In 1935 German architect Bruno Taut made a long trip to Japan. In this amazing country for three whole years he searched for inspiration and climbed into the most remote and incredible corners. Bruno soon wrote a book about what he experienced and saw, which forever changed the life of one small village...

Luggage storage Gassho Observation Myozenji Museum Where to eat Wada House When to go How to get there By car Useful information

Hidden deep in the mountains, Shirakawa-go warmly greeted the great architect. He was so amazed by its landscapes and originality that he could not help but share his delight with the world. And today more than one and a half million people come to this village every year. Why could she be so interested?

What is Gassho

Small, neat and very picturesque... Huts with huge thatched roofs stood on both sides of the road, standing out impressively against the backdrop of the blue mountains. And it is for them that millions of curious travelers come here.

Situated in the valley of the Sho River and the Chobu mountain ranges, the settlements of Shirakawa-go and Gokayama have long been isolated from the bustling centers. The main craft of the local residents was silkworming. They set up workshops in the multi-story attics of their houses, under a massive thatched triangular roof, which, moreover, protected them from heavy snowfalls in winter. From the outside, such a house resembles hands folded in prayer, which is why in Japanese it is called “Gassho-zukuri”. And this is a very special and unique style for Japan.

ENJOY YOUR HOLIDAY: Shirakawa-go, Gifu

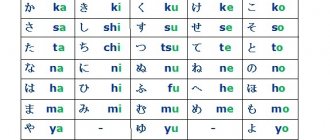

The UNESCO World Heritage Site number 734 is the Japanese villages of Shirakawa-go (transliteration from Japanese, as well as phonetic features of Japanese, English and Russian languages allow alternating sounds [s] and [sh], thus the second possible variant of the name of the village is Shirakawa-go), located in Gifu Prefecture, and Gokayama (Toyama Prefecture)

The settlements received such a high status thanks to social interaction, which made it possible to preserve the cultural and historical heritage expressed in the architectural craft. The traditional way of life and human cohesion have remained unchanged for centuries, and today it delights and surprises at the same time.

The tallest and most recognizable Japanese houses

Gassho-zukuri (合掌造り) , the tallest and most recognizable structures in Japan, require special care to function properly. In particular, this concerns the renovation of thatched roofs - all village residents participate in this matter, helping each other, in fact, jointly maintaining the integrity of the external appearance. The word gassho in Japanese means a prayer gesture where the palms are pressed together. You can also draw an analogy with the expression “I’m in the house,” familiar from childhood. The literal translation of “gassho-zukuri” sounds like “holding hands in prayer” - here, even at the linguistic level, the human cohesion inherent in the very concept is visible.

The functionality of the high, steep gable roof was to protect the house from heavy snowfalls characteristic of mountainous areas. The angle of the slope made it possible to quickly clear it of snow in winter, and during the rainy season the water did not stagnate on the surface of the shelter - but rolled down. In addition, the base of the thatched roof, which was a lattice of logs, beams and twigs, made it very strong to withstand the thick layer of snow that looks so fabulous in winter photographs.

Traditional Japanese houses are usually called “minka” (民家) . They exist in various versions, being determined not only by geography, but also by the lifestyle of people. Gassho-zukuri is equated to a special school of architecture, because houses were built from accessible and cheap materials, such as wood, bamboo, clay and straw. In a minka with a high roof there is no chimney - the internal heating was provided by a hearth, the fire in which had to be constantly maintained. The premises on the first floor were usually residential, and there was no division into rooms - screens played the role of walls, while silkworm workshops were located on the second floor.

Today, gassho-zukuri houses have become more modern inside, but this does not change the essence - villagers still work together when it is necessary to re-thatch the roof or help with snow removal. This way of life has not changed for 300-400 years - this is exactly the age of the houses in Gokayama and Shirakawa-go. Human unity, loyalty to traditions and the desire to preserve the historical appearance of the settlement (after all, many buildings and structures are truly authentic) have turned peasant villages in the mountains of Japan into a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Doburoku

Late September - early October is the time for the Doburoku festival in Shirakawa-go. The autumn holiday coincides with the harvest season and has been celebrated for more than 1,300 years. The event program includes not only a festive procession, but also folk songs and traditional dances, which can be watched in temples.

People turn to the gods, asking for peace for the village, prosperity and security for their home, and a bountiful harvest. The drink that bears the same name as the festival, Doburoku sake, is offered as an offering to the gods. This “country wine” is also known as Nigori unfiltered sake (濁り酒 - Nigorizake ). It is most often referred to as “cloud sake” due to the characteristic white cloudy hue that results from fermentation.

Initially, doburoku was common among peasant families, but over time it became one of the traditional directions in the production of sake (even despite the ban imposed during the Meiji era [0], 1868-1912). The drink has a mild sweetish taste, perfectly complements spicy dishes and can even be a dessert wine.

In 2010, sake breweries in Akita Prefecture introduced a “dark” version of Nigori by adding powdered charcoal to the sake.

Probably, the name of both the festival and the drink are interconnected, since they are closely intertwined in the historical and cultural aspect, including agriculture and peasant life, the traditions and customs of which are still carefully preserved. In Shirakawa-go you can visit the festival museum - the exhibition tells not only about the event itself, but also demonstrates how the rituals and ceremonies characteristic of the holiday have survived to this day.

Observation room

There are several dozen Gassho houses preserved in Ogimachi, many of which are about 300 years old! I really wanted to see the whole village, so first of all we went up to the observation deck.

From above, the houses and streets look like toys. And from here you can clearly see the architectural features that Bruno Taut admired so much. All houses thoughtfully face one direction so that there is enough light and air inside, and the snow from the roof melts faster.

By the way, if you don’t want to walk 20 minutes to the observation desk, a shuttle runs from the stop at Wada House (3 minutes from the bus station) to the Observation desk. Pay cash 200 Yen (≈ 1.8 USD) on the bus. Departs every 20 minutes from 9 am to 3:40 pm.

There are restaurants and toilets upstairs. Speaking of food and other joys of tourists... Almost all of Gassho have long been sold to investors for hotels, cafes and souvenir shops. But there are several museums that we hurried to check out before lunch.

Myozenji Museum

The houses are very similar inside and there is no point in going into all of them. I would even say that Myozenji alone would be enough, because... This is the largest and most interesting structure of Shirakawa-go.

Cost - cash 300 Yen (≈ 2.7 USD). Opening hours: 8:30 ~ 17:00 (Apr-Nov), 9:00 ~ 16:00 (Dec-Mar)

For about 200 years, it has housed a local shrine - the Myozenji Temple, and in the second part - “kuri” - monks lived. This five-story Gassho was built in three years from Japanese cedar and without a single nail! A hundred to two hundred workers covered the huge thatched roof at the same time. The straw needs to be changed every 30-50 years, one day at a time. The Japanese call such a flash mob "Yui"

Inside, the atmosphere is even more unusual. The lower living room, in the best traditions, is covered with tatami. In the corner there is a large fireplace - it’s also a kitchen, it’s also a heating system, it’s also a disinfectant. The fire in the house was maintained around the clock, the smoke rose to the upper floors and properly smoked the wood, destroying insects. Over the course of two hundred years, the wood darkened and began to shine like varnish.

We were incredibly lucky to get to the museum at a time when the owners had just added firewood and the acrid, stinking smoke filled everything around. Therefore, the attics had to be inspected at an accelerated pace, so as not to suffocate.

As I already wrote, the main occupation of the inhabitants of the Shirakawa and Gokayama region was raising silkworms. They did this right at home - in the attics. Such personal mini cocoon factories. Today, all that remains of the silkworms are tools. There are a lot of them located in Myozenji, and if it weren’t for the smoke, we would have spent a lot of time studying and looking at them.

Having limited ourselves to walking through all the floors and the views from the window, we went down to the temple part. It’s interesting, but there was no smell of fire here at all and there was silence. The walls of the temple were painted by the famous Japanese artist Hamada Taisuke. It was so beautiful and cozy that I didn’t want to leave.

Village of Shirakawa-go. Japan

Five hundred kilometers northwest of Tokyo, in the gorge of the Japanese Alps, there is a village of 59 houses. The place Shirakawa-Go is not marked on any map. Just recently, a rare rickshaw driver decided to travel into this wilderness, and these places were impassable for horses. So the inhabitants of the village of Shirakawa-Go lived in complete isolation from the whole world. And thanks to this isolation, they created their own architectural style, unlike anyone else.

Gashezokuri means “hands folded in prayer.” It is the hands of Buddhist monks that resemble the roofs of houses in the village of Shirakawa-Go. The houses themselves were made without a single nail. Heavy beams are held together with hemp rope and flexible walnut rods, and the walls are fitted to each other according to the principle of a children's construction set. I must say that these houses are very stable. They can withstand any bad weather and hurricanes. Under the pressure of a strong wind, the roof can move, but thanks to the walnut rods it immediately returns to its place. Some of these houses are over 400 years old and people still live in them.

The guards of Shirakawa-Go trace their ancestry to the famous Taira clan, a subsidiary branch of the imperial family. In the 12th century, the Taira family entered into a power struggle with another clan. A confrontation began, in comparison with which the Wars of the Red and White Roses of England pale in comparison. As a result, the Taira were defeated and fled. They found refuge in the impenetrable Shchegava valley. A huge Taira family settled under one roof. Since then, large, sometimes two- or three-story houses have been built here, which can comfortably accommodate up to 30 people.

In Shirakawa-Go, Lenin's dreams of a bright future under communism came true. The population of the village has lived as a commune since ancient times and still lives today. They also all work together. If the time has come to replace the roof, and this needs to be done every 50 years, then the whole village gets involved. If today you come to your neighbor for help, you must repay him in kind when the time comes. In Japanese it is called "yu". Previously, when the village was isolated from the outside world, such a system was simply necessary. Today, young people are trying to shirk their responsibilities.

From the 17th century and for 250 years, the main occupation of the inhabitants of Shirakawa-Go was the production of gunpowder and raising silkworms on the roofs. After the Meddi revolution, gunpowder was banned. Several cold winters exhausted the entire silkworm. The tree became a source of income for the villagers. Today, Shirakawa-Go relies on tourism. Foreigners are attracted by the outlandish architecture and age of the village, while the Japanese come here to see real winter.

From December to March, up to 4 meters of snow falls here. Shchegawa Valley is one of the few places in Japan where there is spring, summer, autumn and winter.

However, 30 years ago there might not have been a trace left of the ancient buildings of Shirakawa-Go. Under the influence of time and harsh climate, houses began to collapse. They wanted to build a modern settlement on the site of the village. The division of the land began. And then a group of activists came up with slogans: “don’t sell,” “don’t give,” “don’t destroy.”

No one knows what saved the ancient village, but it was preserved, and with it the pristine beauty of the valley, which the head of the Taira clan liked so much when he was looking for a place to settle.

source https://www.vokrugsveta.ru/tv/vs/cast/175/

272

Where to eat

There were a couple of hours left before the bus to Takayama. From the Myozenji Museum we walked to the other side of the river across the bridge and came back for lunch.

On the other side of the Sho River there is an open-air museum - Minkaen. Entrance to this village of 26 houses costs 600 Yen (≈ 5.5 USD)

There are cafes in Shirakawa-go at every turn, but many have queues, low ratings and insane prices. If you don’t want to wait a long time and pay dearly, Shiraogi is quite suitable.

A complete list of cafes and restaurants in Ogimachi can be found here.

LiveInternetLiveInternet

Shirakawa-go village and gassho-zukuri house museum. The names of the houses come from the steep thatched roofs that look like hands folded in prayer (gassho). In 1976, Shirakawa-go was declared a protected architectural area of Japan, and in 1995 it was recognized as a world heritage site under the protection of UNESCO as “an outstanding example of a traditional way of life, perfectly adapted to the environment and local social and economic conditions.”

The historic villages of Gokayama (Toyama Prefecture) and Shirakawa-go (Gifu Prefecture) are located in a remote mountainous region of Honshu Island, which was cut off from the rest of Japan for long periods of time during the winter.

These are not exactly villages in our understanding. It is like a district that includes other subdistricts. Accordingly, on the territory of such a village there may be settlements with their own name (so to speak, “sub-villages”), or there may simply be individual houses along the road.

Most often, when tourists say that they have visited Shirakawa-go, they mean the “sub-village” of Ogimachi, which has the highest concentration of what people come here for - houses in the gassho-zukuri style.Snowy winters (up to 4 meters from December to March) and rainy summers place special demands on architecture: a steep roof must withstand heavy snowfalls and be resistant to moisture. The slope of the gassho roof is about 60° (usually no more than 45°).

Local houses were built without a single nail. All beams are fastened with hemp rope and walnut rods. But despite this, the houses here are very stable. They can handle any bad weather. Some of the huts that people still live in are over 100 years old.

The main occupation of the local residents was silkworm breeding, so the upper floors of the dwellings are skillfully adapted for the needs of silkworming. These dwellings are unique; you will not find anything similar in Japan.

It is not known when such houses began to be built. It is not even really known when people entered this region. The first chronicle mentions date back to the 12th century. Only in the XIII century. Buddhism penetrated here.

Residents of the village of Shirakawa-Go trace their ancestry to the Taira clan, which is a subsidiary branch of the imperial family. The population lives in a kind of commune: they work together, repair their homes together, and help each other in everyday affairs. The main occupation of local residents for 250 years has been raising silkworms and producing gunpowder. But tourism has now become the main source of income.

The feudal wars of the Sengoku period, however, did not bypass Shirakawa. In the 15th century in Ogimachi they even built a samurai castle; in its place there is now an observation deck. In the 17th century The territory was taken over by the Tokugawa shogunate.

At this time, a certain economic boom began in the region, associated with the start of silkworm breeding. Before this, almost the only source of income was timber, which is still abundant here: 98% of the territory is covered with forest. Because of this, by the way, there is almost nowhere to grow rice here; there is barely enough for food. Local carpenters were highly valued and were hired from different places to build first samurai castles, then palaces and offices for the shogun and his entourage.

At the end of the 19th century. the authorities finally paved a road from south to north, which went straight along Ogimachi. The way of life began to change, many began to build ordinary houses covered with tiles along the highway.

After World War II, economic growth began, people began to unanimously demolish gassho-zukuri, which were not very comfortable for living and difficult to maintain. Moreover, the massive construction of dams on the Syo River flowing here has begun. The government became puzzled by the preservation of gassho-zukuri, and they began to be evacuated from areas designated for flooding to Ogimachi. With the first nine such houses, the Gassho-zukuri Minka-en open-air museum began in 1972.

tyts

Ogimachi is not the only gassho-zukuri village. About 15-20 km north of here is the historical region of Gokayama. Historical - because it does not exist on the modern administrative map of Japan, just like Shirakawa-go. These are now the villages of Taira, Kamitaira and Toga in Toyama Prefecture. The villages are located halfway between Tokyo and Kyoto. They are a UNESCO world cultural heritage.

Wada House

Finally, we decided to go to one more house - the Wada family. Their ancestors had a high social status and the interior was much more expensive than that of the monks. But in general, the essence is the same: a residential ground floor with tatami and a fireplace, a large wooden attic with tools and steep views of the village.

Entrance costs 300 Yen (≈ 2.7 USD). Opening Hours 9:00 ~ 17:00

Many of Gasse's houses in the village are rented out for the night and you can immerse yourself in history to the fullest. The only thing is that already half a year before our trip to Japan, all the old houses in Shirakawa were occupied. Find the full list of invitees here.

And we looked at the wonderful huts of silkworms, inhaled traditional smoke and wandered through the spring mud of the most popular village in Japan to a bus stop with hundreds of the same researchers.

But here’s what’s interesting... Despite the crowds of people and tourist polish, Shirakawa-go impressed with its coziness. And to feel its extraordinary atmosphere and uniqueness, you don’t have to be a great architect. So I recommend it from the bottom of my heart!

Kawagoe

40 km. from Tokyo is the city of Kawagoe, located in Saitama Prefecture, considered an uninteresting place. Although it’s definitely worth visiting the fortified city of Kawagoe (translation: “City of River Crossing”). All attractions in Kawagoe are located very compactly, 1 km away. from the city railway station. This area of the city is called "Little Edo" and can be walked around in a few hours. True, if you look into the many shops of local artisans and linger while tasting the delicacies of local cuisine, the whole day will pass unnoticed. Of course, the most interesting time to visit Kawagoe is the third weekend of October, when the traditional Kawagoe Festival takes place here - one of the most joyful holidays in the Tokyo region, when hundreds of merrymakers dressed in ancient clothes carry about 25 decorated stretchers (dashi).

Kawagoe owes its prosperity to its strategic location on the Singashi-gawa River and the Kawagoe-kaido Highway, the ancient route to the capital. All goods in Edo (today's Tokyo) passed through Kawagoe, and local merchants made fortunes by building the fireproof kurazukuri - black, two-story warehouse stores that are today the city's main attraction. At one time there were more than two hundred kurazukuri here, but their clay walls were not as fire-resistant as the builders had expected. And yet, about thirty such buildings have survived to this day, sixteen of the best of them are grouped along Chuyu-dori, a kilometer from the station.

Attractions Kawagoe

The ruins of Kawagoe Castle are now located in the city park. The residence of the daimyo Honmaru-goten . It now houses a museum with an exhibition of archaeological finds, although in fact the main interest is the building itself, built in 1848: a Chinese-style roof with pediments and spacious rooms with tatami mats and colorful screens.

Moving along Chuyu-dori, you can get to the small Shinto shrine Kumano Jinja , next to it there is a tall building where the sacred dashi stretchers are kept, which are taken out only during the annual matsuri. Not far from the temple there is an okashi sweet shop - Kameya, a warehouse and factory. These buildings now house the Yamazaki Art Museum , exhibiting works by Meiji period artist Gaho Hashimoto. Some of his elegantly painted screens are hung in the central gallery. Samples of the sweets that were once made here are displayed in a kura (warehouse) converted into an exhibition hall. Upon entering, all museum visitors are required to receive a cup of tea and okashi.

As you walk up Chuyu-dori, among the local artisan shops, check out Machikan, a shop selling swords and daggers, or Sobiki Atelier, selling beautiful items made from wood.

Next is the Buddhist temple Chokiin , on its territory there is a statue of an emaciated Buddha, and there is a lovely pond with lilies and sculptures of trees and plants.

On the main road, in the premises of an old tobacco wholesaler's warehouse, one of the first Kurazukuri, rebuilt after the great fire of 1893, is the Kurazukuri Shiryokan . In the living area, you can go down a tiny staircase from the top floor to the first floor. One kura displays early 20th-century firefighter uniforms and woodcuts of the fires that destroyed Kawagoe. The new Kawagoe Festival Museum is located very close by. There are two beautiful dashis on display, various exhibits related to this festival, and videos of past festivals.

Don't miss the Toki no Kane . It was restored in 1894, the tower was used as a fire tower to raise the alarm when smoke or fire appeared. The bell is now driven by an electric motor and rings four times a day.

Behind the bell tower there is another temple with well-groomed grounds - Yojuin Kassia Yokocho sweet alley - a picturesque pedestrian street where colorfully decorated sweets and toy shops are still preserved.

Kita-

in Half a kilometer from Kurazukuri lies Kita-in - the main temple complex of the Tendai Buddhist sect - another of the attractions of Kawagoe. The temple has existed in these lands since 830 and became famous when the first shogun of the Tokugawa clan, Ieyasu, declared Tenkai Sojo the "living Buddha" as the temple's abbot. So great was the veneration of the monks who lived there at that time that when the temple burned down in 1638, the third shogun Iemitsu donated one of the palaces of Edo Castle (on the site of the current Imperial Palace in Tokyo) for this temple. The palace was dismantled and transported to Kawagoe in parts. Today it is the only surviving building from Edo Castle.

According to legend, Iemitsu was born in a room with a painted ceiling. The palace is surrounded by a quiet park, a wooden bridge leads to the inner chambers of the temple, decorated with sparkling gilded candelabra. Here you can also see Gohyaku Rakan , an amazing forest of stone statues. Although the name translates as "500 rakan", there are actually 540 mysterious small statues of Buddha's followers. None of them are alike. Kitai has its own little Toshogu. Like its famous counterpart at Nikko, it commemorates the spirit of Tokugawa Ieyasu and is decorated with vibrant colors and intricate carvings.

When to go

Shirakawa-go is open all year round. According to statistics from the official website, the most popular months are May, August, September and October.

- Snowfall - from December to February

- Cherry blossoms begin from mid-April to mid-May

- Red maples - October-November

- The annual Doburoku Rice Festival takes place in mid-October.

- The village hosts the Light Up festival for several days in early January and February. All snow houses are beautifully illuminated. At this time there are especially many people interested, so the number of tourists is limited by registration. You can check the dates and sign up for 2021 using this link

Find the full program of events for the year here

Login to the site

Five hundred kilometers northwest of Tokyo (Gifu Prefecture, Chubu Region, Honshu, Japan) in the gorge of the Japanese Alps there is a village of 59 houses. The place Shirakawa-Go is not marked on any map. Just recently, a rare rickshaw driver decided to travel into this wilderness, and these places were impassable for horses. So the inhabitants of the village of Shirakawa-Go lived in complete isolation from the whole world. And thanks to this isolation, they created their own architectural style, unlike anyone else. Gassedzukuri means "hands folded in prayer." It is the hands of Buddhist monks that resemble the roofs of houses in the village of Shirakawa-Go. The houses themselves were made without a single nail. Heavy beams are held together with hemp rope and flexible walnut rods, and the walls are fitted to each other according to the principle of a children's construction set. I must say that these houses are very stable. They can withstand any bad weather and hurricanes. Under the pressure of a strong wind, the roof can move, but thanks to the walnut rods it immediately returns to its place. Some of these houses are over 400 years old and people still live in them.

The guards of Shirakawa-Go trace their ancestry to the famous Taira clan, a subsidiary branch of the imperial family. In the 12th century, the Taira family entered into a power struggle with another clan. A confrontation began, in comparison with which the Wars of the Red and White Roses of England pale in comparison. As a result, the Taira were defeated and fled. They found refuge in the impenetrable Segawa Valley. A huge Taira family settled under one roof. Since then, large, sometimes two- or three-story houses have been built here, which can comfortably accommodate up to 30 people.

In Shirakawa-Go, Lenin's dreams of a bright future under communism came true. The population of the village has lived as a commune since ancient times and still lives today. They also all work together. If the time has come to replace the roof, and this needs to be done every 50 years, then the whole village gets involved. If today you come to your neighbor for help, you must repay him in kind when the time comes. In Japanese it is called "yu". Previously, when the village was isolated from the outside world, such a system was simply necessary, but today young people are trying to shirk their responsibilities. From the 17th century and for 250 years, the main occupation of the inhabitants of Shirakawa-Go was the production of gunpowder and raising silkworms on the roofs. After the Meddi revolution, gunpowder was banned. Several cold winters exhausted the entire silkworm. The tree became a source of income for the villagers. Today, Shirakawa-Go relies on tourism. Foreigners are attracted by the outlandish architecture and age of the village, while the Japanese come here to see real winter. From December to March, up to 4 meters of snow falls here. The Segawa Valley is one of the few places in Japan where there is spring, summer, autumn and winter.

However, 30 years ago there might not have been a trace left of the ancient buildings of Shirakawa-Go. Under the influence of time and harsh climate, houses began to collapse. They wanted to build a modern settlement on the site of the village. The division of the land began. And then a group of activists came up with slogans: “don’t sell,” “don’t give,” “don’t destroy.” No one knows what saved the ancient village, but it was preserved, and with it the pristine beauty of the valley, which the head of the Taira clan liked so much when he was looking for a place where he could settle.

Here is a general plan of the village

And here's a little more detail

Good to know

- Smoking is prohibited in the village, because... all buildings are very flammable

- You are not allowed to film with a drone in Shirakawa-go without special permission. More details here

- Refrain from going anywhere, many yards and houses are private property

- Near the bus station there is a currency exchange office and an ATM, which is important because... Almost all museums and souvenir shops only accept cash

- There are no trash cans on site

- There is free “SHIRAKAWA-Go Free Wi-Fi” in different parts of Ogimachi

- Onsens are hot thermal water baths. Shirakawa-go no Yu and Oshirakawa Onsen Shiramizunoyu are open to the public

What to buy and try in Shirakawa-go (Ogimachi)

- Doburoku sake. This is a local unfiltered sake that is so popular that there is even a whole festival dedicated to it in Shirakawa-go.

- Local pickled vegetables.

- Hoba miso is a local variety of miso paste.

- Kobo-cha tea. Once upon a time, back in the 9th century, the famous monk Kobo Daishi visited these places. He brought some tea leaves with him, gave them to the locals and told them to drink tea from them, as these leaves are good for the body.

- Hida beef is the most tender marbled beef from the region where Shirakawa-go is located.

- Gohei-mochi. A local product found in the mountains of Gifu and Toyama prefectures. The rice balls for this mochi are flattened before being threaded onto a grill stick. The mochi is then dipped in a sweet and salty sauce and grilled over a fire.

- Tofu. There are several small private enterprises in Shirakawa-go that make different types of tofu bean curd from local raw materials.

- Buckwheat noodles and dishes made from it. In Shirakawa-go, as in many other mountainous regions of Japan, buckwheat is grown, from which buckwheat noodles are made. The most popular dishes with it are zaru-soba, chilled buckwheat noodles, or kake-soba, which is served in a warm broth with vegetable tempura on top.

- Sarubobo talisman that attracts good luck. This is a rag doll, usually red in color, and should be shaped like a baby monkey. Other colors are also used, which may have a certain meaning.

How to get there

From Kanazawa

From Kanazawa to Shirakawa you can take Nohi Bus and Hokutetsu Bus. Nohi mainly go as far as Takayama, but make a stop in Shirakawa-go. Tickets must be purchased in advance, at the Hokutetsu office or online.

| Schedule | 8:10 8:40 9:10 9:40 11:10 12:40 13:10 13:40 14:40 16:00 |

| Buy online | Here |

| Travel time | ≈ 1 hour 15 minutes |

| Price | 2000 Yen (≈ 18.5 USD) |

Hokutetsu office near Kanazawa Station - marked on the map. Open from 6:15 to 20:00. There is also a bus stop to Shirakawa.

From Takayama

Most often people get to Shirakawa-go from Takayama, so Nohi Bus and Hokutetsu Bus run frequently. For some of them you can buy a ticket and reserve a seat online - marked in the table below as “(R)”

Holders of the “Takayama-Hokuriku Area Tourist Pass” and “SHORYUDO Bus Pass” cannot use them to make online bookings. You can order by phone +81-577-32-1688 or choose a flight without early check-in

| Schedule | 7:50(R) 8:20(R) 8:50 9:50 10:50 11:20(R) 11:50 11:20(R) 11:50 12:20(R) 12:50(R) ) 13:50 14:30(R) 14:50 15:50(R) 16:30(R) 17:50 19:00 |

| Buy online | Here |

| Travel time | ≈ 50 minutes |

| Price | 2600 Yen (≈ 24 USD) |

From Tokyo

There is no direct public transport from Tokyo to Shirakawa. Therefore, the route looks like this: take the Hokuriku Shinkansen from Tokyo to Toyama Station, and then take a bus to Shirakawa.

| Schedule | Shinkansen: check here Bus: 8:50 10:35 12:00 17:30 |

| Buy online | Bus: follow the link |

| Travel time | ≈ 4 hours |

| Price | ≈14,690 Yen (≈ 134 USD); 12960 (Shinkansen) + 1730 (Bus) |

From Kyoto (Osaka)

To get to Shirakawa-go on your own from Kyoto or Osaka, the fastest way is to take the Thunderbird Express (included in the JR pass) to Kanazawa, and then take a bus. In this case, I recommend staying a day or two in Kanazawa.

Another option is shinkansen + express through Nagoya to Takayama, and then by bus. Set aside 3-3.5 hours to see Takayama.

| Schedule | Thunderbird, Shinkansen and Express: check here Bus from Kanazawa: above Bus from Takayama: above |

| Travel time | ≈ 4 – 4.5 hours |

| Price | ≈8,490 Yen (via Kanazawa) – 11,950 Yen (via Takayama) (≈ 78 USD -109 USD) |