large families. Tribal leaders had so-called royal fields, which were cultivated by impoverished members of the community and slaves. Tribal leaders demanded that the community expand its power. They surrounded themselves not only with officials, but also with their own squad, consisting of professional warriors, since they were constantly faced with the need to protect their lands and conquer new ones. Yamato tribal union was created which by the middle of the 4th century united almost the entire country, except for the northeastern territories. On the basis of this union, the Japanese state began to take shape, the head of which was proclaimed the emperor.

In the 5th century, Chinese hieroglyphic writing penetrated the Japanese islands, and Buddhism spread in the 6th century

.

At the same time, representatives of the ancient and powerful Soga received senior positions at the emperor's court and began to pursue policies aimed at supporting the emerging feudalism. Quite in kind became widespread, which free community members had to pay to the state and wealthy landowners. Community members also had to participate in construction and irrigation work.

At the beginning of the 7th century, the process of strengthening centralized power noticeably intensified. As a result of complex intrigues, court circles led by Prince Nakanoe overthrew the power of the Soga family, and Emperor Taika became the head of state. His name is associated with the Taika reforms (645–654), which marked the transition to feudal orders and the formation of the early feudal centralized Japanese state. The final completion of the reforms occurred in 701, when the Taihoryo Code was drawn up, according to which all communal lands were confiscated in favor of the state, and peasants became only holders of state plots. These plots were redistributed between families within the community every 6 years. The land allotment per man was one third greater than that per woman, and the share of a slave was one third of the allotment of a free peasant. Large plots of land were allocated for special merits to officials, military personnel, relatives and favorites of the emperor. Large areas of land were owned by the imperial house and monasteries.

The state willingly encouraged the seizure and development of new lands by peasants, who in such cases were granted the right to private ownership by a special decree. These same peasants were exempt from taxes for a certain period of time. Taxes to the state were mainly paid in kind: rice, silk, etc. Peasants also had to work up to 100 days a year in government work. From 50 households it was necessary to send one recruit to the army. One of the forms of enslavement of peasants was rice loans, issued in case of crop failure or natural disasters from special state granaries. For the rice received, it was necessary to pay 30–50%, or even 100% of the total loan, and many peasants were unable to repay their loans.

…

It should be noted that in medieval Japan slavery

did not become the predominant form of economic management, although in the 8th century slaves made up 10–15% of the population here. They belonged mainly to the state and monasteries and performed hard work in the construction of huge imperial palaces, Buddhist temples, when laying roads, etc. By the end of the 8th century, slave labor had almost disappeared. It remained only in the household, where slaves were used as servants around the house or in auxiliary work.

In the 8th century, a new form of management began to emerge - the private estate, or shoen. This was facilitated by the widespread cultivation of rice, which required long-term labor costs and completely excluded periodic redistribution of land within the community. Land plots, or “named fields”,

assigned to individuals as private property. By the middle of the 10th century, shoen became the predominant economic entity in agriculture. “Named fields” turned into hereditary possessions, numbering from several tens to several hundred hectares.

The owners of such estates gradually began to claim significant independence from the state. By ceasing to pay taxes to the treasury, they declared disobedience to state laws and their immunity, that is, that representatives of state power were prohibited from appearing in their possessions. Shoen estates acquired a certain attractiveness in the eyes of the peasants, and this led to their mass unauthorized departure from state lands under the patronage of the landowners, who, in turn, gave them plots of land. In return, the peasants stopped paying state taxes and switched to a quitrent system in favor of the landowners, which turned them into feudal dependent people.

Shoen owners, striving for economic independence, created their own military squads to protect estates and suppress attempts by dependent peasants to move to other farms. Gradually, the warriors turned into a special closed class of warriors - samurai (bushi) - with their own code of honor, norms of behavior based on the principle of loyalty to their master. The strengthening of the economic independence of the Shoen led to feudal fragmentation and, as a result, to endless brutal internecine wars, which further weakened the centralized power in the country.

Socio-economic policy during the shogunate period. The largest and most influential feudal lords were considered the princes (daimyo), who especially revered their ancient origins. Many of them understood that the fragmentation of the country did not contribute to its prosperity, so from time to time there were attempts to unite Japan. At the end of the 12th century, this process was led by representatives of the ancient house of Minamoto. In 1192, one of the members of this family, Ioritomo Minamoto, having defeated Prince Taira in the struggle, proclaimed himself a military dictator, shogun, and power in the country took the form of a shogunate. Representatives of the first shogunate (Minamoto dynasty) ruled until 1333, transferring power by inheritance. At the same time, the Emperor of Japan retained only nominal powers.

During the reign of the Minamoto dynasty, a deliberate policy was pursued to weaken the economic power of large feudal lords, many of whom had their estates confiscated. The state distributed these lands to samurai - supporters of the shogun, who received the status of military nobles. Samurai did not receive land as full ownership, but in the form of fief, that is, conditional possession for the duration of their service. Thus, the samurai turned into the support of the shogunate. But since the samurai had to incur large expenses for military armor and weapons, many of them mortgaged and even sold their land plots. The authorities limited these operations, and in 1297 they completely prohibited the samurai from selling their lands.

…

Japan, due to its geographical location, did not experience serious external invasions in the Middle Ages. In particular, she managed to escape Mongol enslavement. In 1268 and 1271, ambassadors were sent from Mongolia to Japan demanding submission to the Mongols, but this mission ended in failure for them. In 1274, a powerful fleet containing about 30 thousand soldiers came close to the island of Kyushu, but a storm broke out and the death of the commander-in-chief contributed to the defeat of the Mongols. In 1281, another attempt was made to capture the Japanese Islands: this time the attack was carried out by the combined troops of Korea (40 thousand people) and South China (100 thousand people), but this attempt was not crowned with success.

At the beginning of the 14th century, internecine unrest broke out again with particular force in Japan, which the Minamoto dynasty could not cope with, and in 1333 the power of the first shogunate ended. For several years, the struggle continued between various factions of feudal lords, which led in 1338 to the proclamation of the second shogunate under the leadership of princes from the house of Ashikaga, who ruled until 1573.

It is known that back in the 12th century, a class system called shi-no-ko-sho , which determined the social and economic status of various groups of the population. The highest level in this hierarchy was occupied by secular feudal lords (the symbol “si”),

who owned land property and had the exclusive right to occupy the highest government and military posts.

Among them were court poets, artists, scientists, doctors, etc. This class also included military nobles - samurai (bushi).

The second most important estate was considered the peasantry (the symbol “but”),

which accounted for more than 80% of the total population. Formally, peasants were personally free people; they could not be bought or sold. At the same time, they could not freely change their place of residence and occupation. Peasants cultivated land that belonged to feudal lords, the imperial family or monasteries on a “perpetual lease” basis. The structure of feudal rent was dominated by quitrent in kind, reaching 40–60% of the rice harvest.

The third estate consisted of urban artisans (the symbol “ko”),

which was formed in the 13th–14th centuries, when crafts were finally separated from agriculture.

Among the townspeople there was also a fourth estate - merchants (the symbol “sho”).

Craftsmen and traders united into guilds (corporations), usually consisting of 10–50 people. All city dwellers were considered a lower class than peasants, although in terms of property status they were much richer. Often wealthy merchants could achieve samurai status.

By the end of the 14th century, great changes had occurred in the socio-economic structure of the country. The leading class once again became the owners of large feudal principalities (daimyo), who only formally recognized the power of the shogun, but in reality had almost unlimited rights within their estates. The daimyo purposefully sought to liquidate the small estates of the samurai military nobles. Samurai were forced to move to cities or return to the service of princes and settle in their castles. For their service they no longer received fiefs, but only rice rations. In some places, samurai turned into peasants and had to cultivate the princely lands.

In the 14th and 15th centuries there were noticeable changes in agricultural production. Thanks to improvements in agriculture, peasants began to harvest two crops a year in their fields: first they grew rice, and then, after harvesting it, they sown barley or wheat, which had time to ripen by autumn. Irrigation systems were created in dry fields. Bulls and horses began to be used for various types of work. In the 15th century, the cultivation of cotton and sugar cane began.

The urban economy was directly dependent on the development of agriculture. The spread of cotton culture led to the establishment of the production of cotton fabrics (along with the traditional production of silk fabrics). The state provided various assistance to artisans in the form of tax benefits, etc. In turn, many daimyo princes began to encourage the creation of craft enterprises on their estates. This trend especially intensified in the 16th century, when the class of “new daimyo” appeared, who invested not only in agriculture, but also in handicraft production, road development, and the construction of trade warehouses and shops. All this was in many ways reminiscent of the processes taking place in Western Europe, in particular in England, where at the same time a “new nobility” was being formed.

In the 15th–16th centuries, Japan began to actively enter the foreign market. At first these were trade relations with China and Korea. In 1542–1543 The Portuguese reached the Japanese shores, and in 1584 the Spaniards, who showed great interest in mutual trade. Christianity entered Japan with European merchants. During the same period, Europeans brought firearms to Japan, which the Japanese had not known until then.

…

It is interesting to note that in Japanese there is a word "rangaku"

translated literally as

“Dutch science”.

The fact is that it was the Dutch merchants, who received the monopoly right to settle in the city of Nagasaki before others, who had the greatest influence on the penetration of European culture into Japan.

But the country's political fragmentation hampered the development of the Japanese economy. Each principality had its own system of local taxes and customs duties; commodity exchange still prevailed in the country, in which rice was used instead of money.

The process of political unification intensified in the second half of the 16th century. It was led by the general Oda Nabunaga (1534–1582), the first of the three unifiers of Japan. In 1573, he overthrew the last shogun of the Ashikaga dynasty and began to vigorously implement reforms. First of all, Oda Nabunaga united 30 of Japan's 66 provinces. He then tried to eliminate internal customs outposts and streamline the tax system. The country began construction of national roads and bridges. Gold and silver coins were introduced instead of rice.

The active work of Oda Nabunaga aroused hostility among his opponents, who advocated the preservation of the old order. In 1582 he was killed. The work of Oda Nabunaga was continued by his associate Toyotomi Hwdeyoshi ( 1536–1598), the second unifier of Japan. In 1589–1596 A land reform was carried out, during which all land plots were entered into the cadastre. This made it possible to record the degree of land fertility and, in accordance with this, clarify the amount of taxes. In the villages, a “five-yard” system was created,

where all the peasants were bound by mutual responsibility. In 1591, a decree was issued strictly prohibiting peasants from leaving their plots without permission and going to other settlements.

At the turn of the 16th–17th centuries, the struggle for power intensified, and in 1603 the country was led by the third unifier of Japan, Ieyasu Tokugawa (1542–1616), who proclaimed himself shogun. From this time on, a new period began in the history of Japan - the third Tokugawa shogunate, whose representatives ruled until 1867.

However, the unification of the country was very relative. As before, the basis of the administrative and political structure of Japan remained the principalities, which formed the basis for the dictatorship of the shogun. The shogun's loyal defenders were the samurai, who received a rice ration for their service (later they began to be transferred to a cash salary).

Tokugawa led a decisive struggle against the European presence in the country. In 1614, Christianity was banned, then Tokugawa's successors began to expel foreigners from the country. In 1623–1624 The British and Spanish left Japan, and by 1639 all the Portuguese were expelled from it. Of the Europeans, only representatives of Holland could still conduct some trade operations, but their number was constantly decreasing. New laws (1635) prohibited the Japanese from leaving the country, as well as from building ships with a displacement of over 80 tons. Only small junk boats from China could sail to the shores of Japan.

By the 18th century, Japan strengthened foreign trade restrictions and headed for international self-isolation. Only a few cities on the west coast of Kyushu remained relatively open. Thus, Dutch ships were allowed to enter the port of Nagasaki twice a year. In fact, it was a form of government control over foreign trade. Attempts by some large countries to “open up” Japan to sell their goods remained unsuccessful.

During the period of the third shogunate, the class system shi-no-ko-sho became stricter, according to which people’s behavior was extremely regulated. There were especially many restrictions for peasants: they were forbidden to drink rice and rice vodka, smoke tobacco, wear silk clothes, hold lavish festivities, go on visits, etc. Special officials monitored their behavior.

A strict daily routine was established for the peasants. For example, in the morning they all had to mow the grass together, then work in the rice fields, and in the evening weave mats and bags. In addition, they paid a large rent. And although there was a principle “four parts for the prince, six for the people”

(i.e., the size of the quitrent was determined at 40% of the harvest), the real amount of taxes in favor of the feudal lords reached 70% of the gross harvest.

But tax collectors, who were constantly looking for new objects of taxation, committed particular arbitrariness towards the peasants. In addition to land plots, taxes were levied on windows and doors of houses, silk and cotton fabrics, rice vodka, beans and hemp crops, nut and fruit trees and much more.

Peasants also had to carry out postal service and supply horses for state transport (horse-drawn duty). They were still obliged to work a certain number of days a year on the construction of imperial palaces, temples, bridges, roads, and irrigation systems. Among the Japanese peasants there were many very poor people who “drank water”

people who did not have sufficient means of food. Many of them tried to mortgage or sell their plots to merchants and moneylenders at high interest rates, but in 1742 a decree appeared prohibiting such transactions.

The peasants abandoned their land and went to the cities, but even there there was no particular chance of escaping poverty. Japan was rocked by peasant revolts. During the third shogunate, 1,163 uprisings and “rice riots” occurred in the country, which undermined the foundations of feudalism.

At the same time, there was a process of impoverishment and declassification of the samurai, whose rice rations were constantly reduced by the princes, and they fell into debt dependence on moneylenders. To pay off debts, samurai mortgaged their own weapons, land plots, and even sold their rank. The “nobles of the sword” were obliged to switch to the position of small land tenants, ronins, and engage in crafts or trade. But the samurai refused such activities, considering it a humiliation of their honor, and went into the forests, where they created armed groups that traded in robbery.

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | 31 | | | | | | | | |

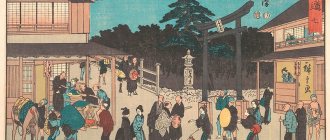

Japanese culture in modern times (16th-18th centuries)

Art has always played a special role in the life of the Japanese. The desire to feel harmony with the world around us, the ability to see beauty around oneself, even in ordinary things, are natural traits of the Japanese character.

In the XVI-XVIII centuries. Ensemble architecture flourished, in which the castle and the garden located around it were combined into a common whole. Castles with multi-tiered curved roofs resembled birds soaring in the sky.

In the gardens, artists so skillfully placed trees, bushes, stones and streams that their contemplation created a feeling of peace and detachment from everyday bustle.

Japanese artists decorated the palaces of rulers and nobility with wall paintings, and painted ink drawings on silk and paper scrolls and exquisite fans. Screen paintings, which served as decorative partitions between rooms, were also highly valued.

A popular type of painting was engraving - a printed impression of a design applied to a wooden board or metal plate. They depicted actors in theatrical characters, Japanese beauties and scenes from everyday life.

Since the 17th century Netsuke - small figurines made of wood, stone, ivory, and porcelain - came into widespread use among the Japanese. Their appearance is due to the fact that the national Japanese costume, the kimono, has no pockets.

Therefore, all the necessary small items (keys, wallet, medicine box, pipe) were attached to the belt using a netsuke keychain. Since the 18th century famous masters began making netsuke, and since then they have turned into works of decorative art.

Netsuke was made in the form of gods, good spirits, animals; they were considered talismans that brought good luck.

The Japanese believed that poetry was invented by the gods, therefore it is more important than prose - a human invention. Poets wrote short poems without rhyme, but every word in them had a deep meaning.

The Japanese theater, where the actors were only men, was popular.

From the 16th century The art of arranging flowers in vases - ikebana ("life of flowers") received special development. Famous masters created different types of ikebana, always putting a certain content into them.

Each plant embodied a specific wish: pine and rose - longevity, peony and bamboo - prosperity and peace, chrysanthemum and orchid - joy. It became a custom to train girls in the art of arranging bouquets.

The tea ceremony occupies a special place in Japanese culture. From the 16th century it turns into real art.

Everything mattered here: the location of the tea pavilion and the garden around it, the choice of ikebana and dishes, furnishings and every gesture of the owner.

Japanese culture XVI-XVIII centuries. everything is permeated with the desire to find harmony in the relationship between man and nature. She is filled with the desire to see beauty in both the big and the small.

New Heaven // New Heaven – Simon Khorolskiy & Friends (Original Song)

You can also read…

- Japanese attack on China. liberation philippines

- Japan self-isolation (sakoku)

- Culture and science of ancient Greece during the Hellenistic era

- The flourishing of culture at the court of Charlemagne

- Christianity and culture in the Middle Ages

- Culture and spiritual life of Trypillians