The Japanese writing system consists of two types of signs: syllabic alphabet - hiragana (平仮名) and katakana (片仮名), as well as hieroglyphs (漢字), which came to Japan from China. Each of these types of characters has different purposes and characteristics, but they are all used in Japanese writing.

Most Japanese texts contain combinations of hiragana and characters, creating a unique system. Hiragana and katakana are unique to the Japanese language, and we strongly recommend that students first master these two alphabets before starting to study Japanese in Japan.

Due to the varied use of three different types of characters, the Japanese written language is considered one of the most difficult to master.

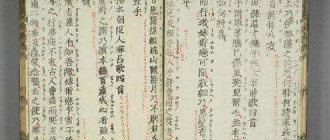

Japanese characters can be written vertically and read from top to bottom, left to right, as is customary in traditional Chinese writing, or they can be written horizontally, read from left to right, as in Russian.

Hiragana

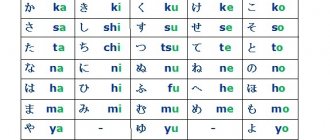

Hiragana, which literally means "ordinary" or "simple" kana, is used primarily for native Japanese words and grammatical elements. There are 46 basic characters that represent syllabic marks, or 71 characters if counted together with diacritics. Each sound in Japanese corresponds to one character in the syllabary. Typically, students learn hiragana first, followed by katakana and kanji.

Hiragana is also used for furigana (ふりがな) or yomigana (読み仮名), small characters that reflect the pronunciation of characters written above or next to them. It helps to read a character that you may not yet know, so initially you need to master kana as best as possible! Books intended for young children are often written only in hiragana.

Hiragana is also used to write okurigana (送り仮名) - endings after the main character, which can reflect the meaning of verbs and adjectives, grammatical constructions and Japanese native words that do not have characters or if the characters are too complex. These basic Japanese syllabic characters can also be modified by adding the sign dakuten (濁点) - (゛) or handakuten (半濁点) - (゜).

This can all be a little confusing, but don't worry—the longer you study Japanese, the easier it will be to remember the alphabet. However, to get started, it may be helpful to use an app like Hiragana Quest . It uses mnemonics that make symbols easier and easier to remember. Find out more about the app here!

Accent

Typically, Japanese words, titles and names in Russian are pronounced with emphasis on the penultimate syllable, and such emphasis is generally preferable in doubtful cases. However, there are a number of exceptions, in particular:

- Words ending in “on”

,

“an”

,

“mono”

and

“ko”

(in three-syllable words) are pronounced with emphasis on the last syllable:

“ippOn”

,

“jomOn”

,

“kimonO”

,

“nuriko”

, but

“ heiko"

,

"tenno"

,

"nagano"

.

If the ending is “en”

, you can do both (

seinEn

-

seinen

). - Words ending in diphthongs “ai/ey/ui/oh”

are pronounced with emphasis on the last syllable:

“sensei”

,

“samurai”

,

“bankey”

. - The emphasis cannot fall on “u”

and

“i”

standing between two voiceless consonants.

In this case, it is transferred to the second syllable from the end (if there is one), or to the last syllable: “Asuka”

,

“sukA”

,

“tasuki”

,

“tEzuka”

,

“fukU”

. - If the last syllable of a Japanese word is long, then the stress falls on it, even if the longitude of the syllable is not conveyed in the spelling: "maho"

. - The word “Tokyo”

is pronounced this way according to tradition (actually, the more correct spelling is

“Tokyo”

). - Words containing one syllable with “е”

can be pronounced with emphasis on this syllable (according to the general rule of Russian stress):

“aUm shinriyo”

(“Aum” is not a Japanese word and is pronounced according to different rules).

Unfortunately, I have not yet been able to find an authoritative source describing the rules for forming the pronunciation of Japanese words in Russian. In this regard, I formulated the above rules based on an analysis of historically established pronunciation among otaku. ^_^

Katakana

Katakana, which means "fragmentary kana", is used mainly to write foreign words and names, loanwords and words of onomatopoeia. Some of the most useful Japanese words are untranslatable onomatopoeias , such as ギリギリ (girigiri), which means “extremely, extremely,” which is used when, for example, running through the closing doors of a train at the last minute or being on time for class to start in a second.

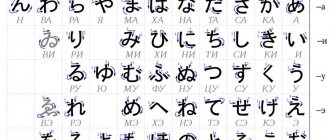

Like hiragana, katakana has 5 vowels, 40 syllables and 1 consonant. Often you'll see both hiragana and katakana in a 5x10 chart called gojuon (五十音) or "fifty sounds."

The use of katakana is sometimes similar to the cursive in English used to transcribe foreign words in Japanese. Gairaigo (来語), or loanwords, are all written in katakana, such as バナナ for banana. Foreign names are also written in katakana.

Recording system competition

One of the main modern forms of novelization that international students study is the Hepburn system. It is named after the American missionary James Curtis Hepburn, who popularized it for the third edition of the Japanese-English dictionary, published in 1886. Although the system is named only after him, it was actually developed by a group of Japanese and foreigners, Romajikwai, the "Latin Script Society", of which he was a member. It subsequently went through a number of modifications, and is now sometimes called the modified Hepburn system.

Another important romanization system is Kunrei, based on the earlier Nippon system. While Hepburn aimed to make Japanese words easier to pronounce for readers familiar with English, Kunrei is a more regular and easy-to-use system aimed at native Japanese speakers. Foreign students are accustomed to the irregularities of the Hepburn system, which is clearly seen in the series “ta”: ta, chi, tsu, te, to, while in Kunray the same syllables are written as ta, ti, tu, te, to.

Examples of romaji differences in the Hepburn and Kunray systems

| Hepburn | Kunray | |

| し (si | shi | si |

| じ (ji | ji | zi |

| ち (ti | chi | ti |

| つ (tsu | tsu | tu |

| ふ (fu | fu | hu |

| しゃ (xia | sha | sya |

| じゅ (ju | ju | zyu |

Perhaps the Hepburn system is by far the dominant one among foreigners and guests of the country living in Japan. It can be found not only in language materials, but also in official contexts - for example, in the names of places on signs and road signs. However, Kunrei is still taught in some primary schools, and there students write Huzi rather than Fuji. They begin studying the Hepburn system, which is considered more complex, already in middle school.

Even within Hepburn's system, there is disagreement about how to produce certain sounds. For example, long "о" (о: in Cyrillic transliteration may be written as "ō", "o", "ou", "oh" and "ô". Some prefer to display the actual pronunciation of "n" before some consonants as "m" ", as in Shimbashi (Nippon.com's English version uses macrons such as "ō" and "ū" to indicate vowel length, and sticks to the "n" spelling, with some exceptions.

Hieroglyphs

Only a few thousand hierogyphs are used regularly. They all have different meanings, and most have more than one pronunciation depending on the context. For example, 今日 can be read as kyō, meaning “today,” or as konnichi, meaning “lately.”

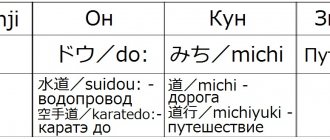

Character readings are divided into on'yomi (音読み, おんよみ), which is a "sound reading" derived from Chinese, and kun'yomi (訓読み), which is the original Japanese "meaning reading". Most hieroglyphs have at least one of these, and some have several.

In Japanese elementary, middle and high schools, students learn more than 2,000 jouyou kanji (常用漢字), regularly used characters. Interesting fact: the same number of hieroglyphs is required to successfully pass the highest level of JLPT. Although there are over 50,000 characters, most Japanese do not know them all.

In fact, there are no universal tips for memorizing hieroglyphs - you must learn and remember each character along with its reading. Studying in Japan , where you will use Japanese every day, can really help You'll remember how words are read and used much faster than if you learned Japanese in your own country.

LiveInternetLiveInternet

Kanji Kanji (漢字, lit. "Han Dynasty Letters") are Chinese characters used in Japanese writing primarily to write nouns, stems of verbs and adjectives, and Japanese proper names. The first Chinese texts were brought to Japan by Buddhist monks from the Korean kingdom of Baekje in the 5th century. n. e.. Today, along with native Chinese characters, signs invented in Japan itself are used: the so-called. kokuji. Depending on how kanji entered the Japanese language, characters can be used to write the same or different words or, more often, morphemes. From the reader's point of view, this means that kanji have one or more readings. The choice of reading for a character depends on the context, combination with other kanji, place in a sentence, etc. Some commonly used kanji have ten or more different readings. Readings are generally divided into onny readings, or on'yomi (Japanese interpretations of the Chinese pronunciation of the character) and kun readings, or kun'yomi (based on the pronunciation of native Japanese words). Some kanji have multiple on'yomi because they were borrowed from China several times: at different times and from different areas. Some have different kun'yomi because there are several Japanese synonyms for the Chinese character. On the other hand, a kanji may not have any onyomi or kunyomi. Rare readings of hieroglyphs are called nanori. Nanori is widespread in proper names, in particular surnames. There are many kanji combinations that use both on and kun to pronounce their constituents: such words are called zubako (重箱) or yuto (湯桶). These two terms themselves are autological: the first kanji in the word zubako is read according to onu, and the second - according to kun, and in the word yuto - vice versa. Other examples: 金色 kin'iro - “golden” (on-kun); 空手道 karatedo: - karate (kun-kun-on). Gikun (義訓) - readings of kanji combinations that are not directly related to the kuns or ons of individual characters, but related to the meaning of the entire combination. For example, the combination 一寸 can be read as issun (that is, “one sun”), but in fact it is an indivisible combination of tetto (“a little”). Gikun is often found in Japanese surnames. For all these reasons, choosing the correct character reading is a difficult task for Japanese language learners. In most cases, different kanji were used to write the same Japanese word to reflect shades of meaning. For example, the word naosu written as 治す would mean “to treat a disease,” while the word spelled 直す would mean “to repair” (such as a bicycle). Sometimes the difference in spelling is clear, and sometimes it's quite subtle. In order not to be mistaken in shades of meaning, the word is sometimes written in hiragana. About 3 thousand hieroglyphs are actively used in modern written language. 1,945 kanji constitute the required minimum taught in schools. From kanji came two syllabary alphabet - kana: hiragana and katakana.

Hiragana Hiragana (Japanese: 平仮名?) is a syllabary alphabet, each character of which expresses one mora. Hiragana can be used to express vowel sounds, syllable combinations and one consonant (n ん). Hiragana is used for words that cannot be written in kanji, such as particles and suffixes. It is used in words instead of kanji in cases where it is assumed that the reader does not know some hieroglyphs, or these hieroglyphs are unfamiliar to the writer himself, as well as in informal correspondence. Forms of verbs and adjectives (okurigana) are also written in hiragana. In addition, hiragana is used to write phonetic clues for reading characters - furigana. Hiragana originated from Man'yogana, a writing system that emerged in the 5th century AD. e., in which Japanese words were written in similar-sounding Chinese characters. Hiragana characters are Man'yogana written in the Caoshu style of Chinese calligraphy, so the characters in this alphabet have rounded outlines. Previously, in Japanese texts there could be different hiragana styles for the same mora, derived from hieroglyphs with the same reading, but after the reform of 1900, one character was assigned to each mora, and a set of alternative styles began to be called hentaigana, which is used to a limited extent to this day day. At first, hiragana was used only by women who did not have access to a good education. Another name for hiragana is “women's writing.” Genji monogatari and other early women's novels were written primarily or exclusively in hiragana. Today, texts written only in hiragana are found in books for preschool children. For ease of reading, such books have spaces between words. Katakana (Japanese: 片仮名?) is the second syllabary of the Japanese language. Allows you to convey the sound of the same moras as hiragana. Used to write words borrowed from languages that do not use Chinese characters - gairaigo, foreign names, as well as onomatopoeia and scientific and technical terms: names of plants, machine parts, etc. Semantic emphasis on the word or section of text in which they are usually used kanji and hiragana can be created by writing it in katakana. Katakana was created by Buddhist monks in the early Heian era from man'yogana and was used as phonetic clues (furigana) in kambun. For example, the letter ka カ comes from the left side of the kanji ka 加 “to increase.” In part, katakana corresponds to a key system for kanji with the same pronunciation. Katakana characters are relatively simple and angular, some of them resemble similar hiragana characters, but only kana “he” (へ) is completely identical. Romaji Rōmaji (Japanese: ローマ字 lit.: “Latin letters”?) - writing Japanese words in Latin letters. Used in Japanese language textbooks for foreigners, in dictionaries, and on railway and street signs. Japanese titles and names are written using romaji so that they can be read by foreigners, such as on passports or business cards. Some abbreviations of foreign origin are written using romaji, such as DVD or NATO. Romaji is widely used in computer technology: for example, keyboards often use the kana input method (IME) through romaji. There are several romanization systems for the Japanese language. The earliest system of romanization of Japanese was based on the Portuguese language and its alphabet and was developed around 1548 by Japanese Catholics. After the expulsion of Christians from Japan in the early 17th century, romaji fell into disuse and was used only sporadically until the Meiji Restoration in the mid-19th century, when Japan reopened to international contact. All current systems were developed in the second half of the 19th century. The most common is Hepburn's system, which is based on English phonology and gives Anglophones the best idea of how a word is pronounced in Japanese. Another system is recognized as the state standard in Japan - Kunrei-shiki, which more accurately conveys the grammatical structure of the Japanese language. Writing Direction Traditionally, Japanese has used the Chinese vertical writing method, 縦書き (たてがき, tategaki, literally “vertical writing”)—characters run from top to bottom and columns from right to left. This method continues to be widely used in fiction and newspapers. In scientific and technical literature and in computers, the most commonly used European method of writing is 横書き (よこがき, lit. “side writing”) - characters go from left to right, and lines from top to bottom. This is due to the fact that in scientific texts it is very common to insert words and phrases in other languages, as well as mathematical and chemical formulas. This is very inconvenient in vertical text. In addition, there is still no full support for vertical writing in HTML. Officially, horizontal writing from left to right was adopted only in 1959; before that, many types of texts were typed from right to left. Today, although very rarely, you can find horizontal writing with a right-to-left direction on signs and slogans - this can be considered a subtype of vertical writing, in which each column consists of only one character.

vertical Japanese letter horizontal Japanese letter

Romaji

In addition to the three writing systems in Japan, one can also see the Latin alphabet used to represent sounds. Rōmaji (ローマ字) can be used when Japanese text is intended for non-Japanese speakers, such as on street signs, dictionaries, textbooks, or passports.

Romaji is also used when typing on a computer. Although Japanese keyboards are capable of typing using kana, many people use the Roman alphabet to type syllables for later input of Japanese characters.

At the initial stage of learning hieroglyphs, romaji will help you read Japanese words.

Updates to this word to transcription translator

Major update to the translator of Japanese characters into transcription

Over the past few weeks, we have been working hard to improve the Japanese word to transcription translator. Here is a list of the most important updates: The quality of the translation of hieroglyphs into transcription has been significantly improved. Now the tonal stress is marked in.

English translation of words in Japanese character translator

Another update in the Japanese text to transcription translator. Now, after you have sent the Japanese text, you can click on a word to see its English translation. We used.

Updates in the translator of Japanese words into transcription

The algorithm for translating Japanese characters into Romaji has been improved: Now the resulting transcription can be copied/pasted into other programs. It took me a while to figure out how to do this. When copying, the transcription of Japanese words is very important.

Support for the international phonetic alphabet in the translator of Japanese characters into transcription

I have added an option that allows you to convert Japanese text to International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) characters in the Kanji to Romaji translator. At first I wanted to use the IPA table from the Japanese Sanseido dictionary, but...

Source

Get the basics with Go! Go! Nihon

Such a complex system of characters can be a little intimidating, especially for those who are just starting to learn Japanese. But don't worry, there are plenty of great resources for learning language alphabets and characters, from books to phone apps to games!

If you're learning Japanese at home, we have some great articles that might help you: *Best apps for learning Japanese *Self-isolating? Use this time to learn Japanese!

Another great way to learn the basics of Japanese is to take our online course for beginners . We have worked in partnership with Akamonkai Japanese Language School to offer a comprehensive 12-week course, providing a solid foundation of knowledge to develop your language skills. You can find out more about the course here.

For more information, don't hesitate to contact us!

Rules for converting Kunrei Romaji to Kiriji

Vowels

| a - a | i - and | u - y | e - e | o - o |

| ya - I | yu - yu | yo - ё | ||

| ai - ah | ui - ui | ei - hey | oi - oh |

Syllables

| ka - ka | sa - sa | ta - that | na - on | ha - ha | ma - ma | ra - ra |

| ki - ki | si - si | ti - ti | ni - neither | hi - hee | mi - mi | ri - ri |

| ku - ku | su - su | tu - tsu | nu - well | hu - fu | mu - mu | ru - ry |

| ke - ke | se - se | te - te | ne - ne | he - he | me - meh | re - re |

| ko - ko | so - with | to - then | no - but | ho - ho | mo - mo | ro - ro |

| wa - wa | n - n | pa - pa | ba - ba | da - yes | za - dza | ga - ha |

| pi - pi | bi - bi | di - di | zi - dzi | gi - gi | ||

| pu - pu | bu - bu | du - du | zu - dzu | gu - gu | ||

| pe - pe | be - bae | de - de | ze - ze | ge - ge | ||

| wo - about | po - according to | bo - bo | do - before | zo - dzo | go - go |

Combinations

| kya - kya | kyu - kyu | kyo - kyo | mya - me | myu - mu | myo - me |

| sya - sya | syu - syu | syo - syo | rya - rya | ryu - ryu | ryo - ryo |

| tya - you | tyu - tyu | tyo - you | gya - gya | gyu | gyo - gyo |

| nya - nya | nude - nude | nyo - not | zya - dzya | zyu - ju | zyo - jo |

| hya - hya | hyu - hyu | hyo - hyo | bya - bya | byu - byu | byo - byo |