The Japanese language has many forms of expressing gratitude. However, not all of them are easy to understand and accept, because this is a different, Asian culture. Quite often, interesting words slip into English subs, the meaning of which is lost in the fog. To help you decipher such expressions, we have created a separate category on the terminy.info website. Therefore, do not forget to add us to your bookmarks, and everything will be in order for you. Today we’ll talk about an interesting term, it’s Itadakimas

, you can read the translation from Japanese below. However, before continuing, I would like to advise you to read a couple of other educational news items on the topic of anime slang. For example, what does Slash mean, how to understand the word Desu, what does Kokoro mean, what is Soulmate, etc.

So, let's continue, what does Itadakimas mean?

?

Itadakimas

is a word that almost every Japanese says before eating.

"Itadakimas" is an important phrase in your Japanese vocabulary. It is often translated as "I humbly accept", but in the context of eating it equates to " Let us eat"

", "Bon appetit" or "Thank you for the food." Some even compare it to the religious tradition of saying a prayer before eating.

But the use of itadakimasu

goes far beyond food intake. Although its roots go deep into history, saying “Itadakimas” before eating is believed to be a fairly recent Japanese custom. Get ready to dig deeper. You are going to study the history, usage, meaning and philosophy of the word itadakimasu.

Decoding, meaning

0 Itadakimas translation? The Japanese language has many forms of expressing gratitude. However, not all of them are easy to understand and accept, because this is a different, Asian culture. Quite often, interesting words slip into English subs, the meaning of which is lost in the fog. To help you decipher such expressions, we have created a separate category on the website fashionable-slova.rf. Therefore, do not forget to add us to your bookmarks, and everything will be in order for you. Today we’ll talk about an interesting term, Itadakimas

, you will read the translation from Japanese below.

However, before continuing, I would like to advise you to read a couple of other educational news items on the topic of anime slang. For example, what does Slash mean, how to understand the word Desu, what does Kokoro mean, what is Soulmate, etc. So, let's continue, what does Itadakimas mean

?

Meaning of Itadakimasu

In its simplest form Itadakimasu

used before obtaining something.

This is why the most common translation is itadakimasu: to receive;

get; accept; take (humble).

This explains why you say this word before you start eating. After all, you “get” the food, right?

Itadakimasu

(from the word itadaku) has Buddhist roots in Japan. This religion teaches respect for all living beings. This mindset extends to mealtimes in the form of gratitude to plants, animals, farmers, hunters, chefs and everything that goes into the food.

There are two characters for itadaku:

Saying Itadakimasa before eating is considered an essential part of Japanese etiquette, so it's important to learn how to do it correctly. Usually everyone will say this phrase together with everyone else, but it is also normal for each person to say it individually before eating.

Performing itadakimasu before eating is very simple, and has only four steps:

Here's a rule you should follow:

You can use

itadaku

when an actual physical thing is offered to you. It's like saying, "I'll take it," but politely.

When you are offered Gloves, video games, bed linen, cosmetics, a gasoline generator, you say this word. If you are offered a physical item, you can use itadaku to receive it.

What should you do if you are offered something non-physical, such as advice, a hug, a ride to the airport, or a trip to the park?

How to say thank you at the Japanese dinner table

Now let's move on and discuss how you can show your gratitude at the Japanese dinner table. Japanese phrases to express your appreciation are shockingly more than just "thank you."

These two expressions are “gochisou sama deshita” and “itadakimasu”.

You can say "Itadakimasu" at the beginning of the meal and "Gochisosama deshita" at the end.

If you haven't started lunch yet, say "Itadakimasu." The word "itadakimasu" can be translated as "I humbly accept it", but the intended meaning goes far beyond that.

“Itadakimasu” is a way to be grateful and remember the people who were the link between you and food for the Japanese.

This includes farmers, sellers, cooks, family, and so on. The diner also encourages the sacrifice of animals and vegetables that become food.

The phrase at the end of a Japanese meal is “Gochisosama deshita.” The literal meaning of this expression is “it was a feast” or “it was a delicious meal,” but the intended meaning is “thank you for the food.”

History of Itadakimasu

When you pick up your chopsticks, you should thank all nature and living beings, the Emperor and your parents. ー Walkthrough by Kuku Michibiki Gusa, 1812

G.

Buddhism

came to Japan during the Asuka period, bringing with it the "raising" of actions when receiving objects from people of high status, or when eating food or drink originally offered to the gods (osagari お下がり). So naturally, itadaku, a verb meaning to lift things above your head, began to be used as a humble form of words meaning "to receive", such as morau 貰う and choudai suru 頂戴する.

But only centuries later, in 1812, the use of itadakimasu

while eating, it began to take its current form. A book was published in Japan called Koukou Michibiki Gusa 孝行導. It was a guide to etiquette for everyday life, and it contains a sentence that historians point to as the origin of the modern meal of itadakimasu:

should thank all nature and living beings, the Emperor and your parents.

After this book was published, the idea of gratitude for food was spread by Buddhism through the Jōdo-shinshū sect. Although the monks did a good job popularizing the habit, not everyone in the country accepted the concept. In 1983, Japanese historian Isao Kumakura showed that " itadakimasu

" remained a regional practice until the early twentieth century. He surveyed people from all over Japan who were born during the Meiji and Taisho eras and asked them where their habits came from. According to the results, not all of them said "itadakimasu" before eating. So when did the mealtime phrase become a national custom?

According to Shoyo Yoshimura's book, it was strengthened during the early Showa era, when education was controlled by Imperial Japan. Teachers forced their students to thank all living beings, the emperor and their parents before eating. They will be grateful to " itadakimasu

" This promise was called shokuji-kun 食事訓, from 食事 meaning "food" and 訓 meaning "lesson" or "doctrine". This is very similar to the passage from the previously mentioned Kuku Michibiki Gusa.

Although itadakimasu's origins extend back to the Asuka period, its current form has only existed for about 75 years. This means that there are still people alive today who remember a time when Japan did not use " Itadakimasu"

" countrywide. And who knows what the next evolution of this custom will be?

Even nowadays, it is not customary in all parts of Japan to say thanks before eating with the word “Itadakimas”. According to research conducted by J-town:

There is a saying in Japan:

お米一粒一粒には,七人の神様が住んでいい. Seven gods live in one grain of rice.

This emphasizes the idea that every bite of food is very important.

the itadakimasu ritual

is gratitude and reflection, even if only for a moment. In this light, starting a meal with "itadakimasu" means you should eat the entire meal. Something gave its life for food, so it can be considered disrespectful to leave large pieces of food. The next time you see the last grain of rice on your plate, don't hesitate to spend time trying to pull it out.

After reading this article, you learned what Itadakimas means

translation from Japanese, and you won’t get into trouble again if you suddenly come across this funny word again.

Source

Itadakimasu! (Itadakimas!)

“Itadakimas” does not just mean a wish for a bon appetit. She expresses deep gratitude to everyone involved - most of all, our Mother Earth.

The literal translation of this phrase from Japanese means “I humbly accept it.” It is addressed to those who prepare food. That is, for farmers, fishermen, sellers, etc. And also for the one who prepared the food. Not to mention, it is a thank you to those who sacrificed themselves to become food itself - animals, plants and whatever else will soon end up in a person's stomach.

The difference here from religious gratitude is that with this phrase you thank not only God, who created all the food for us, but also everything that is on the dinner table.

The ancient Japanese art of food gratitude involves giving thanks to someone who died for you to give you food to live.

The phrase is said immediately at the table before eating. Some also clasp their hands together, sometimes holding chopsticks with their thumbs, with their eyes closed.

Learn to be grateful to the Earth, which produces crops, water, grains, trees, animals; and those people who work in the fields, deliver food to the shelves in stores, who cook your food.

How the concept of いただきます (itadakimasu) helps reduce food waste

As you get to know Japanese culture and the Japanese language, you will often come across the expression いただきます. Literally it is translated as “I humbly accept,” but when it is pronounced at the table, it rather means “let’s eat!” or “bon appetit!” However, some, translating this phrase literally, liken it to prayer before eating, an expression of gratitude to God for sending food.

Meanwhile, the expression いただきます is used not only at the table, it has many more areas of application than you might think. The expression いただきます has its roots in history, and saying it before eating is a relatively new custom in Japan. Get ready to dig deeper. You will learn the history, rules of use, meaning and philosophy behind the phrase いただきます

Gochisousama! (Gochisosama!)

Gochisousama is a phrase used after finishing a meal. Can be literally translated as "It was a lot of work (cooking)." Thus, it would be fair to interpret from Japanese as "Thank you for the food, it was a holiday." Again, appreciation goes out to everyone involved in the preparation of the meal.

This phrase is connected with the fact that in the old days the owner of the house had to work hard to get food for the table. Therefore, it was customary to value this work. And sincerely thank you for the treat. Therefore, "Gochisosama" is translated as "Thank you for the food."

In cafes and restaurants, this gratitude after a meal is expressed to everyone - cooks, waiters and even those workers who stand at the entrance to the establishment.

The meaning of the expression いただきます

People say いただきます before receiving something, and if you look in the dictionary, you will see that this verb is basically translated as “to receive”, “to accept”, “to take.” This explains why this phrase is said before eating. After all, you “get” the food. The verb いただきます (and its dictionary form 頂く(いただく, itadaku) have their roots in Buddhism, which teaches respect for all living things. This thinking extends to food, in the form of gratitude to plants, animals, farmers, hunters, cooks and everything that has been related to this food

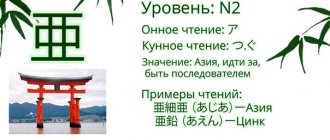

The verb いただく can be written in two ways:

Both spellings are correct, but the character 頂 is more common.

By the way, in our online school a lot of time is devoted to studying hieroglyphs. If you dream of understanding the Japanese writing system, welcome to join us!

A little history

Itadakimasu and Gochisousama are Japanese rules of etiquette. They come from the Buddhist past of the land of the rising sun.

The fact is that in Buddhism there are two prayers of gratitude - before eating and after. Before eating, they thank those who prepared the food or who are serving the meal, as well as the products themselves from which the food was prepared. After the meal, gratitude must be expressed to everyone who in one way or another participated in bringing this food to the table.

How to use the expression いただきます

Knowing the meaning of the expression いただきます is one thing, but it is also important to learn its correct pronunciation and remember the times when it is appropriate to use it.

いただきます correctly at the table

Saying いただきます before eating is an important part of Japanese etiquette, so you need to learn how to do it correctly. Usually everyone says this phrase at the same time, but if you say いただきます separately from each other, it will also be considered appropriate.

Pronouncing the phrase いただきます is accompanied by a number of simple actions:

When else to use the phrase

As we mentioned earlier, the verb いただく is most often translated as “receive”, “accept”. But these words do not fully reveal its meaning and, on the contrary, can confuse you. So there are times when it is better not to use the expression いただきます.

Here's the main rule:

You use the verb いただく when you are offered something material. The expression いただきます in this case will be translated something like this: “Thank you! I will take it."

Gloves, video games, wigs, spare basketball nets - whatever it is, when you receive an item, you can use the expression いただきます.

A:

A: Do you want this fish?

B: (soudesune. itadakimasu. arigatougozaimasu)

B: Yes, this one. I'll take it. Thank you.

Consider forms of politeness when using the verb いただく. Even though the verb いただく is a more polite form of the verb もらう(morau), if you use simple forms of the verb and do not translate the verb いただく into its polite form いただきます, it will not sound much more polite. So, the degree of politeness of the following statements will be approximately the same:

But when you form polite forms from these verbs, using the verb いただきます will be much more polite than using the verb もらいます.

If you want to surprise all your friends with your knowledge of forms of politeness, you can use the following very polite expressions:

Other uses of the verb いただく

What if you received something intangible from another person, such as advice, a hug, or a favor?

Don't use the expression いただきます when you receive something intangible. You can only use the expression いただきます when receiving intangible benefits in very specific cases.

For example, you would not use the verb いただきます after you have been given advice in the present tense, but you can use it in the past tense. You will also use this verb to ask for advice:

(Anata no adobaisu o itadakitaindesu) I need your advice.

アドバイスをいただけませんか?(Adobaisu o itadakemasenka?) Could you give me some advice?

The following phrase will sound strange and incorrect:

I take advice from Koichi's teacher.

The strange thing is that at the time the phrase was uttered, the advice had already been given and it would be more correct in this case to say:

Koichi's teacher gave me advice.

I decided to follow teacher Koichi's advice.

If you are being driven to the airport, station or anywhere, the same rule applies here. It is okay to use the verb いただく when asking for a ride, but it is incorrect to use it when receiving a ride.

家まで 乗せていただきたいんです。(いえまでのせていただきたいんです, ie made nosete itadakitain desu) Я хотел бы, чтобы вы отвезли меня домой.

hikouzyou made noteitadakemasen ka?) Could you give me a ride to the airport?

You can use the verb いただく when talking about a service received:

きのうはびえとさんにえきまでのせていただきました, kinou wa bietosan ni eki made noseteitadakimasita) Yesterday Viet drove me to the station.

If someone wants to hug you, do not spread your arms out to the sides in a greeting gesture and say 頂きます. It will look weird. Hugs are generally accepted between friends and family, so expressing politeness in a formal manner would not sound appropriate. The only time the verb いただく and hugs go together is if you've made a date with your boss and politely ask him to give you a hug.

Can you hug me?

Of course, this example looks rather unusual, but, theoretically, such a situation could arise. Although, it's probably against your company policy to go on a date with your boss. You don't want problems with the hiring manager, do you? Still, it would be better if you didn’t have to use this phrase.

One of the few intangible things you can accept when using the verb いただく is the opportunity you are given. But when someone asks you to say a toast at a wedding, for example, you can't just answer them with いただきます. You'll need to respond with something like, “I'd like to take advantage of the opportunity...” In other words, you'll need to be more specific about what you're going to do rather than just saying, “I'll take it on.” Here's how to say it in Japanese:

Home 。(す, kakunowa tokui dewaarimasenga, anohi watasi ni okita koto nitsuite kakaseteitadakimasu)I'm not very good at writing, but I would like to take the opportunity to talk about what happened today.

I gratefully accept the opportunity with sing now.

As you can see, there are many nuances in using the verb いただく. The more you study Japanese, the more you will understand how and why words are used the way they are in certain situations. You will have an intuitive understanding of the language. But now, at the very beginning, you need help in the form of such grammatical explanations.

Japanese language and anime.

wow...

LANGUAGE AND SPEECH OF THE JAPANESE

Needless to say, the vast majority of people in Japan are Japanese, and so naturally speak and write Japanese. Other languages, including, contrary to popular belief, English, are used to an extremely limited extent in Japan.

"Do you speak Japanese?"

To the ear, Japanese speech is very pleasant and musical: simple pronunciation, an abundance of vowels, including long ones, and the absence of sharp intonation changes - all this makes it look like a smooth murmuring stream of sounds. At first it seems that speaking Japanese is quite easy. However, a European who begins to study Japanese very soon becomes convinced that it is completely different from all other languages known to him.

First of all, as it turns out, this language contains almost nothing that is usually taught in foreign language classes at school. Of course, like other languages, Japanese has nouns, adjectives, and verbs. But they look exotic: nouns have no articles, no cases, no plural, no gender. Verbs have no gender, no person, no plural, no future tense, only past and non-past. Most adjectives closely resemble verbs, in particular, they have a past tense. They, like verbs, have no future.

But if these circumstances, albeit with a stretch, can be attributed to the advantages of the Japanese language from the point of view of a person starting to learn it, then in other respects, complete disadvantages await a beginner. First of all, this is, of course, writing.

Japanese letter

For writing, the Japanese use special characters - hieroglyphs, borrowed from China back in the 6th century. In Japanese they are called “Chinese characters” (kanji). It was in China that these pictures were “constructed” more than four thousand years ago, and they are still used to write not only in this country, but also in Japan and South Korea.

A hieroglyph is a sign of a fixed outline, to which a certain independent meaning and a certain reading are assigned. While maintaining a common or similar spelling of hieroglyphs, their readings in different languages may be different. So, seeing a separate sign of four lines, a Chinese will read it as “fan”, a Korean as “pom”, a Japanese as “inu”, but they will all associate it with the concept that is conveyed in Russian by the word “dog” .

How many characters are there in Japanese? Judging by large dictionaries, there are a frighteningly large number of them, from 40 to 50 thousand. However, in reality, only a small part of them is used in ordinary texts - a little more than 2000 characters. There is a list of “everyday characters” approved by the Japanese government, which contains 1945 characters. Ideally, this is exactly how many (and similar) signs a 15-year-old Japanese high school graduate should remember. In general, according to Japanese estimates, in order to understand the meaning of 95 percent of ordinary texts, you need to know 2,000 characters.

2000 characters - is it a lot or a little? Of course, compared to the alphabets of European languages, which contain two to three dozen letters, this is an impressive number. On the other hand, a person freely retains such a number of objects in his memory - anyone can check this by making a list of people whose names and surnames he remembers by heart. There will probably not be a thousand names in it.

It is known that in China several tens of thousands of characters are actively used for writing. How do the Japanese get by with two thousand? The fact is that, fighting the invasion of “Chinese signs,” the Japanese, by the 10th century, based on the simplified writing of a number of hieroglyphs, created their own kana syllabary alphabet, in which each character corresponds to one syllable. Nowadays there are even two such alphabets: one with smooth, rounded outlines of characters (hiragana), the other more “angular” (katakana). Unlike hieroglyphs, the signs of the syllabary alphabet by themselves do not carry any meaning; meaning appears only after they are arranged in sequences that correspond to the sound of Japanese words. Nowadays, as a rule, unchangeable parts of words are written in hieroglyphs, changeable parts are written in hiragana, and borrowings from European languages are written in katakana. However, many Japanese words are written only in alphabet.

The fact that there are two alphabets is not surprising. If you look closely, writing in Russian also has two systems of signs - uppercase and lowercase letters, the styles of which sometimes differ quite significantly. There are no capital letters in Japanese text; all characters - hieroglyphs, katakana and hiragana - are approximately the same size and flow in a continuous stream; spaces between words are not accepted. If you consider that the Japanese text is sometimes diluted with Arabic and Roman numerals, as well as foreign words written in Latin letters (by analogy with the “Chinese signs” of kanji, the Japanese call them “Roman characters” - romaji), then it is easy to imagine the horror evokes this cocktail in a person who has just begun to study the Japanese language.

But the difficulties don't end there. Very soon, a beginner learning Japanese will learn that in general any Japanese word can be written in syllabic characters. Why, one might ask, are hieroglyphs needed then? Isn’t it easier to write, if not in Latin letters, then at least with the signs of your own Japanese syllabary alphabet, which has become familiar over a thousand years? Will the Japanese soon give up hieroglyphs?

Unfortunately for students, the answer to this question is no. The Japanese, apparently, will never give up hieroglyphs. To do this means to break the entire structure of the native language that has been built over hundreds of years, that is, ultimately, to cease to be Japanese.

To understand why this is so, we need to look back to the distant history of the borrowing of hieroglyphs from China in the 6th century. At that time, China stood at a much higher level of cultural development than its neighbors on the Asian mainland. It was already an ancient country with an extensive system of government, with bureaucracy, and, of course, with its own hieroglyphic writing, “designed” two thousand years earlier specifically for the characteristics of the Chinese language.

The Japanese language in those ancient times did not have its own written language, and therefore Japanese words were initially written in Chinese characters, signs of a completely different language, with a different pronunciation and grammar. The simplest of the difficulties that arise can be easily understood by anyone who tries to write down the Russian word “yet” in English transcription.

In addition, the Japanese did not perceive Chinese words well and distorted them in accordance with the norms of their pronunciation. So, for example, the Chinese reading of the character for “dog” (“fan”) in Japanese lips turned into “ken”. What also greatly “ruined life” for the Japanese was the fact that, along with the new writing, the Chinese gave them a lot of new concepts that simply did not exist in the Japanese language before. For example, along with the hieroglyph “dog,” the term “fanju” (Japanese “kenju”), which means “cynicism,” entered the language. Therefore, very soon the literate (half-Chinese) Japanese were faced with the question: how, after all, should the hieroglyph denoting the concept of “dog” be read? If in Japanese it is “inu”, then Chinese borrowings will be pronounced incorrectly. If in Chinese (“ken”), then you will have to forget the purely Japanese word.

The solution was found to be flexible in Japanese. Gradually, it was tacitly agreed that each “Chinese sign” could have more than one reading: in native words it is read in Japanese, and in Chinese borrowings it is read in Chinese, or, more precisely, in the way the Japanese hear Chinese pronunciation. Now most characters have the so-called “Chinese” reading (on-yomi) and the “Japanese” reading (kun-yomi). The general rules now are as follows: if the hieroglyphs are in a group, then they are read in Chinese readings, if individually, surrounded by the alphabet, then in Japanese. However, there are more than enough exceptions to these rules.

The situation “one sign - several readings” also exists in other languages, but rather as an exotic phenomenon rather than as an integral feature. Let’s say, if in some place in a Russian text there is a sign “3”, then in principle it can be read as “ze” or “three” - it all depends on the signs standing next to it.

In Japanese, this is not the exception, but the rule. Many characters have several Chinese readings because they were borrowed at different times and from different regions of China, where the pronunciations differ.

This is how a writing system, unique in world practice, has developed, which causes numbness and prostration in all those beginning to study the Japanese language: not only is the solid Japanese text replete with numerous “furry” icons, but they are read differently depending on what is standing around one sign or another.

It is impossible to abandon hieroglyphs for this reason: when borrowing, the Japanese lost Chinese intonation, and as a result, a lot of words were formed in Japanese that sound the same, but are written in different hieroglyphs. For example, if you open a Japanese phonetic dictionary, you will find about a dozen words borrowed from Chinese that are read “kosho”. Their meanings are very different, depending on what hieroglyphs are used. There are words here that mean “light”, “negotiations”, “official announcement”, “minister of education”, etc. Chinese people can distinguish such words by ear because they are pronounced with different intonations in Chinese. The Japanese distinguish them only when they are written down, and written down in hieroglyphs. If you write these words down in alphabet or just read them out loud, then without context it will be completely unclear to the Japanese what kind of “kosho” we are talking about.

From this it is clear that in the foreseeable future the Japanese language will not be able to do without hieroglyphs. Of course, even now a large number of identically sounding words creates a lot of problems for the Japanese. Almost any article from a Russian or, say, English newspaper can be read on the radio and listeners for whom these languages are native will understand what is being said. The Japanese State Broadcasting Corporation has a special service that “translates” newspaper articles into spoken language, selecting synonyms and eliminating similar-sounding words from the text that listeners may misunderstand.

“It never happens that there are no problems”

But, as the advertisements say, “that’s not all.” The difficulties of hieroglyphs completely pale in comparison to the peculiarities of the use of language by the Japanese themselves in speech and writing.

First of all, it should be noted that the Japanese language is characterized by a special structure of utterances, the center of which is always the interlocutor. Let's give a simple example: if you ask a question containing a negation like “Is this not your briefcase?”, then the usual answer in Russian will be “No, not mine.” Approximately the same statement will be constructed in English, German, and Spanish. The Japanese will certainly answer: “Yes, not mine.” The point here is the special attitude of the Japanese towards his interlocutor. If the European’s answer concentrates on himself and implies something like “No, not mine (this is a briefcase, and everything else does not concern me),” then the Japanese answer is built around the questioner and confirms that he is right. And if we are talking about confirmation, then, of course, from the Japanese point of view, you need to say “yes”: “Yes, (you are absolutely right), this is not my (portfolio).” In other words, in a Japanese answer, everything is subordinated to the task of maximizing the response to the interlocutor’s question, the task of providing maximum attention, and showing courtesy to the partner.

Hence the extraordinary number of polite words and forms of politeness in the Japanese language; This is why the Japanese in speech (and especially in writing) constantly elevates his interlocutor and belittles himself. About the interlocutor it is said: Your honorable name (sommei), Your fragrant name (gohomei), Your precious letter (gyokuon), Your honorable wife (reifujin). They say about themselves: my inept work (sessaku), my stupid sister (gumai), my pitiful home (settaku), although in reality for the Japanese everything may not be as hopeless as he says.

It is estimated that over the course of its centuries-old history, the Japanese language has created about 50 forms of address in the respectful-official, high, neutral, reduced, friendly polite, modest, familiar styles, about 50 forms of greetings, 40 forms of farewell, 20 forms of apologies, etc. Remembering them all and applying them correctly depending on the situation is an extremely difficult task, in order to cope with it you need to be Japanese.

Japanese grammar allows you to construct your speech literally by looking at the expression on the interlocutor’s face, monitoring his reaction, because the rules are such that the final word, most often the predicate, gives a positive or negative meaning to a statement. When you listen to a Japanese speaker, you first learn “who”, “what”, “when”, “where”, “why”, and at the very end - “did” or “didn’t do”. So in Japanese it is quite possible to construct statements in such a way as to begin with health and end with peace: not only formally and grammatically, but also in the essence of the language, this will be completely correct.

The Japanese make extensive use of these features of their native language. A real historical case is usually cited as a classic example of this approach. The military ruler of Japan, the eighth shogun of the Tokugawa house, Tokugawa Yoshimune (1684-1751), once condemning at a military council the actions of the rulers of one of the regions, during his lengthy statement he suddenly noticed from the faces of other military leaders that this condemnation would not be accepted by them , and, therefore, will complicate the situation. And Yoshimune managed at the last moment to change the meaning of the entire statement to the exact opposite, for which he only needed to change the form of the last word: “arumai” (“is not”) to “aro” (“probably is”).

The deliberate vagueness of statements is also associated with a special attitude towards the interlocutor. It is considered impolite to clearly formulate your point of view, because this means imposing it on your interlocutor. The interlocutor’s opinion may be different, and therefore the harsh wording will be unpleasant to him. Having the habit of expressing themselves unclearly, acquired with their mother’s milk, the Japanese, at least on a subconscious level, expect this from others, and therefore are amazed at the “unaesthetic” and rudeness of the direct statements of Europeans, especially those of them who consider “cutting” to be a sign of valor. “the truth” and tell your interlocutor to his face everything he thinks. From the Japanese point of view, this manner of expression looks boorish and arrogant.

In order to emphasize the non-categorical nature of statements, the Japanese often use chains of negations. You can, of course, say: “There are problems” (mondai ga aru), but a Japanese would most likely say: “It’s not possible that there are no problems” (mondai wa nai koto wa nai). It seems too simple and straightforward for a Japanese to say, “I agree,” and he says, using four negatives in a row, “It is not that it is not that I do not disagree” (fusansei de nai to iu koto de mo naku wa nai).

Polite refusal

In general, communication with the Japanese is fraught with many mysteries for a foreigner, who soon becomes convinced that the Japanese are very reserved in expressing their opinions and desires, and the statements of the inhabitants of the land of the rising sun are often very far from their direct meaning. Such “gaps” can be so large that they raise suspicions of hypocrisy among foreigners. In particular, it is absolutely impossible to get an explicit refusal from a Japanese person. Instead, figures of silence, unexpected transfers of conversation to another topic, vague statements and similar means are abundantly used.

But even the “positive” statements of the Japanese often cannot be deciphered. So, for example, an invitation like “Come visit me sometime” most likely simply means “I think you’re a good person.” The phrase “Let's have a drink together the next time we meet” means “I wouldn't mind having a drink with you if I ever meet.” Finally, if a Japanese person says, “I'll think carefully about everything you told me and will let you know one way or another,” what he really means is, “You should consider a more suitable invitation,” that's a polite refusal in Japanese. .

When all this reaches the consciousness of a foreigner, he becomes completely bewildered, not understanding how one can even talk, much less achieve mutual understanding, with the Japanese. However, the salvation is that the Japanese behave this way only with a stranger, and as the acquaintance continues, if the guest managed to win them over, they become more and more friendly and benevolent. Another thing is that this is a very, very slow process.

"English"

Many researchers note that when communicating with the Japanese, it is extremely desirable to know at least the basics of the Japanese language and be able to pronounce at least a few commonly used phrases. The Japanese sees this as respect for him and his country, which will certainly endear him to the guest. If learning Japanese is a matter of the future, then most often you have to communicate in English. Almost all Japanese study English to some degree in school, but, as a rule, have little speaking practice and have difficulty communicating. Therefore, when trying to communicate with a Japanese in English, it is better to speak slowly and clearly, and if there was no understanding, then sometimes it is useful to write what you want to say: this way the foreigner will perhaps be understood faster. For all that, as Japanese researchers themselves note, the Japanese take great pleasure in showing that they are able to communicate with a foreigner in his native language (and they most often consider English to be such) and they speak without being embarrassed by their pronunciation and mistakes and are happy when they are understood.

“... yes there is a hint in it”

As already mentioned, in a conversation the Japanese constantly belittles himself and “raises” his interlocutor. When communicating with an unfamiliar foreigner, this feature is expressed even more clearly. Therefore, there is no need, for example, to blindly take on faith the words of a Japanese person that his salary is small, his house is inferior, his wife is ugly, his children are hog-eaters, etc. The guest will be unpleasantly surprised when he is greeted by a beautiful Japanese woman on the threshold of a mansion owned by a “poor man,” and the children, as it turns out, are studying at one of the best universities in the country. It is also hardly worth puffing up from the consciousness of one’s own exclusivity when the Japanese note that a guest speaks excellent Japanese or learned to eat with chopsticks remarkably well during his two days in the country. This is nothing more than a tribute to politeness, as the Japanese understand it.

It’s probably best to approach all this with a proper dose of humor, which the Japanese also appreciate, although here it should be noted that Japanese humor is very different from ours. Therefore, trying to tell our jokes to the Japanese is an almost useless exercise. They have a completely different system of values and realities, so our hints are incomprehensible to them.

And a European will not see a hint where it is in the speech of a Japanese, and which other Japanese will easily understand. The exquisite praise of a neighbor's daughter, who began to study music, the words that such a talented girl will undoubtedly achieve a lot as a pianist in the future, is in fact a complaint, understandable to every Japanese, that all the neighbors have no peace from her playing.

To illustrate the Japanese’s penchant for allegory, our famous Japanese scholar Professor S.V. Neverov cites the story of an American student who interned in Japan and lived in the house of her Japanese friend. Both girls were fond of Japanese theater and regularly attended performances of traditional Kabuki theater, and then heatedly discussed what they saw. With Japanese houses closely packed and sliding doors open wide in the summer, the emotional speech of the American woman carried very far and disturbed the peace of the neighbors. One of the neighbors, having finally decided to express general complaints, once turned to the American woman, saying: “It’s so good that you have such a friend, one can only envy how willingly you talk until late, exchanging impressions that you have accumulated.” All this was said with a smile, in the most benevolent tone. The American, taking this as a high assessment of their friendship, began to sincerely praise her friend. It became clear to the neighbor that her words did not reach their goal. I had to talk again, in approximately the same words, this time with a Japanese friend. When the true meaning of this conversation was explained to the American woman, she was stunned, saying only: “I’ve been studying Japan and the Japanese language for so many years, but how difficult it is to understand the soul of a Japanese person!”

History of the expression いただきます

Before you pick up chopsticks and start eating, you should thank nature and all living things, the emperor and your parents

ーexcerpt from a book on the rules of etiquette by Koko Michibiku Gusa, published in 1812

The character 頂(いただ) means “top of the mountain.” Initially, the meaning of the verb いただく was “to put something on the head” - so allegorically the head was likened to the top of a mountain. It wasn't long before the word became associated with receiving things, especially food.

But only centuries later, in 1812, the expression いただきます began to be pronounced at the table, as they do now. A book was published in Japan called Koko Michibiki Gusa (孝行導草, こうこうみちびきぐさ, Koukou Michibiki Gusa). It was a guide to etiquette in everyday life, and in it, among other rules, there was one that prescribed how to behave at the table. This publication may be considered the first officially documented use of this expression in the form in which it is familiar to us:

箸 取らば、 天地 御代の 御恵み、 主君や 親の 御恩あぢわる。 (はしとらばあめつちみよのHashi toraba ametsuchi miyo no onmegumi, syukun ya oya no goon ajiwaru) Before you pick up chopsticks and start eating, you should thank nature and all living things, the emperor and your parents.

After the publication of this book, the idea of expressing gratitude to all living things before eating was spread by the Jodo Shinshu school of Buddhism. And although the monks did a great job spreading this custom, not every Japanese learned about it. Research by historian Isao Kumakura in 1983 showed that until the early 20th century, saying いただきます at the table was a regional, that is, not universal, practice. He interviewed people throughout Japan born during the Meiji and Taisho eras about their childhood habits. According to this survey, not all of them said いただきます when they sat down to eat. So when did this phrase become a custom at the state level?

According to Shoyo Yoshimura's book, this custom began to take root at the beginning of the Showa era, and primarily through the educational authorities of the state. Teachers forced students to thank all living things, the emperor and their parents before starting to eat. They had to end their thanks with the phrase いただきます. This rule was called 食事訓 (しょくじくん, syokujikun), where 食事(しょくじ, syokuji) meant “food” and 訓(くん, kun) “study.” This is very similar to the quote from Koko Michibiku Gusa that we mentioned earlier.

Thus, even though the custom of saying いただきます before eating dates back to the Asakusa period, it has only been widespread in its current form for about 75 years. And this, in turn, means that there are still people alive who remember Japan without this custom. Who knows what subsequent changes this ritual will undergo in the next 100 years?

Our days

Although these phrases are still very popular in Japanese culture, "Itadakimasu" and "Gochisosama" are gradually disappearing among the Japanese. The reason may be people who no longer see the need for it when everything happens so easily. Food is available in such quantity and variety that we don't have to worry about where we get everything from. But what is important is not physical presence at the table or the correct reading of these Japanese phrases. The main thing is a feeling of gratitude that we should all remember!

Put your hands together! (Or don't fold!)

Although the custom of saying いただきます before eating has taken root in Japan, it is performed differently in different parts of the country. Here's what we learned about Japanese table etiquette from a study conducted by J-town:

Undoubtedly, differences in people's behavior largely depend on the customs accepted in the region of the country where they live. Remember when we said that the custom of saying いただきます before eating was originally spread by members of the Jodo Shinshu school of Buddhism? Followers of Jodo Shinshu taught to place the palms together and make a slight bow when pronouncing the phrase いただきます. Hiroshima is known for its high concentration of Jodo-shinshu temples, so many of them that the followers of Buddhism from Western Hiroshima even have a special name 安芸門徒 (あきもんと, akimonto).

In the study, 92% of respondents from Hiroshima said they put their palms together when saying いただきます (note the red color of Hiroshima on the map). In fact, the entire western part of Japan is marked in red on the map, apparently, the educational work of the monks from Jodo Shinshu had a lasting effect and influences people's behavior to this day.

Japanese appetite, or itadakimasu. Part 1: BENTO

Share:

Among those who have managed to travel around Asia, there is a fair belief that the people in those parts love to eat. Some people admire the healthy appetite of Asians, some find it disgusting, and some are perplexed: how can you eat so much and still be so skinny? Scientists and nutritionists around the world are asking this question, conducting various studies, while we, people of the post-Soviet space, literally and metaphorically hungry for delicious food and restaurant culture, have been experiencing a gastronomic boom for more than 20 years now. devouring dishes from cuisines of different nations of the world with an appetite that would be the envy of many Asians, including.

Despite the fact that dumplings, now considered the national dish of Russian cuisine, came to us from China, our people do not have a particular love for Chinese food. But, for reasons unknown to me, we became attached to Japanese cuisine with all our hearts, and the opening here and there of “drying”, “yakitorechnye”, and simply the presence of rolls in every eatery at one time corrected the statistics for the city of Moscow, where Japanese restaurants popularity came in second place.

I always thought that Japanese cuisine was one of my favorites, but only after moving to Tokyo did I realize how insignificant and ridiculous my knowledge was! Imagine that you meet a foreigner who tells you: “I adore Russian cuisine!”, and you ask him: “What do you like from Russian food?”, and he says: “Pancakes!” You smile and, waiting for the continuation, say: “...Eeeee?..” And he begins, as in the movie “Girls,” to rattle off a monologue, but not about potatoes, but about pancakes: “I love pancakes with caviar, with condensed milk, with meat, with cottage cheese...” Or you meet an “expert” who will also tell you about Pozharskaya cutlet and – at the very level of “God” – about jelly! So I, with my knowledge of rolls, nigiri, yakitori and chukka salad, are not far was from the fictional character described above.

Meanwhile, food for the Japanese is the holy of holies! Their truly excessive, bordering on lustful, love for food became an amazing discovery for me. I didn’t think that this is a country where the cult of gastronomy is just off the charts. Jokes aside, a third of the pages in magazines like GQ and Vogue are devoted to food! Not recipes, but where to eat ready-made food and, of course, in your own country. And here it is important to note that even a person who cannot read Japanese understands that this is not all just for the sake of filling his belly. This is gourmandity, savoring, a hidden part of the Japanese character . This is the only (think about it - the only!) manifestation of the Japanese ability to enjoy life. These people don’t know how to celebrate noisily, dress up in all the best for corporate events, go headlong into festivities for several days in a row, throw spontaneous parties, keep restaurants open until the last customer, party in après-ski bars at ski resorts... But what about eating? - on an ordinary or special day - the Japanese can do this like no other!

Whatever they say, Japan is indeed not quite Asia, and if it is appropriate to draw parallels in this case, then in terms of food, the Japanese are Asian French, because such a combination of diversity, sophistication, uniqueness, coupled with centuries-old traditions in all of Asia simply does not exist.

A number of the following publications will be devoted specifically to food in Japan: what a particular region is famous for, what food traditions date back to the Middle Ages and are observed to this day, where the most delicious sushi is, how not to offend the Japanese at the table, and so on. Part one is a kind of hors d'oeuvre or amuse bouche.

BENTO AS A SIGN OF SOCIAL STATUS

My guide to the world of gastronomy in Tokyo was Murakami-san. No, not Haruki the writer, but simply a namesake and also my subordinate, and the most truly Japanese Japanese, one of those who did not grow up or was born abroad, but came to Tokyo many years ago from his native northeastern Sendai , famous for its horse meat sashimi. For Murakami-san, the Japanese concept of “omote-nashi” (hospitality) was sacred, and therefore it is not surprising that the unlucky Russian manager, who proudly declared on the very first day that she likes sushi, had to be bailed out so that from only raw fish, she did not suffer from volvulus or protein poisoning.

The first lesson was lunch break.

Every day at 12 noon, life in central Tokyo is completely transformed for half an hour. At any time of the year and in any weather, waves of people dressed in black and white rush out into the streets in a noisy stream from the skyscrapers of business centers. These people disperse in friendly formation to numerous restaurants around their offices, humbly stand in line, quickly eat and return to their seats. The most amazing thing is that even if you have lunch outside the office, you still fit it in 35-40 minutes maximum! Such a phenomenon as a canteen is rare for a Tokyo business center, but the presence of many restaurants inside office premises is considered the norm. Instead of a cafeteria, these restaurants serve business lunches and also prepare bento, a standard-sized portioned lunch that contains the food served at the restaurant. Each restaurant places tables in the corridor in front of the entrance, places bento on them, and if you are in a hurry and prefer to eat directly at your workplace, then you pay for the lunchbox and return to your place.

In general, bento itself is an amazing phenomenon. The amazing fact is that the contents of these lunchboxes, the ingredients themselves, together make up the ideal proportion of proteins, fats and carbohydrates necessary for a rich and at the same time healthy lunch. Any lunchbox certainly includes rice - the basis of all basics, Asian bread - vegetables (a must!) and animal protein. On average, the component is as “according to GOST”, that is, about 20% protein, 30% fat and 50% carbohydrates. The Japanese car does not fail here either.

One day I asked my colleague and part-time second guide to the world of Japanese gastronomy, Hiroshi-san: what was it like before? Has there always been such a cult of food? And how did people eat during the difficult post-war times for Japan - did bento disappear?

Hiroshi-san surprised me (and, I admit, upset me a little): people in Japan have always loved food. He said that initially bento was collected only for children at school, and much later they began to make such lunches for everyone. During the war, as well as after it, bento boxes were collected for children, trying to maintain the proportions as much as possible. But, of course, not everyone succeeded. And a “poor” bento was considered to be one that contained more rice than meat (which sometimes was not present at all). This is Japanese class inequality: there is always food, and status is determined by what you eat...

Are you hungry already? Then, as the Japanese say, itadakimasu - that is, “Bon appetit”!