Now that we are familiar with both existence and verbs, we can use verb clauses to construct more complex sentences. As we already know, a complete sentence must end with either a real verb or a denotation of existence. This sentence can also be used as part of a more complex sentence.

Also remember that the polite form only comes at the end of a complete sentence, and the verb clauses within it must be in the normal form.

Connecting two sentences with “but”

You probably remember that we have already used 「でも」 to mean “but” or “however”. 「でも」 is always used at the beginning of a sentence, but there are two other conjunctions with the meaning “but” that are used to join two clauses into one complex sentence. These conjunctions are 「けど」 and 「が」. 「けど」 is conversational, while 「が」 is a little more formal and polite. (Note that 「が」 here is not the same identifying particle that we learned in the last chapter.)

Example

- 今日 【きょう】 - today

- 【いそが・しい】 - busy

- 明日 【あした】 - tomorrow

- 暇【ひま】 (adj.) - free (antonym of the word “busy”)

- 今日は暇。Today (I am) busy, but tomorrow (I am) free.

- I'm busy today, but tomorrow I'm free.

Note

: If the first part of a compound sentence ends in a noun or na-adjective without any cases and you do not use 「です」, you must add 「だ」.

Example

- Today (I am) free, but tomorrow (I am) busy.

- 今日は暇だけど、明日は忙しい。

- 今日は暇ですけど、明日は忙しいです。

- 今日は暇だが、明日は忙しい。

- 今日は暇ですが、明日は忙しいです。

If the noun or na-adjective has already been converted (for example, into a negative form with 「じゃない」), you do not need to add 「だ」.

- Today (I) am not free, but tomorrow (I) am free.

- 今日は暇じゃないけど、明日は暇。

- 今日は暇じゃないが、明日は暇。

A は B です。 Learn to write your first sentences in Japanese!

Japanese for beginners

AはBです

To compose simple sentences we need the following diagram:

A は B です。 (A wa B desu.) – A is B

Where A is the subject, B is the predicate

You can also write it like this:

Subject は Predicate です 。 (Subject wa Predicate desu.)

A must be a noun and B must be a noun or adjective!

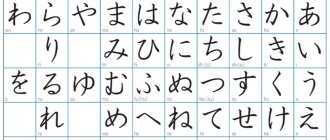

Those who have already learned hiragana may have a question: “Why is the hiragana syllable は(ha) read as wa here? Probably a typo..” But no) The fact is that when the hiragana syllable は(ha) acts as a definition of the topic of a sentence, it is read as wa

かのじょ(kanojo) – she; young woman

わたし は ユリャ です。 (watashi wa yurya desu) - I am Julia.

The topic of the sentence here is “I” (in Japanese it would be わたし) so after it comes the particle は(wa)

Literally translated: “I am Yulia”

かのじょはゆきです。(kanojo wa yuki desu) – She is Yuki

Literally, this sentence is translated as “She is Yuki” or “She is Yuki” (Sounds strange, doesn’t it? And who eats whom?!)

これはテレビです。(kore wa terebi desu) – This is a TV

Okay, what is this です。 (desu) and why is it even needed?

Desu is precisely translated as “is” or “to be”

The fact is that desu is used in formal and polite speech. And if a character uses です at the end and masu form of the verb, then he speaks in an official polite style.

In conversational style, です becomes だ(da)

In honorific speech: でございます(de gozaimasu)

By the way, with the help of this diagram we can say about our profession or the fact that someone is a student!

かしゅ(kashu) – singer, singer

かれはせいとです。 (kare wa seito desu) He is a student

かれ は せんせい です。 (kare wa sensei desu) - He is a teacher.

あなたはばかです。(anata wa baka desu) - You are a fool. (A fool is of course not a profession, but with the help of this scheme this can be said)

The second lesson of the section called “ Japanese for Beginners ” “Be sure to practice making sentences! You can give your examples in the comments! Good luck in learning Japanese and see you soon!

Source

Not long ago I received a request to create a series of posts about Japanese offers. It would be more correct to say that the request concerned very, very, very long sentences. And, although here it is necessary to turn to more professional literature, the proposal was nevertheless accepted and framed in the form of one’s own thoughts on this topic.

Another point: before the post about really long sentences in Japanese comes out, it was decided to create posts that will be used as links in the final publication. So to speak, “a run through Japanese proposals, a gallop through Europe.” All posts will be published in chronological order. There is a lot of work ahead, so please do not rush if the publication of a certain post is delayed.

Connecting two sentences with "therefore"

Two sentences are joined using 「から」 or 「ので」 to show cause and effect, but it is important to remember that the cause comes first. Therefore, it will be easier to remember their meaning as “therefore” rather than “because” to maintain order. 「ので」 is a little more polite and formal compared to 「から」.

Example

- ここ - here

- うるさい - noisy

- It's noisy here, so (I) don't really like it.

- It's noisy here, so (I) don't really like it.

Note

: Again, if the first part of a compound sentence ends in a noun or na-adjective without anything else (such as 「です」 or 「じゃない」), you must add 「だ」 to 「から」 and 「な」 to 「ので」.

Example

- ここ - here

- 静か【しず・か】 - quiet

- It's quiet here, so (I) like it.

- ここは静かだから、好き。

- ここは静かですから、好きです。

- ここは静かなので、好き。

- ここは静かですので、好きです。

Again, this only applies to nouns and na-adjectives that are not converted to another form.

- It's not quiet here, so (I) don't really like it.

- 好きじゃない。

- 好きじゃない。

っпяз. Basic Japanese grammar. 15. Word order

In this lesson I will continue to talk about complex sentences in Japanese. If you missed the previous lesson on this topic, it is available at this link.

Dictionary

- 私【わたし】 – I

- 公園 【こう・えん】 – park (free)

- お弁当 【お・べん・とう】 – lunch in a box (obento)

- 食べる 【た・べる】 (ru-verb) – eat, eat

- 学生 【がく・せい】 – student

- 行く【い・く】 (u-verb) – go

- 可愛い【か・わい・い】 – cute

Now that we've looked at how subordinate clauses are constructed and used in Japanese, it's worth looking at the correct word order.

And the word order in Japanese is very simple. If we consider the basic word order in Russian, then we will get something like [subject] [verb] [object] (I deliberately do not use words such as “subject”, “predicate”, etc.). In Japanese, everything is much simpler and the word order in the most basic sentence will be simply [verb]. For the simplest and most grammatically correct sentence, this is enough. If we want to add a subject, object, etc. to a verb, then they all must be located before the verb and be formed by the correct particles. However, their order is not important from a grammatical point of view. Only the emphasis of the sentence changes. All sentences below are correct in terms of grammar and complete in terms of meaning. And where something is unclear, it is understood that it should be clear from the context.

Grammatically correct sentences

So you don’t have to worry about word order in Japanese. Just remember the following rules.

Joining two sentences using “despite”

In a similar way, two sentences are joined using 「のに」, meaning “despite this” or “despite this”. As with 「ので」, add 「な」 if the first sentence ends with a simple noun or adjective.

Example

- 先生 【せん・せい】 - teacher

- とても - very

- 若い【わか・い】 (and adj.) - young

- 今年 【こ・とし】 - this year

- 不景気 【ふ・けい・き】 - (economic) recession

- クリスマス - Christmas

- お客さん 【お・きゃく・さん】 - buyer; client

- 少ない【すく・ない】 (and adj.) - small, meager

- かわいい (and adj.) - attractive; charming

- 真面目 【ま・じ・め】 (adj.) - serious; diligent

- 男【おとこ】 - man

- 友達【とも・だち】 - friend

Show/hide translation

- Tanaka-san is a teacher, but despite this, (she) is very young.

- There is a recession this year, so despite Christmas there are few buyers.

- Alice is beautiful, but despite this, because (she is) serious, (she) has few guy friends.

Word order in a Japanese sentence

Many Russian students starting to learn Japanese are faced with the difficulty of word order in Japanese - after all, it is so different from word order in Russian (although in fact there is no hard and fast rule in Russian - we can alternate words in any order due to the case system ).

But, you must admit, it is unusual to put the verb at the end of the sentence, and prepositions as postpositions (that is, after the word to which they relate). Maybe some of you will remember Master Yoda's speech from the Star Wars saga? But it was the structure of the Japanese language that the creators of the character took as a basis to give the phrases of the great Jedi a special flavor. But you shouldn’t think that you’ll have to turn your brain inside out to be able to understand a Japanese person or say something to him (by the way, the Japanese have exactly the same feelings when learning English or Russian).

It must be remembered that in a Japanese sentence the predicate always comes at the end, hence the following rules for a simple common sentence: the object is located between the subject and the predicate, the adverbial is before or after the subject, but always before the predicate.

The next iron rule is that the definition always precedes the word being defined. And the last rule is that service particles (case markers, postpositions, particles, connectives, conjunctions) are always placed after the word to which they relate.

It is believed that at the end of a sentence there is always important information that can radically change the meaning of the entire sentence.

Compare:

「あなたはきれいです。」Anata wa kirei desu (You are beautiful)

And

「あなたはきれいじゃありません。」Anata wa kirei ja arimasen (You are ugly).

You will not know whether this statement is affirmative or negative until you listen to it to the end. In the Russian language, we already understand in the middle, and sometimes even at the beginning, what type of sentence it will be.

Take, for example, this statement:

「あのラーメン屋は人気・・・」Ano ramenya wa ninki...This ramen shop is popular...

The end of a phrase can be anything: it can be a statement (です, desu), a negation (じゃありません, ja arimasen), a question (ですか, desu ka) and a past tense (でした, deshita). In any case, you will have to listen to the end of the sentence, because the verb is always at the end of the sentence.

Now, using a specific example, let's look at a more natural word order in Japanese. In which of the following sentences do you think the sentence structure looks most natural?

Watashi wa kinou Shibuya de Emma to eiga o mimashita

Yesterday, in Shibuya, I watched a movie with Emma.

Watashi wa Shibuya de Emma to eiga o kinou mimashita

I, in Shibuya, with Emma, watched a movie yesterday.

Watashi wa Emma to eiga o kinou Shibuya de mimashita.

Emma and I watched a movie yesterday in Shibuya.

Watashi wa eiga o kinou shibuya de Emma to mimashita.

Yesterday, I watched a movie in Shibuya with Emma.

For the Japanese, the most natural word order is the one in the first sentence. So the word order diagram would look like this:

(Subject or topic of the sentence) + tense + place + indirect object + object + action verb.

Following this pattern, we understand how sentences are constructed in Japanese and can create the following examples:

Watashi wa ashita Ginza de kazoku to sushi o tabemasu.

Tomorrow, in Ginza, with my family, I will eat sushi.

Satou san wa doyoubi kouen de tomodachi to jogging wo shimasu.

Sato-san will be running in the park with a friend on Saturday.

Write two sentences in Japanese in the comments using the diagram above.

Do you want to learn to read Japanese in a week? Follow the link and you will find out how to do it!

We recommend:

Throwing out the parts

You may omit any part of a compound sentence if it is implied by the context.

Example

スミス。

Show/hide translation

Smith: (I) don't like it here. Lee: Why? Smith: Because it's noisy.

If the first part is discarded, it is still necessary to add 「です」, 「だ」, or 「な」 as if the first clause was present.

- library 【と・しょ・かん】

- ここ - here

- あまり - not very (when used with a negative form)

- 好き【す・き】 - liking

Home page 。

Show/hide translation

Lee: Even though (it's) a library, it's always noisy, right? Smith: So (I don't really like it here).

Everything else remains the same as if both sentences were present.

- ですから、あまり好きじゃないです。

- なので、あまり好きじゃないです。

You can even throw out both parts of a compound sentence, as in the following dialogue.

Basic structure

The basic structure looks like this:

Subject + Verb + Object

Subject + Predicate + Object

For example, “I love you”, “I eat food”:

| Subject | Verb | An object | |

| 我 | 爱 | 你 | 。 |

| wǒ | ài | nǐ | 。 |

| I love you. | |||

| 我 | 吃 | 饭 | 。 |

| wǒ | chī | fan | 。 |

| I eat food. | |||

| 他 | 打 | 篮球 | 。 |

| tā | dǎ | lánqiú | 。 |

| He plays basketball. | |||

1) Reduction of sounds [and] and [y]

If the sounds [i] and [u] in Japanese are located between 2 voiceless consonant sounds (for example, [k], [s], [p], [t]), then they are reduced, that is, they are partially not pronounced :

ひと → reads “hto” (and NOT hito!), the sound [and] is partially reduced / translation of the word: “man” した → reads “sta” (and NOT sita!) (the sound “s” should be pronounced closer to “shch” , while the sound itself should be pronounced briefly. In the first lesson, we explained in detail the features of the pronunciation of Hiragana sounds); the sound [and] is partially reduced / translation of the word: “bottom, below” ふとい → read “ftoy” (and NOT futoy!), the sound [u] is partially reduced (drops out) / “thick” あした → read “ashta”, sound [ and] is partially reduced / translation of the word: “tomorrow” ふた → reads “fta”, the sound [u] is partially reduced / translation of the word: “lid” よろしく → reads “eroshchku”, sound [and] is partially reduced / translation: “hello”です → read “des”, the sound [u] at the end is partially reduced / translation: verb link “is, to be”

Adding other parts of speech (details) to the base sentence

Time in Chinese sentence

Circumstance of time ( when does the action take place?

) is placed either at the beginning of the sentence or immediately after the subject (subject). The circumstance of time answers the question when

the action takes place,

at what time

, in what year, in what season, on what day, and so on.

| Subject | circumstance of time | Verb phrase | |

| 我 | 明天 | 休息 | 。 |

| wǒ | míngtiān | xiūxí | 。 |

| I rest tomorrow. | |||

| 你 | 常常 | 洗澡 | 。 |

| nǐ | changchang | xǐzǎo | 。 |

| You wash often. | |||

| 他 | 星期三 | 去 | 。 |

| tā | xīngqīsān | qù | 。 |

| He's leaving on Wednesday. | |||

Complement of place (object). 在 as an auxiliary verb

We express the place of action of the verb, where the action takes place

. At this point we will learn to express an action that occurs in some place

.

For example, “I live in Russia

,” “I study

in China,

” and so on. This topic will feature the verb 在 zài, which is translated as: to be in, in. Let us pay special attention to the position of this verb.

在 can be an auxiliary verb (according to another classification, the preposition “in”), and can stand together with a place complement before the main verb. As a rule, the main verb is disyllabic and consists of two hieroglyphs. The verb connective rule works here.

Structure

在 + Place + Two-syllable verb (+ Object)

In modern spoken Chinese, irregularities occur, and 在 is increasingly being placed after disyllabic verbs. But for 80% of the Chinese surveyed, putting 在 after such a verb is considered an error.

| Subject | circumstance of time | Place | Verb phrase | |

| 她 | 1990 | 在俄罗斯 | 出生 | 。 |

| tā | yījiǔjiǔ líng nián | zài èluósī | chūshēng | 。 |

| She was born in 1990 in Russia. | ||||

When the object of place (object) is placed after the verb. 在 as a verb object

If the verb is monosyllabic (consists of one hieroglyph), then most often 在 is placed after the verb. Such monosyllabic verbs could be 走 zǒu to walk, 停 tíng to stop, 住 zhù to live, 坐 zuò to sit down, and 站 zhàn to get up. In this case, 在 is not considered a preposition, but rather the direction of action of the verb; According to Chinese logic, it shows where the action is taking place. 在 will be a verb complement, and serves as an indicator of the direction of action of this very monosyllabic verb.

Structure

Monosyllabic verb + 在 + Place

Phonetics

When reconstructing the phonetics of the Old Japanese language, researchers relied on data from comparative linguistics: analysis of synchronic texts in Middle Chinese, studies of phonetic changes that occurred in Japanese, and comparative analysis of the Ryukyuan languages. Although most Japanese ancient texts were created in the language of the courtiers in Asuka and Nara, in central Japan, the creators of Manyoshu used southern and eastern dialects.

Old Japanese differed significantly from later stages of language development. Analysis of man'yogana and jodai tokushu Kanazukai made it possible to reconstruct phonetics.

Transcriptions of Old Japanese are available in the Kojiki, Nihon Shoki, and Manyoshu. However, if the Kojiki distinguishes between the syllables /mo1/ and /mo2/, then the last two treatises do not. The Kojiki was compiled before the Nihon Shoki and the Manyoshu, so it reflects pronunciation that later became obsolete.

Other differences between Old Japanese and modern Japanese:

Some researchers believe that Old Japanese may be related to some extinct languages from the Korean peninsula, in particular Goguryeo, but the genetic connections of Japanese with any existing languages other than Ryukyuan remain hypothetical. See also Japanese-Ryukyuan languages#Classification.

Syllables

Old Japanese had about 88 syllables.

(Japanese 促音, consonant doubling), shown here with /Q/, and hatsuon

(Japanese 撥音, final syllabic “n”, forming a separate mora) did not exist or were not recorded.

However, in 奈能利曽-奈能僧 (762 AD) the reading was nano2sso2

, 意芝沙加-於佐箇 (720 AD) and

bokun

(傍訓) オムサカ in mid-Heian suggested the reading

o2ssaka

or

o2nsaka

.

Neither Sokuon nor Hatsuon have yet created new pestilence.

| a | i | u | e | o | |||

| ka | ki1 | ki2 | ku | ke1 | ke2 | ko1 | ko2 |

| ga | gi1 | gi2 | gu | ge1 | ge2 | go1 | go2 |

| sa | si | su | se | so1 | so2 | ||

| za | zi | zu | ze | zo1 | zo2 | ||

| ta | ti | tu | te | to1 | to2 | ||

| da | di | du | de | do1 | do2 | ||

| na | ni | nu | ne | no1 | no2 | ||

| pa | pi1 | pi2 | pu | pe1 | pe2 | po | |

| ba | bi1 | bi2 | bu | be1 | be2 | bo | |

| ma | mi1 | mi2 | mu | me1 | me2 | mo1 | mo2 |

| ya | yu | ye | yo1 | yo2 | |||

| ra | ri | ru | re | ro1 | ro2 | ||

| wa | wi | we | wo | ||||

Soon after the creation of the Kojiki, the differences between mo1 and mo2 were leveled out, and the number of syllables became 87.

There are several hypotheses to explain the double syllables:

Transcriptions

It should be kept in mind that transcription systems do not reflect all hypotheses about the phonetics of Old Japanese, and also that subscripts can refer to both a vowel and a consonant sound.

There are several transcription systems. One places the diaeresis above the vowel: ï, ë, ö (i2, e2, o2). This system has the following disadvantages:

Another system involves the use of subscripts.

Vowels

Vowel alternation

There was an affix “sacred” (Japanese 斎 ' i- or

Yu-'

). It is assumed to read /*yi/.

Consonants

In Old Japanese, according to reconstructions, the following consonants existed[3]:

| Labial | Coronal | Palatal | Postopalatines | ||

| Deaf noisy | * | * | (*t͡s) | * | * |

| Prenasalized voiced noisy | * | * | * | * | |

| Nasals | * | * | |||

| Approximant/one-beat | * | * | * | ||

Noisy consonants

Voiceless noisy consonants /p, t, s, k/ were correlated with voiced prenasalized sounds. Prenasalization survived into medieval Japanese, and in northern dialects it persists to this day.

Voiceless labial noisy

The sound /h/ of modern Japanese was realized in Old Japanese as

. This conclusion was made by linguists based on the following analysis.

The voiceless pair for the sound /b/ is /p/.

It is believed that between the 9th and 17th centuries the sound was pronounced as [ɸ]. Dialectological evidence suggests that it must have once been realized as

Voiceless coronal noisy

Approximant and single-stress consonants

Phonetic resolutions

In 1934, Hideyo Arisaka (Japanese: 有坂秀世Arisaka Hideyo

see also

Duration of action by time

Supplement that answers the question of how long the effect lasts

of the verb is placed after the verb or after its verbal complement if there is this same verbal complement. Therefore, very often the verb is duplicated twice, or the duration of the action stands between the verb and the object.

| Subject | Circumstance of time (when?) | Complement of place (object) | Verb phrase | Complement of place (object) | Addition of duration of time (how long?) | |

| 我 | 住 | 在北京 | 三年了 | 。 | ||

| wǒ | zhù | zài běijīng | sān nián le | 。 | ||

| I have been living in Beijing for three years. | ||||||

| 我 | 去年 | 在上海 | 学了 | 三个月 | 。 | |

| wǒ | qùnián | zài shànghǎi | xuele | sān gè yuè | 。 | |

| Last year I studied in Shanghai for three months. | ||||||

| 她 | 昨天 | 在家里 | 看电视看了 | 十个小时 | 。 | |

| tā | zuótiān | zài jiālǐ | kàn diànshì kànle | shí gè xiǎoshí | 。 | |

| Yesterday she watched TV for ten hours at home. | ||||||

Verb adverb and expression of the mode of action of the verb

How, in what way the action is performed

discussed in detail in a separate article. And in this article we will look at how a verbal adverb is used to express how the action of a verb is performed. For example, “I dance joyfully”, “I run quickly”. A verbal adverb is created according to the structure of an adjective + 地. - this is a particle that makes an adjective - a verbal adverb with the suffix -o

.

For example, fast -

>

fast

.

| Subject | Circumstance of time (when?) | Verb adverb | Complement of place (object) | Verb | |

| 我 | 高兴地 | 说了 | 。 | ||

| wǒ | gāoxìng de | shuōle | 。 | ||

| I said happily. | |||||

| 顾客 | 买完东西以后 | 满意地 | 走了 | 。 | |

| gùkè | mǎi wán dōngxi yǐhòu | mǎnyì de | zǒule | 。 | |

| Customers leave happy after purchasing. | |||||

| 她 | 喝醉的时候 | 疯狂地 | 在路上 | 跳舞 | 。 |

| tā | hē zuì de shíhou | fēngkuáng de | zài lùshàng | tiàowǔ | 。 |

| When she gets drunk, she dances wildly in the street. | |||||

Additional phrase expressing a means to an end

Let's add a phrase to the sentence that expresses the means to achieve the goal. We will tell you how the action is achieved

. The structure of this additional phrase is 用 + object. 用 translates to "use". And the object is the means by which the action is achieved. In Russian we will say “I eat food with chopsticks,” and in Chinese logic this phrase will literally be translated as “I use chopsticks and eat food.” Essentially, a sequence of actions is inserted into the base sentence. This phrase is inserted before the main verb.

Writing

Japanese words were first written using Chinese characters as early as the second half of the fifth century AD (Inariyama Kofun, part of the Kofun period). However, the earliest Japanese texts are written in wenyang, although they can be read in Japanese using kambun. Some of these Chinese-language texts show influence from Japanese grammar, for example, sometimes the predicate is placed after the direct object, as in Japanese, rather than before it (as in Wenyang). In such texts, Japanese particles can be written phonetically in Chinese characters.

Over time, the phonetic use of kanji gained increasing popularity, eventually giving rise to man'yōgana. In the Kojiki, man'yōgana was already used to record personal names and place names, and in the Man'yōshū text it occupies a significant place.

On the other hand, Chinese characters are beginning to be used semantically, to denote Japanese words related to Chinese in meaning, and not in sound. For example, a whale is familiar. 谷, pinyin gǔ

, pal. gu

, literally: "valley" began to spell the Japanese word

tani

(Japanese: たに, "valley").

Later, both words with approximately similar sounds and words with similar meanings began to be written using Chinese characters. tribute

was written using 谷(Japanese だに, “at least”, “in any case”).

夢尓谷不見在之物乎 yume ni dani/ mizu arishi mono about “That which cannot be seen even in a dream.”