Marry a foreigner

Today we will touch on the topic of relations between men and women in Japan. Let's start with family traditions and foundations.

Traditions and foundations

Men in this country, for the most part, do not like and do not consider it necessary to do housework. Japanese women unanimously confirm that the typical Japanese man is the kind of person who doesn’t want to hear anything about housework at all. It turns out that from childhood boys are raised by their mothers in such a way that women always do everything around the house.

Pupils

Be it your mother, older sisters or a housekeeper, who is often hired by Japanese families. In Tokyo or other big cities, family servants who do cleaning, cooking, and other housework are considered the norm. In any case, this is done by a woman from the family or for hire.

When it comes to money, Japanese husbands believe that providing for the family financially is 100% a man's task. Although almost all women in this country work, the financial well-being of the family rests on the shoulders of the husband.

And if suddenly there is not enough money for something, then the head of the family will never send you to work, much less, to look for additional part-time work. The man himself will solve this problem. In any city in this country, people love to live well, denying themselves almost nothing.

Tokyo

The existing monetary paradigm, as a model of successful existence, is considered the norm in Japan. Therefore, the Japanese spouse strives to earn as much as possible and provide for the material side of his family as best as possible. As for a woman, she can even go to a low-paid job in order to devote more time to raising children.

Submissive attitude of a woman

The next fact of the relationship between husband and wife in the family is the woman’s somewhat subordinate attitude towards her husband. This is not to say that Japanese men do not respect women. As for respect, it’s just the opposite; the Japanese are very respectful of each other, women, old people, etc. This quality is instilled in young citizens of the Land of the Rising Sun from childhood.

For example, when acquaintances meet, they greet each other with a bow. In general, the Japanese are very polite. And if the husband politely asks his wife to bring him slippers, then she must obey, since she considers it her duty, this is how girls are raised from childhood. In this case, refusing is not accepted or, to put it mildly, is considered rude. Even while sitting in a restaurant, the wife pours sake for the man, and not vice versa.

Marry a foreigner

Oddly enough, with such a high standard of living (the average Japanese salary is $3,000), many Japanese girls want to marry a foreigner. Because the women of this country are not satisfied with their subordinate position, and not only in the family.

For example, a Japanese woman cannot be the leader of a male team. She is allowed a higher position only among women. And highly paid positions are primarily occupied by men. Therefore, progressive women in Japan want to have a European version of family and family relationships.

Japanese woman: discrimination - or?

A LITTLE HISTORY

We can safely say that until approximately the end of the 11th - beginning of the 12th centuries, the position of women in Japan was at a very high level: they had the same rights as men in matters of marriage, labor and even inheritance of property, albeit with some reservations. The reasons for this lay partly in the Shinto religion - after all, the eight million deities who lived in Japan were ruled by the supreme goddess Amaterasu - partly in the fact that the privileged class in the Nara and Heian periods (VIII-XII) were not the ruler’s close warriors, but government employees.

In the 12th century, the samurai began to strengthen as a class, which contributed to the formation of a military elite and the weakening of the positions of officials. In addition, Buddhism, which postulated the superiority of men over women, finally became part of Japanese culture. All this led to a decrease in the role of women in the social and labor spheres.

This trend reached its apogee towards the end of the 16th and beginning of the 17th centuries. At the same time, Confucianism became the official religion of the Tokugawa shogunate, which ordered a woman to obey her father in childhood, her husband in adulthood, and her son in old age. This determined the subordinate position of women in the ruling class, their proper place. She was supposed to become an elegant, caring, responsible, quiet and submissive housewife - an adornment to her father or husband. And she, deprived of the right to self-determination, took on this appearance. And this same appearance subsequently affected the image of other Japanese women.

But here it is also necessary to mention that this state of affairs was observed exclusively in samurai families, while in all other classes the position of women was not so depressing. Thus, despite the influence of Buddhism, women of other castes in Japan at that time retained considerable rights: among peasants and artisans, for example, marriages were much more often by the consent of the bride and groom themselves. Although in families of these castes the position of each family member was differentiated, and women occupied a different, lower position than men.

This state of affairs continued until the end of the 19th century, until the reforms of the Meiji Restoration. One of the consequences of the accompanying changes was the elimination of caste boundaries, which previously not only established a hierarchy of subordination to the military elite, but also served as a kind of guarantor of the preservation of the customs and traditions of each social stratum. Now, during the Meiji era, samurai values and customs began to permeate the entire society.

Thus, all women were assigned the role of a housewife, a kind of prisoner of their own home - discrimination, which had previously been a feature of only one caste, became the lot of everyone. And taking into account the ever-increasing militarization of the Japanese Empire, it became obvious exactly what place a Japanese woman should have in a state of this kind. One can even make the assumption that it was during this period that more polite and respectful forms of women addressing men and more familiar forms of men addressing women were finally established.

All this lasted until the end of the Second World War, when the defeated Japan was forced to accept gender equality in the 1946 Constitution, and in 1947 adopted amendments to the Civil Code, according to which women received the same legal rights and responsibilities in all areas of life as and men. These provisions were confirmed by the Equal Opportunity Bill of 1986.

However, the discrimination inherited from militarized Japan has not completely disappeared: there are still a large number of problems in the work and everyday spheres of life. It is more difficult for a woman to get a job in general, and even more difficult to get one under the same conditions as a man. In the domestic sphere, a significant part of the household responsibilities falls on the woman, even if both she and the man work. Taking care of the children in the family falls entirely on the shoulders of the wife, since fathers of families often disappear until late at work. And at times, husbands do not see their relatives for weeks due to the peculiarities of Japanese labor policy: promotion in a number of Japanese companies means not only the acquisition of new powers, but also a “movement” at the place of work to another place, often even to another province.

FAMILY VALUES

In general, if we touch on the family issue, here we can note several trends characteristic of Japan.

Firstly, throughout the 20th century there was a gradual decline in families of the traditional type and the growth of families of the nuclear type. The same trend is true for this century. In addition, it should be noted that the number of love marriages based on personal affection is gradually, albeit slowly, growing. And this growth is gradually replacing arranged marriage, which held families together rather than hearts.

Media news2 Secondly, there is a gradual aging of the nation due to later marriage. And if at the end of the 20th century the average age for a girl to get married was about twenty years, then already in the early years of the 21st century it approached the mark of thirty years. Accordingly, the birth of children occurs at approximately thirty-two to thirty-four years of age.

Thirdly, marriage itself has ceased to be mandatory, even the pressure from society on women in this regard has become much less. And it is no longer surprising for a woman to choose career growth rather than the role of a housewife, although the number of the latter is still very high. Most likely, this is also partly due to the fact that if for a man starting a family is a kind of fulfillment of a duty towards his parents, which he almost never fulfills after the wedding, then for a woman this is a much more serious step. After all, for her the question arises: either a household or a career.

Fourthly, women who have given up career development quite often become so-called “kyoiku mama”, women for whom helping their children in their development becomes a top priority. Their motherhood makes life “ikigai” meaningful for them, and they correlate the subsequent periods of their lives with the periods of their children’s lives: kindergarten, school, university.

However, not everything is as simple as one might think. Despite giving up a career, many housewives still spend at least part of their motherhood working. Temporary hiring and part-time work are a common type of employment for those married women who, although they prefer family to work, still do not limit their range of interests exclusively to household chores.

There is also another interesting feature of family relationships between husband and wife: despite the fact that in the overwhelming majority of cases it is the man who provides for the family, the wife manages the budget of this institution. There are even families where a man’s salary is immediately transferred to his wife’s bank account, making him virtually a hostage to his wife’s decisions in the economic sphere.

GENDER DISCRIMINATION

Similar ambiguity in the relationship between men and women is also present in other areas, forming discrimination not only against women, but also against men.

For women, these are most often problems with getting a job. Moreover, problems can arise in many cases. It is more difficult for women to get a job in general, and a decent job in particular. But even if you get a decent position, it is possible that the salary will be paid less than a man in a similar position. Also, women are often forced to resign of their own free will instead of taking maternity leave. In other words, most often discrimination against Japanese women lies in the labor sphere, which, given their increased political and trade union activity, is perceived extremely painfully by them.

The oppression of men concerns other areas. Just as there are carriages in the metro exclusively for women, there are cafes only for women, and even libraries. There are also serious differences in payment for certain services: in some cases, medicine and some goods cost more for men than for women. In addition, in public institutions there are so-called “Lady's days”, when women are entitled to large discounts, for example, on some days, cinema tickets for Japanese women are almost half the normal price. There are no such services for men.

Based on all this, we can conclude that each gender is subject to certain oppression, but in different areas of life, as a result of which both men and women acquire special “rights” and “penalties” that determine their social reality.

If we summarize both discrimination and differentiation of labor in the context of the history of sexual relations on the territory of present-day Japan, then we can understand that the current state of affairs - the political and social activity of women, the aging of the nation and the growth of nuclear families - is a consequence, on the one hand, of historical processes , and on the other, a cultural phenomenon in which the role of women, initially high, was gradually reduced to a minimum. Now, on the contrary, representatives of the fair sex have the opportunity to demonstrate civic activity, despite the outward humility manifested in etiquette and speech patterns.

Relationships between men and women in Japan

Historical reference

The nature of the relationship between a man and a woman in Japan changed in accordance with the dominant social structure of society in a given period and the position of women determined by it. In the distant past, Japan was a matriarchal society in which women had inheritance rights to family property. Those times produced many women leaders. In everyday life, men and women appeared to enjoy equal social, political and economic rights.

Even after men began to occupy dominant positions in society during the Nara and Heian periods, relatively equal relations remained among ordinary people, while in aristocratic circles men usually had greater power over women. By the end of the Heian period, women's inheritance rights had weakened significantly, accelerating their economic subordination to men.

The most important feature of the Middle Ages, known as the Kamakura and Muromachi periods, was the development of the ie system, which gave the dominant role in politics and society to men. Ie literally means "house" in a dual sense - as a residential building, structure, and as a family, a community of people living together, as well as their household. The Ie way of life assumed an expanded family system, covering not only members of one family, but also their servants, hired workers, helping with housework, etc. In such a system, the eldest man (ie the father or grandfather) had enormous power, and other family members were obliged to carry out his orders. Usually, women who married the head of the family were expected to have a son, since in the patriarchal system the first son received inheritance rights and was assigned an important role in maintaining and preserving the clan. This concentration of power in the family helped to care for all its members and reflected a similar structure of government. Japanese society of that time was characterized by a developed class-class system, in which the samurai assigned women an important connecting role within the framework: through the twinning of different surnames [clans], their political power was achieved and maintained. Women were not only expected to obey their husbands, but also to be strong, as warrior wives should be, so that they could support their husbands and lead the home when they went to war.

Relationships between men and women began to change significantly during the Edo period, when Confucianism, which became the official religion of the Tokugawa shogunate, had a huge influence on the formation of the Japanese national character. Many ideas of the teachings of Confucius have become widespread, incl. the position of “a man outside and a woman inside,” which is still observed in Japanese society (a man deals with all the affairs of the external environment: politics, work, a woman’s responsibility is home and family).

The next stage of change in gender relations began with the introduction of compulsory education for men and women during the Meiji period, when Japan rapidly and assiduously borrowed and assimilated Western ideas. However, education for men and women was far from equal, partly because the main purpose of women's schools was to specifically educate ryōsai-kembo (literally: "good wives and wise mothers"). Classes in women's schools were focused mainly on housekeeping, in which women were supposed to help their husbands and be able to raise and teach their children everything they needed. It was only after World War II that all Japanese, regardless; from gender, received equal rights guaranteed by the new constitution of the country. Additionally, the Equal Employment Opportunity Act was passed in 1986 to eliminate discrimination against women in the hiring process. Thus, the position of women in society has gradually strengthened, but it is also true that discrimination is still common despite changes in the law.

Relationships between Japanese men and women have been undergoing rapid changes recently. More women than ever before are working outside the home; Views on the norms of gender relations have changed, as well as on the institution of marriage. These changes are visible from a variety of perspectives, which we will explore below, using Japanese terms that reflect changes in the approach to marriage and marital relationships.

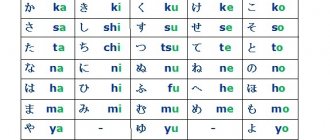

Japanese expressions referring to women.

Japanese women's position in society is still more dependent than in most Western countries. This is increasingly noticeable against the background of the growing internationalization of the world. The reason why women have difficulty establishing their social positions seems to be due to the influence of Confucianism, which continues to have a strong, although not always recognized, influence on the Japanese. For example, an old Confucian saying states that a woman should obey her mother in her youth, her husband in adulthood, and her son in old age. The structure of the Japanese language clearly reflects these nuances of relationships between men and women. When addressing their husbands, most wives use the word shujin, which consists of two characters meaning “master; main man." On the other hand, in relation to their wife, men are content with the word kanai, which literally means “inside the house.” These expressions very well illustrate the stable traditional Japanese concepts of the family, according to which husbands are more important than wives, and the latter must always be at home, manage the household and obey their husbands. Similar concepts can also be seen in the order of the hieroglyphs that form the compound words that define heterosexual groups: danjo (man and woman), fufu (husband and wife), etc. — everywhere the “male” hieroglyph comes first.

There are a lot of expressions in the Japanese language that are used only to refer to women, making fun of them or telling them how they should behave. Here are just three examples: otoko-masari, otenba and hako-iri-musume. Otoko-masari means a woman who is physically, spiritually and intellectually superior to a man. But the literal meaning of the expression “a woman who is superior to a man” often takes on a negative connotation in Japanese, since it also carries the additional meaning of a lack of femininity (compare the Russian expression “boy-woman”), and such women are usually disliked. Otemba can be translated into Russian as “tomboy girl,” which is the name given to lively and active teenage girls. Parents often say othemba about a daughter who is so energetic that they cannot cope with her. Such a girl, however, is expected to become more modest and docile with age. Hako-iri-musume can be translated as “daughter in a box.” This expression refers to a daughter who is treated very carefully by her parents, as if she were some kind of treasure. In the past, many valued hako-iri-musume for its crystalline reputation, but recently this expression rather means an overly simple-minded “mama’s girl”. As for marital relations, there are two expressions in the Japanese language that seem to exert psychological pressure on single women. Takireiki (marital age) has an unpleasant connotation, as it is used to put pressure on a woman to get married. If she is past marriageable age and does not marry, she may be called urenokori, a word that usually means unsold, stale goods. These are very harsh, offensive expressions, and these days they are almost never used. But they are still alive in people’s minds, although today every Japanese woman has the right to decide for herself when and whom to marry.

A change in the consciousness of men and women, in their views on gender relations.

In modern Japan, the number of highly educated people is growing, and many moral criteria are being reassessed in their minds. Generally accepted views on the relationship between men and women are no longer so relevant these days; norms of sexual behavior and views on marriage have changed quite a lot. Sexual relationships between men and women in Japan have long been free, natural and healthy (Research Group for a Study of Woman's History, 1992, p. 106). But women's sex lives have been controlled by men since the Edo period, when the principles of Confucius justified the absolute power of men over women. In those days, a woman who entered into an intimate relationship with another man (not her own husband) was severely punished, although men were openly allowed to take concubines in order to have sons and maintain the ee system. Moreover, the government officially allowed the existence of brothels and other places where men met prostitutes. During the Meiji era, society was dominated by the belief that unmarried women should be virgins and young girls were brought up with great severity (ibid., p. 193).

Nowadays, under the influence of the media, the attitude of young people towards sex issues has changed greatly. Compared to previous generations, young people are more free to have boyfriends in their 14s and 20s, and premarital sex, pregnancy and even unmarried cohabitation are less criticized in today's Japan.

There are two types of marriages in Japan - arranged (o-miai) and “love marriages”. The difference between them is very important for understanding the Japanese attitude towards marriage. Arranged marriages were viewed more as a connection between different families (surnames, clans) than a personal relationship between a man and a woman. In the past, this is how most men and women who had never met before got married. Traditionally, representatives of both families themselves chose partners for future marriage. Today, the system of arranged marriages has undergone significant changes, but to this day it is one of the few chances for Japanese people to meet and get to know each other in fast-paced modern life. Often, an arranged meeting eventually leads to the creation of a good relationship, and it all ends in a successful marriage.

A 1994 study by the Ministry of Health and Welfare (Yuzawa, 1995, p. 83) showed that the frequency of “love marriages” was increasing. In 1990 there were five times more of them than contractual ones, although in 1950 there were three times more of the latter. This reflects a change in views on marriage and on what is considered more important in the final decision to get married (or to be married) - the wishes of parents or the own choice of young people.

Another trend in recent years is that an increasing number of Japanese people, as elsewhere in the world, are choosing to remain single; There are a growing number of single women pursuing their careers without the need for the financial security that was typically associated with a successful marriage. But it would be a mistake to conclude that few Japanese seek marriage. In fact, a 1994 General Affairs Agency survey (ibid., p. 95) showed that the majority of young Japanese are still committed to getting married someday.

Three reasons for the increase in the number of single people are considered. One of them is related to the group behavior characteristic of the Japanese way of life. People consider it important to adhere to group norms of behavior in order to maintain harmony with others. As a result, most Japanese have few opportunities to meet members of the other sex outside of work, and simply don't have time to make dates. Secondly, the existing social system is not suitable for women pursuing their own careers; they have little choice and are forced to remain unmarried. If a woman in Japan takes even a short maternity leave, it is very difficult for her to return to her previous job in the same position. The third reason is the large difference in views on marriage between men and women, but unlike most women, many single men view marriage as a social duty (Duty to Society), thus they can gain the trust of others, social responsibility and lower the expectations of their parents. Sociologist Kumata (1992, p. 118) notes that when turning to dating services, women predominantly identify the quality of a “good spouse” in men. At the same time, many Japanese men adhere to traditional views on women. Frankly, most of them view women as substitutes for their mothers: they need wives primarily to do housework, just as their mothers did. This approach leaves no room for women to be active in society, financially independent and to maintain a balance between work and family care.

Marital relations in Japan

The traditional Japanese way of life and thinking, whose origins lie in the Confucian morality of the Edo period, is still easily visible in family relationships. In Japan, it is generally accepted that the man plays the most important role in the family; husband and wife are far from equal team members. However, this does not mean that married women are merely subservient to men. In fact, they are assigned a significant role in managing the family, and women quite freely and effectively demonstrate their abilities in the field of raising children, running a household, drawing up a family budget, etc. In some Japanese families, husbands are exclusively engaged in financial support for relatives and friends, so how they do nothing to help around the house. There is even a special term for such husbands - sodai-gomi (“monumental/majestic trash”), since they only hang around the house after returning from work.

Once married, Japanese women often struggle with their social status, unlike their husbands, who must maintain social ties with colleagues or superiors to maintain group harmony. Playing an important role in maintaining the family economy as good wives and mothers (Reishauer, 1977, p. 232), many women today are beginning to take an active interest in the Internet and voluntary charity work, which gives them more opportunities to adapt in society.

If you look at the emotional side of communication between husband and wife, you will find that the Japanese rarely show excessive affection for each other, and they do not often talk to each other in public. Such marital relationships, as noted by Doi (1975, p. 132), can be explained by amae, or dependence, on which interpersonal relationships are based in Japan. Comparing Japanese marriage with marital relationships in the West, Doi emphasizes that the main difference between the relationships of spouses in Japan and in the West is whether marriages are consensual or not (arranged marriage or love marriage). Although this is acceptable for Japanese couples, people in Western culture usually confess their feelings with clear words and all behavior in a way that shows that they would never marry someone else in an arranged manner.

conclusions

Relations between men and women in Japan are going through a period of transition. The post-war Constitution gave men and women equal rights, which helped strengthen the position of women in society. Despite laws protecting equality, gender discrimination still leads to serious problems: sexual harassment, worse jobs, etc. This is partly due to the cultivation of Confucian thinking in society, which puts men first. Such social attitudes are reflected in both language and gender relations.

Recently, women have been receiving more and more serious education and playing an active role in society. This led to a number of new social phenomena: the average age of those getting married has increased, the birth rate has decreased, and the number of single people has increased. This is based on a change in the approach to relationships between men and women, which has led to a reassessment of views on marriage. However, traditional concepts such as "man on the outside, woman on the inside" are still alive in society and are supported by many in Japan. Therefore, whether a woman continues to work after marriage or not, all housework remains her responsibility. Men must earn money for their family by the sweat of their brow. All this is a remnant of the division of labor that dominates the IE system. If the changes that are taking place do not lead to devastating social consequences, the roles of men and women in society will become more proportionate, and more equitable relations between Japanese women and men will finally be established.

Bibliography

Reshauer E. The Japanese today: Change and contnuty. Tokyo: Bungey Shunju, 1977/1990.

Doi T. Amae zakko (Essence of amae). Tokyo: Kobundo, 1975.

Kumata V. Onna to otoko (Women and men). Tokyo: Horupu Shuppan, 1992.

Research Group for a Study of Woman`s History (ed) Nihon josei no rekishi: sei, ai, kazoku (History of the Japanese woman: sex, love, family). Tokyo: Kadokawa Sensho, 1992.

Yuzawa I. Kazoku mondai no genzai (Problems of the modern Japanese family). Tokyo: Nihon Hoso Shuppan Kyokai, 1995.

Marriage

Do you think Japanese people marry for love? Not at all. Despite the fact that the country is very developed in the field of digital technology, the rules of an almost primitive system still apply here. One of them is child matchmaking. That is, the parents themselves agree on marriage; we are not talking about love here. The one you walked down the aisle with is the one you will live with. And period. The parental decision takes precedence and is not challenged under any circumstances. Oddly enough, everyone lives happily ever after.

It’s good to wash often: myths about shampoo and hair care that only harm

"Dad is offended." Agata Muceniece about her relationship with Priluchny after the divorce

If there is little snow, there will be no harvest: December 16 is Ivan the Silent Day

No to kissing in public

How often have you seen couples kissing under the window of a house or in a park? Do you think their feelings are serious? Hardly? Then why this demonstration of feelings? For example, the Japanese believe that kissing in public is a huge shame. So nowhere in this country will you see couples kissing. On the other hand, this is not bad at all. The same lonely people do not feel inferior. And intimacy should remain intimate. You never know: what if the children see it? What can I say then? So the Japanese can also be understood.

Found a violation? Report content

Relationships between men and women in Japan

Relationships between a woman and a man in Japan are not built quite the same way as, for example, in Europe. Japanese family culture is based on Confucianism, in which the husband has great importance and greater weight than the woman.

Even at the linguistic level in Japan, there is a difference in the name of wife and husband. It is believed that the Japanese man lives outside the home, the woman in the house. Over the past years, relations between opposite sexes have undergone serious changes.

Since ancient times, men have performed many social functions in Japan. The Japanese man was involved in a large society - clans and professional groups, he occupied the best places in the hierarchy. A woman's place in ancient Japan belonged to the home. This does not mean that patriarchy was widespread in the country, as in China. For example, in many Japanese families, inherited property passed through the female line. If a man was in charge in a region, city or enterprise, then a woman was in charge in the house.

There has been a long division of influence between women and men in Japan. If she is the owner in the house, then he is the owner in the world. There was no talk of dividing responsibilities in everyone's sphere. The wife had no right to interfere in men's affairs, and he had no say in the distribution of finances. Moreover, it was not appropriate for a husband to do household chores - washing, cooking, cleaning.

Since ancient times, marriage in Japan has been divided into two types - love and contractual. The latter was concluded by relatives, and for love it was concluded only if the children completely refuse the proposal of their parents. Until the 1950s, there were more arranged marriages in Japan than love marriages.

Today, global emancipation has gradually affected Japan. Japanese women are actively involved in the country's social activities. Women were given the opportunity to achieve high positions in companies and work as they wish. In order to establish a career, a woman in Japan does not need to make much effort. Japan guarantees her social protection during pregnancy and childbirth. At the same time, maternity leave can harm a Japanese woman in every possible way; they will not be able to restore her to the same position after a long break. Having given birth to a baby, a Japanese woman will be forced to build her career from scratch, possibly even within the same company. Such social injustice gradually led to social loneliness of Japanese women.