This is the knowledge that most of us are given from childhood so that we can stay safe. And to do this, you need to understand what the colors on the traffic light dashboard mean. We know that red means “stop” and green means “you can go.” Simple enough, right? But what happens when you live in a country with a certain culture where the colors green and blue are defined by the same word?

Background

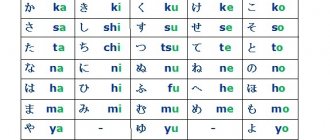

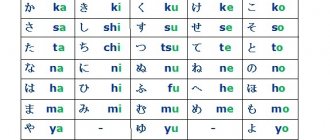

Many centuries ago, in Japanese, green had the same name as blue - “ao”. This linguistic feature has not gone away today, but even the Japanese themselves do not always understand why and how it arose. Some believe that this shade is associated with everything fresh and new, which is why even grass and unripe apples are called blue.

However, the green color has its own name - "midori", which is translated from Japanese as "escape" or "sprout". The new word appeared already in the 11th century, but many people, out of habit, continued to use the old name "ao". Because of this, at the time of the installation of the first traffic lights in Japan, the word “ao” was indicated in all official documents regulating their installation. Such confusion led to the fact that for several years in a row on the roads in the Land of the Rising Sun one could see colors that were unusual for a European person.

A little history

Hundreds of years ago, the Japanese language had only four primary colors: black, white, red and blue. If you wanted to call something green, you would use the word that meant blue (“ao”). And this system worked quite well until about the end of the first millennium, when the word midori (originally meaning "sprout") appeared, which was mainly used in writing to describe what we mean by the color green. Even then, midori was considered an "ao" shade. You can probably already imagine how difficult it was for the people of Japan to move from one meaning to another.

British strain of coronavirus recognized as more dangerous: latest research

“With creative abilities”: a psychic revealed the gender of Shnurov’s unborn child

WHO recommends vaccination against COVID-19 for mild cases

Compromise

5 years later, in 1973, the Japanese government came to the conclusion that the blue signal, unlike the green one, is much less visible from afar. This could cause dangerous situations on the roads, so the old lenses gradually began to be replaced with new ones. Thanks to this decision, Japan's roads became fully compliant with the Vienna Convention.

At the same time, the government did not want to radically change the type of traffic lights familiar to its citizens. Therefore, a compromise was found that allowed them to meet international standards without giving up the characteristics of their culture. To achieve this, road services began to use lenses whose shade was as close to blue as possible. Since then, even in official documents their color has become “midori”.

Japanese traffic lights on Russian streets: how to make life easier for motorists

New smart traffic lights have appeared in the northeast of Moscow. This Russian-Japanese project helped reduce rush hour travel times by 40 percent.

This is what a map of car fines looks like in real time. Purple and pink lights notify of violators. Tens, if not hundreds, of messages per second. Two thousand cameras on Moscow roads are triggered up to 50 million times a day, some of them become so-called chain letters. The average fine is 1000 rubles.

Cameras record up to three dozen types of violations, for example, running a red light. But maybe, thanks to smart traffic lights, drivers will begin to obey traffic rules? They know how to take into account traffic jams and switch red to green if the road is empty. A Japanese company installed five such traffic lights on Onezhskaya Street in the north of Moscow.

You can’t tell right away, but this is exactly what a smart traffic light looks like. It has a special sensor installed on it that regulates the flow density. The stronger the traffic jam, the longer the green light stays on. Two decades ago, a similar system saved Tokyo from congestion. In Moscow, too, there are already results - this street has become less congested by 40 percent.

And this is no longer just a traffic light, but a whole intelligent system. Sensors, video camera and controller. “Detectors do more than just record vehicles approaching and where they are going. They can also predict the flow of arriving vehicles. When cars approach the intersection, the detector counts how many have arrived and from which side. and made a decision on which direction to give priority,” explains Dmitry Gorshkov, deputy head of the State Public Institution Data Center.

Japanese experts have calculated that if all Moscow traffic lights are replaced with smart ones, it will be possible to save 10 million working hours – that’s six billion rubles a year. An important factor is the environment: exhaust emissions will be reduced. And such traffic lights will be installed not only in the capital. They will also be in the Leningrad region. In Voronezh we chose one of the largest streets - Moskovsky Prospekt. The road from the airport to the center. Ten traffic lights will be updated by the end of the year.

“The biggest congestion phenomena are observed in the city of Voronezh in the morning and evening hours. Modeling has shown that it is possible to achieve such results during morning and evening rush hours from 21 to 39 percent reduction in traffic at relatively low costs,” noted Vadim Kstenin, First Deputy Head of Voronezh for Urban Affairs.

It is not by chance that Japanese technologies appear on Russian roads. Last May, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe proposed a plan to Vladimir Putin to develop economic cooperation. One of the eight points is the development of urban infrastructure. And along with smart traffic lights, smart houses are coming to Russia, for example. And this is just the beginning of cooperation.

"Blue Signal"

Despite the fact that Japan replaced the lenses in all traffic lights more than 40 years ago, local residents still use the familiar expression “ao shingu”. It is difficult for Europeans to understand how the name of another can be used to refer to one color, but this is an integral part of Japanese culture. Therefore, even people born after 1973 still use the old expression without noticing anything unusual in it.

Now, having arrived in Japan, you will definitely not be surprised when you hear how locals call the traffic light signal with the strange phrase “ao shingu”, and not the logical “midori shingu”. Besides, you'll want to understand how the language confusion came about rather than trying to convince the Japanese that they're wrong.

- Author: emigrant

Rate this article:

- 5

- 4

- 3

- 2

- 1

(0 votes, average: 0 out of 5)

Share with your friends!

Colorful traditions

Extensive borrowing of vocabulary (gairaigo) from the English language also affected words denoting colors and shapes. Perhaps buru: (blue) and guri:n (green) will not replace ao and midori, although these words can be heard often now, but orenji (orange) seems to be used much more often than daidai, taking its name from another citrus fruit. Pink (pink) has also firmly entered the language, largely replacing momo (peach).

The Japanese color shu (cinnabar) is sometimes translated as "red" or "orange", while in Japan and other East Asian countries it plays a special role and has a special word for it. Typically, the torii gates of Shinto shrines are painted this color, boxes of Syuniku paint are worn along with personal seals of the Inkan, and ink of this color is used by calligraphy teachers when inscribing the work of students. Lacquerware often comes in this color.

Vermilion colored torii gate at Nezu Shrine in Tokyo

The color shu is probably the most visible to Westerners, but there are many other colors that are deeply rooted in tradition in Japan. Murasaki (purple) has long been the color of dress for the ruling class. During the Heian period (794-1192), the pale purple flowers of fuji (wisteria) were often celebrated, perhaps also due to associations with the powerful aristocratic house of Fujiwara (lit. "field of wisteria"). The writer Sei Shonagon, who lived at the turn of the 10th and 11th centuries, repeatedly admires these flowers. For example, in section “88. That which is magnificent" in her famous "Notes at the Head of the Head" she mentions "wisteria flowers of wonderful color, falling in long clusters from pine branches" (translated by V. Markova).

The special attitude of the Heian aristocracy to color is also manifested in the women's costume of the aristocrats, juni-hitoe, “twelve-layer robes,” worn by the ladies of the court. The number of layers in reality could be different and reach up to twenty. The colors of the garments were visible on the sleeves and hem, which were shortened at the top layers, and the creation of such ensembles was a form of art and demonstrated the taste of the wearer. There were complex rules that determined color combinations depending on the time of year, situation and status of the lady.

A modern analogue of such rules is the Shikisai Kentei exam, “Exam for (knowledge of) flowers.” The organization conducting it creates multiple-answer questions for designers and artists and thus defines standards. Some of the questions also relate to the exact determination of shades of colors traditional for Japanese culture, established by the Industrial Standards Committee of Japan.

Standardization, of course, simplifies life, but the beauty of a language lies also in its features. To speakers of other languages, a “blue” traffic light may seem strange, but such differences force us to look at the world from a new angle and allow us to see it from a broader perspective.

Some traditional Japanese colors

| beni (raspberry) | moegi (yellowish green) |

| momo (peach) | hanada (light blue) |

| syu (cinnabar) | ai (indigo) |

| daidai (orange) | Ruri (lapis lazuli) |

| yamabuki (kerria) | fuji (wisteria) |

| uguisu (warbler) | nezumi (mouse) |

Note: The table shows shades determined by the Japanese Industrial Standards Committee. Historically, these words could refer to different shades, especially those named after dyes, since the details of the fabric dyeing process greatly affect the color. They may also look different on different monitors.

Banner photo: “Blue” Aosingo traffic light against the backdrop of aoba, young leaves in early summer.

(Article in English published June 3, 2021)

About Japan

It turns out: In ancient times, the Japanese fished with the help of tamed cormorants. At night, fishermen lit torches in the boat, thereby attracting fish. Then a dozen cormorants, tied on long ropes, were released from each boat. Each bird's neck was intercepted by a flexible collar, which prevented the cormorants from swallowing the captured fish. The cormorants quickly filled their crops, and the fisherman pulled the birds into the boat, where he collected the catch. Each bird received its reward and was released for the next round of hunting for fish. The vandalism rate in Japan is one of the lowest in the world. In Japanese cities, there are vending machines on almost every corner where you can buy everyday goods. For Japanese, bowing is a common form of greeting. This could be a simple nod of the head, or a deep bow. The deeper and longer the bow, the higher the social status of the person being greeted. Fruits in Japan are terribly expensive. Here you can pay $2 for a single apple or peach. There is a common belief that the Japanese do not like to look their interlocutor in the eyes. The inhabitants of the Land of the Rising Sun themselves say that if a person looks away, it means he is hiding something. However, they avoid close gaze “eye to eye” (this is considered indecent and also means aggressive behavior). If Japanese parents scold a child and he stares into their eyes, they will say something like: “Well, why are you staring?” Because of this, Japanese children often stand with their eyes downcast at the moment of “moral reprimand.” In medieval Japan, looking into the eyes of a person with a higher social status was considered great impudence, and for such an act one could suffer greatly (even deprivation of life). Echoes of this have survived to this day and, apparently, this is why the Japanese subconsciously avoid making eye contact with their interlocutor. No one gives up space to older people on the metro, bus or train. If you try to do this, then you will not get rid of the “blessed” person. He will thank you. And then thank you again. And again and again... But there are special places for disabled people (there is a corresponding pictogram above them). A cup of coffee in Japan is very expensive. The cost of a cup of this drink in coffee shops exceeds 400 yen. And this is not at all explained by the fact that coffee is imported and subject to significant duties. The indicated fee is charged, rather, not for a cup of coffee, but for a place in a cafe. Having ordered a drink, a person can sit quietly in a cozy room for several hours, taking a break from the bustle of shops, wait out the rain, and read a book. No one will bother him, and the waiters will only pour cold water into his glass, always with a polite smile. Japanese banknotes feature very hairy men. The reason for this is not that in earlier times the Japanese had more facial hair. One of the most important tasks facing banknote designers is the desire to make them difficult to counterfeit. Therefore, the graphic image on the banknote should contain the maximum number of different small details - for example, a lush beard, mustache, wrinkles on the forehead. In Japan, drivers turn off their headlights when stopping at intersections. One of the foreigners once suggested that in this way Japanese drivers save battery energy. However, it is not. It's all about etiquette. When the car stops at an intersection, the driver does not need lighting, and by turning it off, he does not blind the eyes of oncoming traffic. I wonder why other countries don't do this? In Japan, the winner of the main sumo tournament receives a very unusual prize. He is presented with the keys to a new car, a year's supply of gasoline, a thousand shiitake mushrooms, one cow's worth of beef and a year's supply of Coca-Cola. During the fight, wrestlers are prohibited from grabbing each other by the hair, punching and kicking, kicking and punching each other in the head, chest and stomach, or poking each other in the eyes. Sumo does not allow for wimps, because one of the determining factors is the weight of the wrestler: almost all athletes weigh more than 100 kg (however, there are no weight categories in sumo, so the weight of two competing wrestlers can be different). The age of professional sumo wrestlers is from 18 to 35 years. At the same time, sumo champions enjoy almost universal love and respect. Two men - sumo wrestlers - meet in a ring (a circle with a diameter of 4.55 meters), the boundaries of which are lined with rice straw. They are dressed only in mawashi - a special loincloth. The wrestler's job is to push the opponent out of the ring (dohyo) or cause any part of the opponent's body (except the feet) to touch the ground outside the ring. These matches, on average, last only a few seconds, although some interesting matches can last for two or three minutes. At the same time, there are 82 basic techniques with sumo, and no one forbids participants to improvise. According to the Constitution, Japan does not have an army. But there are “Self-Defense Forces”, which are a small but well-armed, trained and combat-ready professional army. It mainly consists of the Navy and Air Force. This army is intended only for the defense of the country, and not for pursuing an aggressive military policy. Japan is a country with left-hand traffic, and the steering wheel of the car is on the right. The Japanese call a green traffic light blue. When the first street traffic lights appeared in Japan, the signals were red, yellow and blue. Then it turned out that a green beam is much more visible at a great distance than a blue beam. Therefore, the blue lenses of traffic lights were gradually replaced with green ones. But the custom of calling the signal allowing movement “blue” remains. The Japanese always take off their shoes before entering the house. This is done primarily to keep the tatami (mats) on which they sit while eating clean. You are not allowed to wear shoes (even slippers) on the tatami. Slippers are always removed when sitting on the tatami to eat. People wear special slippers in the toilet. They are standing at the door to the restroom. The Japanese eat food with chopsticks called hashi. The Japanese buy meat, fish and vegetables every day because they prefer fresh, unpreserved foods. That is why medium and small-sized refrigerators are in greatest demand in Japan. Rice is the main food here and is served with almost every meal. Miso soup is a favorite dish at any time of the day; it can be prepared for breakfast, lunch or dinner. The main ingredient of this dish is soybean paste dissolved in seaweed broth. Many women wear platform shoes with a height of 10-15 cm. Smoking in Japan is allowed almost everywhere except on local trains. Long-distance trains have special smoking areas. When washing, the Japanese do not sit in the bath to lather their bodies. . In ancient Japan, according to Buddhist laws, soap was strictly prohibited, since it was necessary to kill animals to make it. To somehow neutralize this prohibition, the Japanese washed themselves in very hot water. Now they lather up outside the bath and then rinse before plunging into the hot water to refresh and relax. When cooking, the Japanese use large quantities of fish, beef, pork, chicken and a variety of seafood. Most of their dishes add moderate amounts of spices and various soy sauces. When eating, the chopstick should never be inserted vertically into the food. In the past, food was offered to the dead in this way. Here it is customary to smack your lips while eating liquid food, such as soup. If you do not do this, it is assumed that you do not like the food, and the owner may even be offended. And finally, the Japanese are extremely polite people. If you need something, they will stop what they are doing and try to help. A surprise for sushi lovers (sorry if anyone was offended)