The table shows personal pronouns used in neutral-polite speech:

The pronoun あなた, if used in conversation, is only when addressing an elder to a younger person or when addressing someone equal in age or social status.

ぼく – I (in male speech)

Examples of using personal pronouns as subjects:

The plural of personal pronouns is expressed using suffixes: たち、ども、がた、ら

Source

1st person pronouns

Let's start with 1st person pronouns. Japanese has more of them than other languages. This is due to the fact that there are pronouns that are used only by men or, conversely, only by women, and pronouns can also differ in the degree of politeness.

私 (watashi) is a universal pronoun for the 1st person. It can be used by both men and women. Sometimes the same pronoun is pronounced as わたくし (watakushi) - this form is used when they want to sound more polite, mainly in formal settings, as well as when meeting for the first time. There is also a female version, which sounds like あたし (atashi), it is used only by girls, girls, and it sounds a little childish.

There are quite a few ways to form the plural of personal pronouns. All of them are built on the addition of various plural suffixes at the end of a word. Suffixes can be: がた (gata), たち (tachi), ら (ra).

To form the plural of the pronoun 私 (watashi), use the suffix たち (tachi). The resulting word is 私たち (watashitachi), “we.” This word is also universal in its use.

私は学生です。 Watashi wa gakusei desu.

Watashitachi wa kono ie ni sunde imasu.

We live in this house.

Men can also use 僕 (boku) about themselves if they want to sound modest, and 俺 (ore) in a more casual, friendly environment. 俺 (ore) should not be used when communicating with superiors; it is mainly used when communicating with friends, family, equals or lower social status. When communicating with superiors, it is more appropriate to say 僕 (boku) - it is no coincidence that one of the meanings of this character is servant. The speaker thus emphasizes that he is below the interlocutor. The plurals of these are 僕ら (bokura) and 俺ら (orera), respectively. These pronouns are used mainly by men, although there are cases when girls also refer to themselves as 僕 (boku), but this is slang and rather the exception to the rule.

Boku wa kono kaisha ni tsutomete orimasu.

I work for this company. (Very polite).

俺ら、腹減ったぞ。 Orera, hara hetta zo.

We're hungry. (Colloquial).

If we talk about female pronouns of the 1st person, then it is also worth mentioning the word うち (uchi). This pronoun is not used as often in Tokyo, but is more common in the Kansai region. The word うち (uchi) itself can be translated as “house, inside, ours.” It has no plural form.

Young children often use their own name instead of first person pronouns. For example:

健太は遊びに行きたいよ。 Kenta wa asobi ni ikitai yo.

Kenta wants to go play.

我々 (wareware) – “we”, a pronoun used by the heads of organizations and the military. This is “we”, which emphasizes that a person speaks as a representative, a leader of a community.

Ware-ware wa uchuujin da.

If there is communication between two companies, then we will denote ourselves, our side, our company with the word こちら (kochira). For example:

こちらから連絡いたします。 Kochira kara renraku itashimasu.

We (from our side) will contact you.

Another thing to consider is that the Japanese often omit first person pronouns. This is a little unusual. For example, when talking about ourselves, we will say this: “My name is Anya. I am 23 years old. I live in Moscow. I study at University…". Every sentence includes “I” or “me, me.” If we say the same thing in Japanese, we will use 私 (watashi) only in the first sentence, and in subsequent sentences we will omit this word.

Plural suffixes

| Polivanov | Hiragana | Kanji | Gender | Notes |

| Tati/dati | たち | 達 | Men and women | Forms the plural of nouns and pronouns. 私watashi becomes 私 watashichi . The exception is 友達tomodachi - “friend”. Attached to the name means "...and others": "山田達" - Yamadatachi , "Yamada and others" |

| Kata/Gata | がた | 方 | Men and women | More polite than "tati" |

| Domo | ども | 共 | Men and women | Modestly. Creates a feeling of disconnection and may be considered rude |

| Ra | ら | 等 | Men and women | Informal (彼ら, karera ; 僕ら, bokura ; 俺ら, orera ; 奴ら, yatsura ; あいつら, aitsura ). Used with informal pronouns and especially with rude words: お前ら, omaera |

Pronouns in Japanese 2nd person

あなた (anata) translates to “You” and is a singular pronoun. The plural would be あなたたち (anatatachi), or, if we want to sound more polite, then あなたがた (anatagata). The word あなた (anata) should not be used too often in speech. Strictly speaking, it is appropriate to use it only when you do not know the name of your interlocutor. In other cases, instead of あなた (anata), they usually use the surname or first name of the interlocutor plus an address suffix, for example: 田中さん (Tanaka-san). Yes, it sounds a little strange if translated into Russian literally. 田中さんはどこに住んでいますか。 (Tanaka-san wa doko ni sunde imasu ka.) – “Where does Tanaka live?” (and we ask this directly from Tanaka, as if calling him in the 3rd person). Literally, this can be translated as “Tanaka, where do you live?” And the Japanese use this turn of phrase much more often, which is あなた (anata).

Anata no namae wa nan desu ka.

Yamada-san wa koko ni yoku kimasu ka.

Yamada, do you come here often?

Also, the word あなた (anata) is what a Japanese wife usually uses to address her husband. In this case, it can be translated as “you” or “dear”.

There is also a shortened form あんた (anta), which is more common in colloquial speech.

"You" in Japanese is 君 (kimi). This pronoun is used much more often by men, usually in relation to girls or inferiors. 君 (kimi) is often used by superiors in relation to subordinates. Women use this pronoun much less often. The same rule applies here: usually the Japanese do not say “you” or “you”, but call the interlocutor by first or last name. The plural form of this pronoun is 君たち (kimitachi) - “you”.

君を守りたい。 Kimi wo mamoritai.

I want to protect you.

There are also ruder ways to say "you" in Japanese. Firstly, it is お前 (omae). This is what we say to a person we don’t really respect. Men often resort to this pronoun. The plural form of this pronoun is お前ら (omaera).

Another swear word for “you” is てめえ (temee). It can also often be heard in anime when a hero challenges an opponent or when he is very angry with his interlocutor.

By analogy with こちら (kochira), which means “we, our side,” in business communication the word そちら (sochira) is used to mean “you, your side.”

Sochira no tsugou no ii jikan wo ochiete kudasaimasen ka.

Could you tell me what time is convenient for you?

Thus, depending on the 2nd person pronoun that we choose, we can show either our respectful attitude towards the interlocutor (I repeat, the most successful way is to use not “you” or “you” as address, but the name of the interlocutor), or complete disregard, as in the case of お前 (omae) and 貴様 (kisama).

Other pronouns

They are given in interrogative form, but interrogative and positive pronouns differ only in the presence/absence of a question mark.

| Relative pronouns | Demonstrative pronouns | ||||

| Pronoun | Kanji | Polivanov | Pronoun | Kanji | Polivanov |

| Who? Whose? | 誰? 誰の? | Dare? Dare but? | When? | 何時? | Itsu? |

| What is the price)? How many years)? | 幾ら? 幾つ? | Ikura? Ikutsu? | This (closer to the speaker than to the interlocutor) This (closer to the interlocutor than to the speaker) That | この その あの | kono sono ano |

| What? Whose? | 何?何の? | Nani? Nani but? | Which? Such? | どんなの? そんなの? | Donna but? Sonna but? |

| Why? From what? | なぜ?何で? | Naze? Nanda? | Where? Where? | どこから? どこに? | Doko kara? Doko ni? |

Pronouns in Japanese 3rd person

The most neutral and universal pronoun for the 3rd person is あの人 (anohito). It is translated both as “he” and as “she”, that is, it is used regardless of the gender of the person we are talking about. The plural of it is あの人達 (anohitotachi), “they.” If we want to sound more polite, we can use あの方 (anokata), which also translates to either “he” or “she.” And the plural of it is あの方々 (anokatagata), “they”.

Anohito wa Sasaki-san desu.

あの方々は大使です。 Ano kata-gata wa taishi desu.

These gentlemen are ambassadors.

Additionally, 彼 (kare) is used to indicate "he". It is usually used in relation to closer people, friends. It can also mean "boyfriend, lover." The plural would be 彼ら (karera), “they (men).”

彼はまだ若い。 Kare wa mada wakai.

To say "she" you can use 彼女 (kanojo). This word is also used to refer to one's girlfriend.

昨日彼女と喧嘩した。 Kinou kanojo to kenka shita.

Yesterday I had a fight with my girlfriend.

The plural form of 彼女 (kanojo) is 彼女たち (kanojotachi), “they (girls).”

(

3 ratings, average: 5.00 out of 5) Loading.

Source

Nominal suffixes

In the Japanese language, there is a whole set of so-called nominal suffixes

, that is, suffixes added in colloquial speech to first names, surnames, nicknames and other words denoting an interlocutor or a third party. They are used to indicate the social relationship between the speaker and the one being spoken about. The choice of suffix is determined by the character of the speaker (normal, rude, very polite), their attitude towards the listener (common politeness, respect, ingratiation, rudeness, arrogance), their position in society and the situation in which the conversation takes place (one-on-one, in a circle of loved ones friends, between colleagues, between strangers, in public). What follows is a list of some of these suffixes (in order of increasing "respectfulness") and their common meanings.

—chan

— A close analogue of the “diminutive” suffixes of the Russian language. Usually used in relation to a junior or inferior in a social sense, with whom a close relationship develops. There is an element of baby talk in the use of this suffix. Typically used when adults address children, boys address their girlfriends, girlfriends address each other, and small children address each other. The use of this suffix in relation to people who are not very close, equal in status to the speaker, is impolite. Let's say, if a guy addresses a girl his age in this way, with whom he is not “having an affair,” then he is being inappropriate. A girl who addresses a guy of her own age in this way, with whom she is not “having an affair,” is essentially being rude.

—kun

- An analogue of the address “comrade”. Most often used between men or in relation to guys. Indicates, rather, a certain “officiality” of, nevertheless, close relationships. Let's say, between classmates, partners or friends. It can also be used in relation to juniors or inferior in a social sense, when there is no need to focus on this circumstance.

—yan

— Kansai analogue of

“-chan”

and

“-kun”

.

—pyon

- Children's version of

"-kun"

.

—tti (cchi)

- Children's version of

"-chan"

(cf.

"Tamagotti"

).

—without suffix

— Close relationships, but without babying. The usual address of adults to teenage children, friends to each other, etc. If a person does not use suffixes at all, then this is a clear indicator of rudeness. Calling by last name without a suffix is a sign of familiar, but “detached” relationships (a typical example is the relationship of schoolchildren or students).

—san

— Analogous to the Russian “Mr./Madam.” A general indication of respect. Often used to communicate with strangers, or when all other suffixes are inappropriate. Used in relation to elders, including older relatives (brothers, sisters, parents).

—khan

— Kansai equivalent of

“-san”

.

—si (shi)

- “Mr.”, used exclusively in official documents after the surname.

—fujin

— “Madam”, used exclusively in official documents after the surname.

—kouhai

- Address to the younger one. Especially often - at school in relation to those who are younger than the speaker.

—senpai

— Appeal to the elder. Especially often - at school in relation to those who are older than the speaker.

—dono

- Rare suffix. Respectful address to an equal or superior, but slightly different in position. Currently considered obsolete and practically not found in communication. In ancient times, it was actively used when samurai addressed each other.

—sensei

- "Teacher". Used to refer to teachers and lecturers themselves, as well as doctors and politicians.

—Senshu

- "Athlete". Used to refer to famous athletes.

—zeki

- “Sumo wrestler.” Used to refer to famous sumo wrestlers.

—ue (ue)

- "Senior". A rare and outdated respectful suffix used for older family members. Not used with names - only with designations of position in the family (“father”, “mother”, “brother”).

—herself (sama)

- The highest degree of respect. Appeal to gods and spirits, to spiritual authorities, girls to lovers, servants to noble masters, etc. Roughly translated into Russian as “respected, dear, venerable.”

—jin

- "One of".

"Saya-jin"

means "one of Saya."

—tachi

- "And friends".

"Goku-tachi"

- "Goku and his friends."

—gumi

- “Team, group, party.”

"Kenshin-gumi"

- "Team Kenshin".

Links[edit]

- Noguchi, Tora (1997). "Two types of pronouns and variable binding." Language

.

73

(4):770–797. DOI: 10.1353/lan.1997.0021. S2CID 143722779. - Takehiro

(2002) . Kodansha. - ^ a b c d e f

Akiyama, Nobuo;

Akiyama, Carol (2002). Japanese Grammar

. Educational Barron. ISBN 0764120611. - Ishiyama, Osama (2008). Diachronic perspectives on personal pronouns in Japanese

(Ph.D.). State University of New York at Buffalo. - Maynard, Senko K.: "Introduction to Japanese Grammar and Communication Strategies", p. 45. The Japan Times, 4th edition, 1993. ISBN 4-7890-0542-9

- "Many Ways to Say 'I' in Japanese | nihonshok". nihonshock.com

. Retrieved October 17, 2021. - Hatasa, Yukiko Abe; Hatasa, Kazumi; Makino, Seiichi (2014). Nakama 1: The Context of Japanese Communication Culture

. Cengage Learning. item 314. ISBN 9781285981451. - Nechaeva L.T. “Japanese for Beginners”, 2001, Moscow Lyceum Publishing House, ISBN 5-7611-0291-9

- Maidonova S.V. “The Complete Course of the Japanese Language”, 2009, Astrel Publishing House, ISBN 978-5-17-100807-9

- ^ B s d e e

8.1.

Pronouns sf.airnet.ne.jp.

Retrieved October 21, 2007. - ^ a b c

Personal pronouns in Japanese

Japan Link

. Retrieved October 21, 2007. - "Language Log" Japanese First Person Pronouns". languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu

. - "old boy" Kanjidict.com. Retrieved May 7, 2012.

- "He" . Kanjidict.com. Retrieved May 7, 2012.

Usage and etymology

Unlike the real ones

people and things,

absent

people and things can be mentioned by naming;

for example, by instantiating the class "house" (in a context where there is only one house) and representing things in relation to the present, named and sui generis people or things might be "I'm going home", "I'm going to Miyazaki's", " I'm going to see the mayor," "I'm going to see my mom," or "I'm going to see my mother's friend." Functionally, deictic classifiers

not only indicate that the person or thing being referred to has a spatial location or interactive role, but also classify it to some extent.

In addition, Japanese pronouns

are limited by the type of situation (case): who is talking to whom about what and through what medium (oral or written, staged or confidential). In this sense, when a man talks to his male friends, the set of pronouns available to him is different from those available when a man of the same age talks to his wife and, conversely, when a woman talks to her husband. . These differences in the presence of pronouns are determined by case.

In linguistics, generativists and other structuralists propose that Japanese has no pronouns as such because, unlike pronouns in most other languages that have them, these words are syntactically and morphologically identical to nouns. However, as functionalists point out, these words act as personal references, indicators, and reflexives, just like pronouns in other languages.

Japanese has many pronouns, varying in formality, gender, age, and the relative social status of speaker and audience. Additionally, pronouns are an open class, with existing nouns being used as new pronouns with some frequency. It continues; a recent example is jibun (自分, i), which is now used as a casual first-person pronoun by some young people.

Pronouns are used less frequently in Japanese than in many other languages, mainly because there are no grammatical requirements for including a subject in a sentence. This means that pronouns can rarely be translated one-to-one from English to Japanese.

Common English personal pronouns such as "I", "you" and "they" have no other meanings or connotations. However, most personal pronouns do have meaning in Japanese. Consider, for example, two words corresponding to the English pronoun "I": 私 (watashi) also means "private" or "personal". 僕 (boku) gives the impression of a man; it is usually used by men, especially when they are young.

Japanese words referring to other people are part of a general system of honorific speech and should be understood in that context. The choice of pronoun depends on the social status of the speaker (compared to the listener) and on the subjects and objects of the sentence.

First person pronouns (such as watashi, 私) and second person pronouns (such as anata, 貴方) are used in formal contexts (however, the latter can be considered rude). In many sentences, the pronouns meaning "I" and "you" are omitted in Japanese when the meaning is still clear.

When the topic of a sentence is required for clarity, the particle wa (は) is used, but this is not required if the topic can be inferred from the context. Additionally, verbs are often used that imply the subject and/or indirect object of a sentence in certain contexts: kureru (くれる) means "to give" in the sense that "someone other than me gives something to me or to someone very close. to me." Ageru (あげる) also means "to give", but in the sense of "someone giving something to someone other than me". This often makes pronouns unnecessary because they can be inferred out of context.

A Japanese speaker can only express his emotions directly, as he cannot know the true mental state of anyone else. Thus, in sentences consisting of a single adjective (often ending in -shii), the speaker is often assumed to be the subject. For example, the adjective sabishii (寂しい) can be a complete sentence that means "I am lonely." sabishi will be used instead

(寂しそう) "seems lonely."

Similarly, neko ga hoshii

(猫が欲しい) "I want a cat", as opposed to

neko wo hoshigatte iru

(猫を欲しがってい) "seems to want a cat" when referring to others. Thus, the first person pronoun is usually not used unless the speaker wants to emphasize the fact that he is referring to himself, or if it is necessary to make it clear.

In some contexts, it may be considered rude to refer to the listener (the second person) through a pronoun. If a second person is required, the listener's last name is usually used with the suffix -san or another title (for example, “customer,” “teacher,” or “boss”).

Gender differences in spoken Japanese also pose another problem, as men and women refer to themselves with different pronouns. Social position also determines how people feel about themselves, as well as how they feel about other people.

Japanese first person pronouns

Japanese first person pronouns by speakers and situations according to Yuko Saegusa, Regarding the first person

Japanese

Native Speakers' Pronouns (2009)

Elementary School Students' First Person Pronouns (2008)

| Speaker | Situation | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| female | To friends | teach 49% | Name 26% | atashi 15% |

| In family | Name 33% | atashi 29% | teach 23% | |

| In class | Watashi 86% | atashi 7% | teach 6% | |

| To an unknown visitor | watashi 75% | atashi, name, teach 8% | ||

| To the class teacher | watashi 66% | Name 13% | atashi 9% | |

| man | To friends | ore 72% | side 19% | Name 4% |

| In family | ore 62% | side 23% | teach 6% | |

| In class | side 85% | ore 13% | Name, nickname 1% each | |

| To an unknown visitor | side 64% | ore 26% | Name 4% | |

| To the class teacher | side 67% | ore 27% | Name 3% | |

University Students' First Person Pronouns (2009)

| Speaker | Situation | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| female | To friends | teach 39% | atashi 30% | watashi 22% |

| In family | atashi 28% | Name 27% | teach 18% | |

| In class | Watashi 89% | atashi 7% | jibun 3% | |

| To an unknown visitor | Watashi 81% | atashi 10% | jibun 6% | |

| To the class teacher | watashi 77% | atashi 17% | jibun 7% | |

| man | To friends | ore 87% | teach 4% | Watashi, Jibun 2% each |

| In family | ore 88% | boku, jibun 5% each | ||

| In class | watashi 48% | jibun 28% | side 22% | |

| To an unknown visitor | side 36% | jibun 29% | watashi 22% | |

| To the class teacher | jibun 38% | side 29% | watashi 22% | |

Demonstrative and interrogative pronouns

Demonstrative words that function as pronouns, adjectives or adverbs are divided into four groups. Words starting with co-

indicate something close to the speaker (so-called

proximal

demonstrative words).

Those beginning with SO-

indicate separation from the speaker or proximity to the listener (

medial

), while those beginning with

a-

indicate greater distance (

distal

).

Question words used in questions begin with do-

.

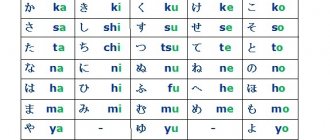

Demonstrations are usually written in hiragana.

| Romaji | Hiragana | Kanji | I mean |

| Korea | これ | 此れ | this thing / these things (next to the speaker) |

| hurts | それ | 其れ | that thing/those things (near the listener) |

| are | あ れ | 彼れ | this thing / these things (away from the speaker and the listener) |

| Dore | どれ | 何れ | which things)? |

| kochira or kotchi | こちら / こっち | 此方 | this/here (next to the speaker) |

| Sochira or Sochi | そちら / そっち | 其方 | what/there (near the listener) |

| achira or atchi | あちら / あっち | 彼方 | this / there (away from the speaker and listener) |

| daughter or daughter | どちら / どっち | 何方 | What is where |

Nominal suffixes

In the Japanese language, there is a whole set of so-called nominal suffixes, that is, suffixes added in colloquial speech to first names, surnames, nicknames and other words denoting an interlocutor or a third party. They are used to indicate the social relationship between the speaker and the one being spoken about.

The choice of suffix is determined by the character of the speaker (normal, rude, very polite), their attitude towards the listener (common politeness, respect, ingratiation, rudeness, arrogance), their position in society and the situation in which the conversation takes place (one-on-one, in a circle of loved ones friends, between colleagues, between strangers, in public).

What follows is a list of some of these suffixes (in order of increasing "respectfulness") and their common meanings.

-chan (chan) - A close analogue of the “diminutive” suffixes of the Russian language. Usually used in relation to a junior or inferior in a social sense, with whom a close relationship develops. There is an element of baby talk in the use of this suffix. Typically used when adults address children, boys address their girlfriends, girlfriends address each other, and small children address each other. The use of this suffix in relation to people who are not very close, equal in status to the speaker, is impolite. Let's say, if a guy addresses a girl his age in this way, with whom he is not “having an affair,” then he is being inappropriate. A girl who addresses a guy of her own age in this way, with whom she is not “having an affair,” is essentially being rude.

-kun (kun) - An analogue of the address “comrade”. Most often used between men or in relation to guys. Indicates, rather, a certain “officiality” of, nevertheless, close relationships. Let's say, between classmates, partners or friends. It can also be used in relation to juniors or inferior in a social sense, when there is no need to focus on this circumstance.

-yan (yan) - Kansai analogue of “-chan” and “-kun”.

-pyon (pyon) - Children's version of "-kun".

-tti (cchi) - Children's version of "-chan" (cf. "Tamagotti").

-without a suffix - Close relationships, but without “lisping.” The usual address of adults to teenage children, friends to each other, etc. If a person does not use suffixes at all, then this is a clear indicator of rudeness. Calling by last name without a suffix is a sign of familiar, but “detached” relationships (a typical example is the relationship of schoolchildren or students).

See also: Where did Jewish surnames come from?

-san (san) - An analogue of the Russian “Mr./Madam”. A general indication of respect. Often used to communicate with strangers, or when all other suffixes are inappropriate. Used in relation to elders, including older relatives (brothers, sisters, parents).

-han (han) - Kansai equivalent of “-san”.

-si (shi) - “Mr,” used exclusively in official documents after the surname.

-fujin - “Mistress”, used exclusively in official documents after the surname.

-kohai (kouhai) - Appeal to the younger. Especially often - at school in relation to those who are younger than the speaker.

-senpai (senpai) - Appeal to an elder. Especially often - at school in relation to those who are older than the speaker.

-dono (dono) - Rare suffix. Respectful address to an equal or superior, but slightly different in position. Currently considered obsolete and practically not found in communication. In ancient times, it was actively used when samurai addressed each other.

-sensei - “Teacher”. Used to refer to teachers and lecturers themselves, as well as doctors and politicians.

-senshu (senshu) - “Sportsman.” Used to refer to famous athletes.

-zeki (zeki) - “Sumo wrestler.” Used to refer to famous sumo wrestlers.

-ue (ue) - “Elder”. A rare and outdated respectful suffix used for older family members. Not used with names - only with designations of position in the family (“father”, “mother”, “brother”).

-sama (sama) - The highest degree of respect. Appeal to gods and spirits, to spiritual authorities, girls to lovers, servants to noble masters, etc. Roughly translated into Russian as “respected, dear, venerable.”

-dzin (jin) - “One of.” "Saya-jin" means "one of Saya."

-tachi (tachi) - “And friends.” "Goku-tachi" - "Goku and his friends."

See also: 20 female body types with photos

-gumi (gumi) - “Team, group, party.” "Kenshin-gumi" - "Team Kenshin".

Personal pronouns

In addition to nominal suffixes, Japan also uses many different ways to address each other and refer to themselves using personal pronouns. The choice of pronoun is determined by the social laws already mentioned above. The following is a list of some of these pronouns.

Group with the meaning "I"

Watashi - Polite option. Recommended for use by foreigners. Typically used by men. Infrequently used in colloquial speech, as it carries a connotation of "high style".

Atashi - Polite option. Recommended for use by foreigners. Typically used by women. Or gays. ^_^ Not used when communicating with high-ranking individuals.

Watakushi - A very polite female version.

Washi - An outdated polite option. Doesn't depend on gender.

Wai - Kansai equivalent of washi.

Boku (Boku) - Familiar youth male version. Rarely used by women, in this case “unfemininity” is emphasized. Used in poetry.

Ore - Not a very polite option. Purely masculine. Like, cool. ^_^

Ore-sama - "Great Self". A rare form, an extreme degree of boasting.

Daiko or Naiko (Daikou/Naikou) - Similar to “ore-sama”, but somewhat less boastful.

Sessha - Very polite form. Typically used by samurai when addressing their masters.

Hishou - “Insignificant.” A very polite form, now practically not used.

Gusei - Similar to hisho, but somewhat less derogatory.

Oira - Polite form. Typically used by monks.

Chin - A special form that only the emperor has the right to use.

Ware - Polite (formal) form, translated as “[I/you/he] myself.” Used when the importance of “I” needs to be particularly expressed. Let's say in spells (“I conjure”). In modern Japanese it is rarely used to mean "I". It is more often used to form a reflexive form, for example, “forgetting about oneself” - “vare in vasurete.”

[Speaker's name or position] - Used by or when communicating with children, usually within the family. Let's say a girl named Atsuko might say "Atsuko is thirsty." Or her older brother, addressing her, may say, “Brother will bring you juice.” There is an element of “lisping” in this, but such treatment is quite acceptable.

See also: Artist presented. If historical figures were hipsters...

Group meaning “We”

Watashi-tachi - Polite option.

Ware-ware - Very polite, formal option.

Bokura - Impolite option.

Touhou - Regular option.

Group with the meaning “You/You”:

Anata - General polite option. It is also common for a wife to address her husband (“dear”).

Anta - Less polite option. Typically used by young people. A slight hint of disrespect.

Otaku - Literally translated as "Your home." A very polite and rare form. Due to the ironic use by Japanese informals in relation to each other, the second meaning was fixed - “feng, crazy.”

Kimi - Polite option, often between friends. Used in poetry.

Kijou - “Mistress”. A very polite form of addressing a lady.

Onushi - “Insignificant.” An outdated form of polite speech.

Omae - Familiar (when addressing an enemy - offensive) option. Usually used by men in relation to a socially younger person (father to daughter, say).

Temae/Temee (Temae/Temee) - Insulting male version. Usually in relation to the enemy. Something like “bastard” or “bastard.”

Honore (Onore) - Insulting option.

Kisama - A very offensive option. Translated with dots. ^_^ Oddly enough, it literally translates as “noble master.”

If you find an error, please select a piece of text and press Ctrl+Enter.