JAPAN.

CONSTITUTION. We, the Japanese people, acting through our duly elected representatives in the Diet, and determined to secure for ourselves and our posterity the fruits of peaceful cooperation with all nations and the blessing of freedom for our entire country, and to prevent the horrors of another war from being caused by the actions of our governments, do declare , that the people are vested with sovereignty, and establish this Constitution.

State government is based on the unshakable trust of the people, its authority comes from the people, its powers are exercised by representatives of the people, and its benefits are enjoyed by the people. This is a principle common to all mankind, and on it is based the present Constitution. We repeal all constitutions, laws and regulations, as well as rescripts that are contrary to this Constitution. Also on topic:

JAPAN

We, the Japanese people, desire eternal peace and are filled with the consciousness of high ideals that determine relations between people; We are determined to ensure our security and existence, relying on the justice and honor of the peace-loving peoples of the world. We want to take an honorable place in the international community, striving to preserve peace and forever destroy tyranny and slavery, oppression and intolerance on the globe. We firmly believe that all peoples of the world have the right to a peaceful life, free from fear and want.

We are convinced that no state should be guided only by its own interests, while ignoring the interests of other states, that the principles of political morality are universal and that adherence to these principles is the duty of all states that maintain their own sovereignty and maintain equal relations with other states.

Also on topic:

JAPANESE

We, the Japanese people, pledge on the honor of our country that, with all our strength, we will achieve these lofty ideals and goals.

CHAPTER I. EMPEROR.

Article 1. The Emperor is a symbol of the state and the unity of the people of Japan, his status is determined by the will of the entire people, to whom sovereignty belongs.

Also on topic:

JAPANESE ART

Article 2. The Imperial throne is dynastic and is inherited in accordance with the Law on the Imperial Family adopted by Parliament.

Article 3. All acts of the Emperor relating to the affairs of the state may not be taken except with the advice and approval of the Cabinet, and the Cabinet shall be responsible for them.

Article 4. The Emperor shall perform only such acts pertaining to the affairs of the state as are provided for in this Constitution, and shall not be vested with powers connected with the government of the state.

The Emperor, in accordance with the law, can entrust someone with the implementation of his actions related to state affairs.

Article 5. If a regency is established in accordance with the Law on the Imperial Family, the Regent shall carry out actions relating to state affairs in the name of the Emperor. In this case, part one of the previous article applies.

Article 6. The Emperor appoints the Prime Minister on the proposal of Parliament.

The Emperor appoints the Chairman of the Supreme Court on the recommendation of the Cabinet.

Article 7. The Emperor, with the advice and approval of the Cabinet, carries out on behalf of the people the following actions relating to state affairs:

1) Publication of amendments to the Constitution, laws, government decrees and international treaties;

2) Convening of Parliament;

3) Dissolution of the House of Representatives;

4) Announcement of general parliamentary elections;

5) Confirmation of the appointments and resignations of government ministers and other statutory public services in accordance with the law, as well as the mandates and credentials of ambassadors and envoys;

6) Confirmation of amnesties and pardons, commutations of sentences, exemptions from execution of sentences and restoration of rights;

7) Presentation of awards;

Confirmation of instruments of ratification and other diplomatic documents provided for by law;

9) Reception of foreign ambassadors and envoys;

10) Dispatch of ceremonies.

Article 8. No property may be transferred to, received by, or donated by the Imperial Family to anyone except in accordance with a resolution of Parliament.

Prerequisites for the adoption, structure and features of the Japanese Constitution

Constitution of Japan (Japanese: 日本國憲法, 日本国憲法, Nihon-koku kempo:/Nippon-koku kempo:

) is the basic law of Japan, which came into force on May 3, 1947. Formally a series of amendments to the Meiji Constitution, it is traditionally considered a separate Constitution.

No amendments were made to the Japanese Constitution after May 3, 1947.

The Constitution establishes the principles of the parliamentary state system, the basic guarantees and rights of citizens. According to the Constitution, the Emperor of Japan is “a symbol of the state and the unity of the people” and performs a purely symbolic function that does not involve any real power; he carries out all his state acts “on the recommendation of the Cabinet” to the point that there is a widespread erroneous point of view according to which the emperor is not the head of state at all

. The text of the Constitution contains 103 articles, combined into 11 chapters.

The Constitution is also called the "Pacifist Constitution" (平和憲法, Heiwa-kenpo:

) because of the main principle - non-entry into war and non-initiation of military conflict (Article Ninth).

Japan is a constitutional parliamentary monarchy. The Emperor of Japan is only a symbol of the nation, his power is reduced to a minimum, he can only represent his country on the world stage. The Japanese Parliament is the highest and only legislative body vested with great powers.

The Government of Japan is formed with the participation of members of Parliament and is responsible to it. Japan is proclaimed a unitary state with broad local autonomy of administrative and territorial units. In terms of the method of amendment, the Japanese Constitution is rigid. Its change is possible only on the initiative of Parliament. To amend it, the consent of 2/3 of the total number of members of each of the two chambers is required. Ratification is carried out either by a referendum or by a new parliament formed after national elections. The method of ratification is determined by Parliament. The approved amendments are immediately promulgated by the Emperor as an integral part of the Constitution. To date, no amendments have been made to the Japanese Constitution.

The Constitution of Japan was developed by the Japanese government with the involvement of American specialists from the occupation forces. The Constitution of Japan came into force on May 3, 1947. It was based on the principles of Anglo-Saxon law, a democratic approach to the processes of regulating social relations. The Japanese Constitution is an unchangeable legal document.

The Japanese Constitution is a short document consisting of 11 chapters and 103 articles. These articles regulate all the basic values of Japan: the status of the Emperor, the legal status of Parliament, the election of both houses, the Cabinet, the rights and duties of the people, and renunciation of war. The activities of the judiciary and local self-government, the distribution of public finances, and the principles of popular sovereignty are also regulated.

The main provisions of the Japanese constitution include anti-militarist activities and the complete refusal to conduct hostilities. According to Art. Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution: “The Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation, as well as the threat or use of armed force as a means of resolving international disputes.” This article of the Constitution limits the constitutional rights of the state to organize the land, naval, and air forces of Japan. The Constitution also prohibits other means of war. In addition, this state cannot increase its military budget above the established level, i.e., no more than 1% of the state budget. In Japan, only one branch of the armed forces is allowed - the Civil Defense Corps. In addition, according to the Constitution in Japan, only civilians have the right to join the government.

The Constitution (Kempo) was prepared after the end of World War II by a group of foreign, mainly American, experts and was adopted by Parliament in October 1946. Entered into force on May 3, 1947. The Japanese Constitution is extremely democratic.

The Japanese Constitution states that Japan forever renounces war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of armed force as a means of resolving international conflicts. Japan cannot have a military force. There are so-called defense forces in the country.

System of government bodies. The Emperor is the head of state. The imperial throne in Japan is inherited only through the male line. In this case, preference is given to the eldest son. According to the Constitution, the Emperor does not have personal power. His status and actions are determined by the will of the people. Competence of the Emperor: the right to appoint the Prime Minister on the proposal of Parliament; the right to appoint the Chief Judge of the Supreme Court on the recommendation of the Cabinet; the right to promulgate amendments to the Constitution, laws, and Cabinet decrees; the right to convene Parliament for a session; the right to dissolve the lower house and announce elections to Parliament and other basic powers of the head of state.

The Japanese Parliament consists of two chambers: the House of Representatives and the House of Councillors. The House of Representatives is elected for a term of 4 years, the House of Councilors is elected for a term of 6 years, with half the membership renewed every 3 years. Sessions of Parliament are held once a year.

If necessary, the Government may decide to convene an extraordinary session. There are permanent and temporary committees under Parliament, including each chamber, before discussing a bill, which must transfer it to a standing committee for consideration.

Among the most important powers of Parliament is control over the activities of the Government and the executive branch. The right of interpellation and parliamentary investigation are used as forms of control.

The Constitution also contains chapters on the Cabinet of Ministers, bicameral Parliament, financial matters, justice and local government. There is no such body as the Constitutional Court in Japan, and any citizen can apply to protect their rights in any court. To adopt amendments to the Constitution, 2/3 votes of the total composition of Parliament are required, followed by approval in a referendum.

CHAPTER II. REFUSAL TO WAR

Article 9. Sincerely striving for international peace based on justice and order, the Japanese people forever renounce war as a means of exercising national sovereignty, as well as the threat or use of armed force as a means of resolving international disputes.

To achieve the goal specified in the previous part, land, sea and air forces, as well as other types of military capabilities, will never again be created. The right of the state to wage war is not recognized.

Constitution of Japan: general characteristics, procedure for amendment

Adopted on November 3, 1946 and entered into force on May 3, 1947, the Japanese Constitution is one of the most stable constitutional documents in the world: not a single amendment has been made to it for more than 50 years. The project was developed at the headquarters of the occupation forces, finalized by the government and adopted by the Parliament elected in 1946. In a certain sense, the unchangeable Constitution is a legal monument to this event.

This is a monarchical constitution, but the rights of the monarch are significantly reduced compared to the previous constitutional act; the provisions relating to the status of the monarch and the Crown give the act its distinctive character.

The Constitution contains a wide list of rights and freedoms, some of them formulated as collective rights.

The Japanese Constitution consists of a preamble (which does not have such a name) and 11 chapters, combining 103 articles.

The preamble contains a number of statements about the pacifist nature of the new state and the peace-loving aspirations of the Japanese people.

Chapter I, "The Emperor," includes articles on the role and significance of the emperor as "a symbol of the state and the unity of the people."

Chapter II consists of one article on the Japanese people's renunciation "in perpetuity" of war, the threat or use of armed force as a means of resolving international disputes.

Chapter III “Rights and Responsibilities of the People” contains articles on human and civil rights, however, formulated in a number of cases in a collectivist spirit as the rights of the people.

Chapter IV “Parliament” is devoted to the procedure for the formation and activities of Parliament, as well as some aspects of the legislative process.

Chapter V "Cabinet" establishes the general principle: the Cabinet exercises executive power, as well as the powers of the Prime Minister, the basis of the relationship between the government and the House of Representatives, and the main powers of the Cabinet.

Chapter VI “Judicial Power” contains provisions on the court system, a ban on the creation of special courts, requirements for candidates for the position of judges, the procedure for the formation of courts and the appointment of judges to positions.

Chapter VII "Finance" includes articles on the state budget, expenditures of the imperial family (as part of the budget) and financial reporting.

Chapter VIII “Local Self-Government” regulates the basics of the legal status of local public authorities.

Chapter IX “Amendments” is devoted to the issues of introducing amendments to this Constitution.

Chapter X “The Supreme Law” contains a description of the Constitution as a legal act, the duty of officials to respect and protect the Constitution.

Chapter XI “Additional Provisions” contains provisions of a transitional nature and a provision on the entry into force of the Constitution.

According to the order of amendments, the Japanese Constitution is rigid. There is a procedure consisting of two stages: at the first stage, Parliament introduces an initiative, and at least 2/3 of the total number of members of both chambers must vote for it, the second stage is the approval of the people. It can be expressed in one of two forms: either in the form of a special referendum, or by a new composition of Parliament after the elections.

The decision on how the second stage will proceed is made by Parliament.

CHAPTER III. RIGHTS AND OBLIGATIONS OF THE PEOPLE

Article 10 The necessary conditions to be a Japanese citizen are determined by law.

Article 11. The people enjoy freely all fundamental human rights. These fundamental human rights guaranteed to the people by this Constitution are granted to present and future generations as inviolable, eternal rights.

Article 12. The freedoms and rights guaranteed to the people by this Constitution shall be maintained by the constant efforts of the people. The people must refrain from any abuse of these freedoms and rights and are responsible for using them solely in the interests of the public good.

Article 13 All people must be respected as individuals. Their right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness should, so far as it does not interfere with the public good, be the supreme concern of legislation and other branches of government.

Article 14 All people are equal before the law and may not be discriminated against in political, economic or social relations on account of race, religion, gender, social status, or origin.

Peerages and other aristocratic institutions are not recognized.

No privileges are conferred upon the conferment of honorary titles, bodies or other awards. Any award is valid only during the lifetime of the person who currently has it or may receive it in the future.

Article 15. The people have the inalienable right to elect state and municipal officials and to remove them from office.

All state and municipal employees are servants of the whole society, and not of any one part of it.

In the elections of state and municipal officials, universal suffrage for adults is guaranteed.

In any elections, the secrecy of voting must not be violated. The voter is not responsible, either publicly or privately, for the choice he makes.

Article 16. Everyone has the right to file a peaceful petition for compensation for damages, for the removal of state and municipal officials, for the introduction, repeal or modification of laws, orders or rules, as well as on other issues; no one shall be subjected to any discrimination for filing such petitions.

Article 17. Everyone may, in accordance with the law, demand compensation from the state or municipalities for damages if the damage was caused to him by the illegal actions of any state or municipal employee.

Article 18 No one shall be held in any form of slavery. Forced labor, other than as punishment for a crime, is prohibited.

Article 19. Freedom of thought and conscience must not be violated.

Article 20 Freedom of religion is guaranteed for everyone. No religious organization should receive any privileges from the state and may not exercise political power.

No one may be forced to participate in any religious act, festival, ceremony or ritual.

The state and its authorities must refrain from conducting religious instruction and any other religious activities.

Article 21. Freedom of assembly and association is guaranteed, as well as freedom of speech, the press and all other forms of expression.

No censorship is allowed; the confidentiality of communications must not be violated.

Article 22. Everyone enjoys freedom of choice and change of residence, as well as choice of profession, as long as this does not violate the public good.

The freedom of everyone to travel abroad and the freedom to renounce their citizenship must not be violated.

Article 23. Freedom of scientific activity is guaranteed.

Article 24 Marriage is based only on the mutual consent of both parties and must be maintained on the basis of mutual cooperation, which is based on the equality of rights of husband and wife.

Laws regarding choice of spouse, property rights of spouses, inheritance, choice of residence, divorce and other matters related to marriage and family should be framed based on individual dignity and fundamental equality of the sexes.

Article 25. Everyone has the right to maintain a minimum standard of healthy and cultural life.

In all spheres of life, the state must make efforts to raise and further develop social welfare, social security, and public health.

Article 26 Everyone has an equal right to education according to their abilities in the manner prescribed by law.

Everyone has a legal obligation to ensure that children in their care receive a general education. Compulsory education is free of charge.

Article 27. Everyone has the right to work and is obliged to work.

Standards for wages, working hours, rest and other working conditions are determined by law.

Exploitation of children is prohibited.

Article 28. The right of workers to organize, as well as the right to collective bargaining and other collective actions is guaranteed.

Article 29. The right of property is inviolable.

Property rights are determined by law so that they do not conflict with the public good.

Private property may be used for the public benefit for fair compensation.

Article 30 The population is obliged to pay taxes in accordance with the law.

Article 31 No one shall be deprived of life or liberty or subjected to any other punishment except in accordance with the procedure established by law.

Article 32 No one may be deprived of the right to have his case examined in court.

Article 33. No one may be detained, except in cases where the detention occurs at the scene of a crime, except on the basis of an order issued by a competent judicial officer, which specifies the crime that is the reason for the detention.

Article 34 No one may be arrested or detained unless he is immediately charged and given the right to legal counsel. Likewise, no one can be detained without due grounds, which, if required, must be immediately communicated in an open court session in the presence of the detainee and his defense attorney.

Article 35. Except as provided in Article 33, the right of everyone to the inviolability of his home, documents and property from invasion, searches and seizures made otherwise than in accordance with an order issued for good cause and containing an indication of the place to be search and items to be seized.

Each search and seizure is carried out pursuant to a separate order issued by a competent judicial officer.

Article 36. The use of torture and cruel punishment by state and municipal employees is strictly prohibited.

Article 37. In all criminal cases, the accused has the right to a speedy and public hearing by an impartial court.

The accused in a criminal case is given full opportunity to interview all witnesses; he has the right to compulsorily summon witnesses at public expense.

Under any circumstances, a defendant in a criminal case may seek the assistance of a qualified defense attorney; in cases where the accused is unable to do this himself, a defense attorney is appointed by the state.

Article 38 No one may be forced to testify against himself.

A confession made under duress, torture or threat, or after an unreasonably long arrest or detention cannot be considered as evidence.

No one can be convicted or punished in cases where the only evidence against him is his own confession.

Article 39 No one can be held criminally liable for an act which was lawful at the time it was committed or for which he was justified. Likewise, no one can be prosecuted twice for the same crime.

Article 40 If acquitted by the court after arrest or detention, anyone may, in accordance with the law, bring a claim against the state for damages.

Shotoku Constitution

(604 AD)

Among the written monuments of Japan of the 7th-8th centuries. n. e. An important place belongs to a group of the first legislative acts: the Shotoku Constitution 1 (604), the Taika Manifesto (646) and the Taiho-Yoro Code of Laws (702-718).

The first Japanese written monument that has survived to this day is the Shotoku Constitution (hereinafter referred to as the Constitution). The significance of this monument is great not only because it is the first legislative document, but also because the Constitution had a great influence on the legislative acts of the Japanese kings, and the ideas contained in it were gradually realized during the formation of the Japanese early feudal state.

Academician N.I. Conrad wrote: “The idea of a new state organization received its first expression in Japan in the form of the “Law of 17 Articles,” published in 604 by Shotoku-Taishi. Actually, it was not a law, but a declaration of new principles of government. The main idea of this declaration is the absolute primacy of the state and its representative - the bearer of supreme power." 2 .

In Japanese historiography, the monument in question is called the “Seventeen-Article Constitution” or “Constitution of the Heir Shotoku”, because its author is traditionally considered Prince Shotoku.

Japanese legal historian Sogabe Shizuo o 3.

Prince Shotoku was an active preacher of Buddhism in Japan (during his regency, Buddhism was declared the state religion of Japan). Therefore, the Constitution, which was based on Confucian ideas about a centralized state headed by a wise ruler, has a strong influence of Buddhism.

The Constitution is the first declaration of the kings of Yamato (Japan), who declared their rights to supreme power in the country. To this end [128]

kings of Yamato at the end of the 6th century. called for help from the Buddhist Church with its well-organized and centralized apparatus.

The Constitution also served the same task in terms of ideological justification for the political aspirations of the Yamato kings.

The main ideas of the Constitution received more realistic expression in the Taika Manifesto published half a century later (646).

Neither the autograph nor individual copies of the Constitution have survived, although it is known that at the end of the 12th century. there was some kind of list of it, since during this period the Constitution was printed by woodcut 4.

In the Nihongi (“Annals of Japan”) 5 , under the date 12th year of Suiko [604], 4th moon, 3rd day, it is written: “The heir to the throne [Shotoku] personally compiled for the first time a “Constitution of 17 Articles”” 6 .

Thus, the time of creation of the Constitution was established - 604 AD. e. 7 . In structure, the Constitution actually consisted of 17 articles, and in content, it was an instruction from the ruler of Japan of the late 6th - early 7th centuries, taught to officials, starting with court dignitaries and ending with provincial officials, i.e. an instruction to the entire emerging bureaucracy of that time.

The sources that served as the basis for the Constitution were most likely Chinese documents and writings from previous centuries. However, Japanese historians, despite the similarity of the wording of the Constitution and some ancient Chinese philosophical works (Lunyu, Liji, Guanzi, Laozi, etc.; see: NCT. T. 68, p. 181, note 13, p. 182, note 22 , p. 183, note 15, etc.), could not establish any single source that served as the basis for the Constitution, although Confucian influence is clearly visible in it. Perhaps this is explained by the fact that by the 7th century. Confucianism, which became the official ideology of the Han and subsequent periods in China, has already absorbed elements of other teachings (mainly Legalism and Taoism) 8 .

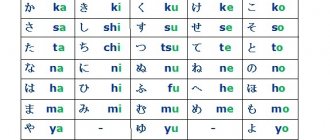

The autograph of the Constitution was undoubtedly written in Chinese, for at the beginning of the 7th century. Japan did not have its own written language. The autograph has not survived, and copies of the Nihongi copy date back no earlier than the 13th-14th centuries. and are already written in one of the writing styles of the Japanese language - kambun

, which is a Chinese wenyan transformed over several centuries.

However, in a number of Japanese publications of the Constitution (as part of the Nihongi), in parallel with the text in Kambun'e

Wabun'e

is placed (*** - reconstructed ancient Japanese language; see, for example: NCT. T. 68, pp. 180, 182 , 184, 186). Problems of reconstruction of the Old Japanese language are subject to special consideration.

We translated the Constitution from the Kambun text.

Since the Constitution is fully included in the Nihongi (see: NKT. T. 68, pp. 181-187),

[129]

it is published (as amended by the Nihongi) in numerous series on the history of Japan

9 .

Mention of it is contained in the studies of Japanese historians on the ancient period, for example, in Sakamoto Taro - “Ancient Period”, Part I, “Complete History of Japan”, vol. 2 10 , in the “Great Japanese Historical Encyclopedia” 11 , etc.

Among the translations of the Constitution into European languages, it should be noted: G. Aston. Nihongi. II. L., 1896, p. 128-132 (hereinafter referred to as AST); K. Florenz. Japanische Annalen. Bd. XXII. Nihongi. Tokyo, 1903, S. 13-20 (hereinafter referred to as FLO); The Teaching of Buddha (The Buddhist Bible). Tokyo, 1966, p. 230-236; Nakamura Hajime. A History of the Development of Japanese Thought. Vol. I. Tokyo, 1967, p. 5-13 (incomplete translation - seven articles omitted; hereinafter - NAC).

The following translations of the Constitution are known in Russian: N.I. Conrad. Selected works. Story. M., 1974, p. 68-69; Only five articles (3, 4, 8, 12, 16) have been fully translated, and twelve articles have been summarized. Translation by N.A. Iofan “The Law of 17 Articles” was published in the “Anthology on the History of the Middle Ages” (Moscow, 1961, pp. 129-132), this is an incomplete and inaccurate translation from English according to V. Aston (see above), in it missing in Article 5 - five, in Article 9 - one and in Article 14 - three points.

In the book by Ya.B. Radul-Zatulovsky “Confucianism and its spread in Japan” (Moscow, 1947) provides a translation of only the third article of the Constitution (p. 208). However, since the translation was not made from the original text of the kambun,

and from the reconstructed ancient Japanese

wabun text,

placed in a footnote on the same page (without indicating the source), then we do not consider it.

The general content of the Constitution is briefly outlined in the book by M. V. Vorobyov “Ancient Japan” (M., 1958). There are references to the Constitution in other historical works, for example in “The History of Foreign Asian Countries in the Middle Ages” (M., 1970).

There are no monographic studies of the Constitution in European languages.

Below is the first complete translation into Russian of the Shotoku Constitution. 12.

Shotoku Constitution

[preamble]

12th year, summer, 4th moon, tiger day 13.

The heir to the throne 14 personally and for the first time drew up 15 of the 17 articles of the constitution.

1 article. Value agreement and base [the spirit of] non-resistance 16.

People always have groups 17 , but there are few wise people 18 . [130]

Therefore, some do not obey either the sovereign or their father, and are also at enmity with their neighbors.

However, with agreement at the top and friendliness at the bottom, with consistency in discussions, things will go in a natural order 19 . And then everything will come true.

Article 2. Zealously honor the three treasures; these three treasures are Buddha, Dharma and Sangha 20.

[They] are the last refuge of [creatures] of four births 21 and the highest faith in all countries 22 .

All people, all worlds revere this dharma. Few people are very bad; if they are taught well, they will obey. They can only be corrected with the help of these three treasures.

Article 3. Respectfully accepting the sovereign's decrees, be sure to comply with [them].

The sovereign is the sky, the vassals are the earth. The sky covers [the earth], and the earth supports the sky.

[When this is so, then] the four seasons follow their course and everything in nature goes normally 23.

When the earth desires to cover the sky, [this] will lead to destruction.

That is why, when the sovereign speaks, the vassals listen; when the superiors act, the inferiors obey.

Therefore, while respectfully accepting the sovereign's decrees, be sure to comply with [them]. If [they] are not respectfully observed, then naturally [everything] will be destroyed.

Article 4. Dignitaries and officials! Make ritual the basis [of your activities] 24.

The basis of governing the people certainly lies in [observing] ritual. If the higher ones do not observe the ritual, then there is no order among the lower ones; if the lower ones do not observe the ritual, then crimes are sure to arise.

Therefore, if dignitaries and officials follow the ritual, then everything goes fine. If the common people observe the ritual, then the state is governed naturally.

Article 5. Get rid of gluttony, give up greed and deal with complaints fairly.

After all, complaints from ordinary people in one day [accumulate] up to a thousand cases. If there are so many complaints even in one day, how many of them will accumulate in a year?

Lately, it has become a custom for complaint handlers to take [personal] advantage from it and listen to allegations after receiving a bribe.

That is why the complaint of a wealthy person is like a stone thrown into water, and the complaint of a poor person is like water poured on a stone. 25.

Therefore, the poor people know no refuge.

This is precisely where the shortcomings of the [true] path of our vassals lie.

Article 6. Punishing evil and encouraging good is a good ancient rule; Therefore, do not hide the good of people, and when you notice evil, be sure to correct it.

Flatterers and deceivers are a sharp weapon for undermining the state; [they] are a sharp-pointed sword, slaying [their] people.

Sycophants also willingly speak to superiors about the mistakes of inferiors, and in front of inferiors they slander about the mistakes of superiors.

Such people are always unfaithful to the sovereign and unmerciful to the people, and this is the source of great unrest. [131]

Article 7. Each person should have his own responsibilities and [the affairs of] management should not be mixed 26.

When an intelligent person is appointed to a post, praise is heard; when an unprincipled person occupies office, disorder abounds.

There are few people in the world with natural knowledge; wisdom is the product of deep reflection.

There are no big or small things; all matters will definitely be settled if capable people are taken to positions.

And in time there is no urgent and non-urgent; with smart people [in positions] all [things] will naturally work out.

Thus, the state will be eternal and the country 27 will be safe.

Therefore, in ancient times, wise sovereigns looked for capable people for posts, and did not look for posts for people.

Article 8. Dignitaries and officials! Come to court early and leave late. State affairs do not allow for negligence. [Even] for the whole day [they] are difficult to complete. Therefore, if you come to the court late, you will not be able to deal with urgent matters. If you leave early, you will certainly not complete your work.

Article 9. Trust is the basis of justice; There must be trust in every business.

Good and evil, success and failure are certainly based on trust.

If dignitaries and vassals trust each other, then any business will come true. If dignitaries and vassals do not trust each other, then everything will collapse.

Article 10. Let go of anger, let go of resentment, and don't get angry at others for not being like you.

Every person has a heart. Each heart has its own inclinations.

If he's right, then I'm wrong. If I'm right, then he's wrong. I am not necessarily a wise man, and he is not necessarily a fool. We are both just ordinary people.

Who can accurately determine the measure of right and wrong?

We are both smart and stupid together, like a ring without ends. Therefore, although he is angry with me, I, on the contrary, must be afraid of making a mistake myself.

Although I may be the only one who is right, I must follow everyone and act the same [with them].

Article 11. Evaluate merits and demerits fairly; Be sure to reward and punish accordingly.

It happens that rewards [are given] not according to merit, and punishments are not due to fault.

Dignitaries in charge of state affairs! Identify those who deserve both reward and punishment.

Article 12. Royal controllers of provinces and governors of provinces! Do not impose [double] taxes on the common people.

There are no two sovereigns in the country; The people do not have two masters. The sovereign is the master of the people of the entire country.

The officials appointed [by him] are all vassals of the sovereign. Why do [they], along with the treasury, dare to [illegally] impose [taxes] on the common people?

Article 13. All appointed officials must perform [their] official duties equally [well].

You can only skip work due to illness or work assignments. However, when you are able to fulfill your duty, then act as before, in [the spirit of] agreement 28. [132]

[Officials], do not delay state affairs under the pretext that [they] do not apply to you.

Article 14. Dignitaries and vassals! Don't be envious. If we envy others, then others envy us. The troubles of envy have no limits.

For this reason, if [someone] surpasses [us] in intelligence, then [we] do not rejoice; if [someone] surpasses [us] in abilities, then [we] envy him. Therefore, you meet a smart person [once] every five hundred years, [and] it is difficult to find one wise man [once] every thousand years 29 . However, how will a country be governed without smart people and sages?

Article 15. To turn away from the personal and towards the state is the [true] path of a vassal.

If a person is possessed by the personal, then [he] is necessarily possessed by anger. If a person is overcome by anger, then [he] will definitely have disagreements with others. In case of disagreement, the personal harms the state.

When anger arises, it goes against order and harms the laws.

Therefore, as stated in the first article, the mutual agreement of the higher and lower is the spirit of this [article].

Article 16. To employ the people [in labor service] 30 at the appropriate time of the year is a good ancient rule; Therefore, people should use it during the winter months when they have free time. From spring to autumn, during the season for cultivating fields and mulberries, people cannot be used.

If you don’t cultivate the fields, then what is there? If you don’t process mulberries, then what should you wear? 31

Article 17. Important matters cannot be decided alone; They must be discussed with everyone.

With small things it's easy; It is not necessary to [discuss them] with everyone.

If you consider important matters [individually], then doubts about the presence of an error are permissible, but in agreement with everyone, [your] judgments can receive reliable justification 32.

K. A. Popov

Notes

It seems to us that the Constitution is mainly written in one of the styles of Kambun *** ( Shirokubun;

from China Xiluwen; lit., “style of fours and sixes”), which is based on combinations of four or six hieroglyphs. This style is built on parallelism (see: Shimura Izuru. Kojien. Tokyo, 1955, p. 1137; hereinafter referred to as SIM). For example, “top-bottom” (1st art.), “heaven-earth” (3rd art.), etc.

The text of the monument contains some hieroglyphs that serve official functions; for example, *** - paragraph mark, *** - particle of emotional emphasis of the subsequent member of the sentence, *** - connective between two subordinate clauses, case indicators: *** - dative, *** - object, *** - locative and etc.

Often one word is written in different hieroglyphs, for example “more” - *** and *** - mata

(see: NKT. T. 68, p. 181, etc.);

“namely” - ***, *** - sunavati

(see: NCT. T. 68, pp. 181, 183);

“required” - ***, *** - kanarazu

(NKT. T. 68, p. 181, 183), etc.

Understanding that a hieroglyph is only a conventional written sign, and not a word (as is customary in foreign Far Eastern linguistics), in the future, for brevity (i.e., instead of “the meaning of the word written with such and such a hieroglyph”, or “translation of the word , designated by such and such a hieroglyph"), we will use phrases: “translation of such and such a hieroglyph,” “the meaning of such and such a hieroglyph.”

Comments

1. Shotoku —

posthumous Buddhist name of a Japanese politician (years of life 574-622) - regent under Queen Suiko (years of reign 592-628); *** - heir.

2. N. I. Konrad.

Selected works. Story. M., 1974, p. 374 (hereinafter referred to as CON).

3. Sogabe Shizuo.

Nitchu ritsuryoron (Essay on the ancient law of Japan and China). Tokyo, 1963, p. 149.

4. O. P. Petrova, V. N. Goreglyad.

Description of Japanese manuscripts, woodcuts and early printed books. Vol. IM, 1963, p. 10.

5. Nihongi is the official history of Japan, the editing of which was completed in 720. Compiled by Toneri (677-735) and O no Yasumaro (?-723). The authenticity of Nihonga as a monument is beyond doubt.

6. Nihon koten bungaku taikei. (Japanese Classical Literature. Large Series). T. 68. Nihongi. Tokyo, 1965, p. 181 (hereinafter referred to as NKT).

7. See also: Nihonshi jiten (Japanese Historical Dictionary). Kyoto, 1957, p. 244.

8 . See for example: L. S. Vasiliev.

Cults, religions, traditions in China.

M., 1970, p. 177-185; F. S. Bykov.

The doctrine of primary elements in the worldview of Dong Zhong-shi. China. Japan. M., 1961.

9. Shintei joho kokushi taikei (History of Japan, revised and expanded large series). T. 2. Tokyo, 1951; Shin-nihonshi taikei (New Great Series of Japanese History). T. 2. Tokyo, 1955; Nihon rekishi (History of Japan). T. 2. Tokyo, 1960, etc.

10. Sakamoto Taro.

Kodai Nihon Zenshi. Tokyo, 1956.

11. Nihon rekishi dai jiten. T. 7. Tokyo, 1960, etc.

12. The translation was made based on the Japanese publication of the critical text of the monument in the multi-volume book “Japanese Classical Literature. Big series." Edited and with comments by major Japanese philologists: Takagi Ichinosuke, Nishio Minoru, Hisamatsu Senichi, Aso Isoji and Tokieda Motoki. (10th edition). T. 68. Tokyo, 1974, p. 181, 183, 185, 187.

13. "12th year, summer, 4th moon, tiger day." There are several versions about the date of publication of the Constitution. We accepted the version of the Nihongi commentators (see: NCT. T. 68, p. 180, note 10, 11); this same version is adhered to by V. Aston (II. 128) and K. Florenc (p. 13).

The 12th year of the reign of Queen Suiko corresponds to the year 604 of the European calendar; “summer” - in Nihongi, after a year of chronicle, the season is always recorded; “4th Moon” - in Yamato (Japan) in the 7th century. the lunar calendar was used, borrowed from China in the 6th century. n. e.; "Tiger Day" corresponds to the third day of the month. In this monument, the Chinese method of counting by sixty cyclic signs is used to designate days (for details, see: D. Pozdneev. Hieroglyphic Dictionary. Tokyo, 1907, p. 1082, hereinafter - POZ; Chinese-Russian Dictionary edited by I.M. Oshanin M., 1955, appendix, p. 40, hereinafter - OSH).

14. Prince Shotoku was called “heir to the throne” in the Constitution. The word kotaisi in the general meaning of “heir to the throne” has survived to the present day.

15. “...drew up a constitution...”; *** Nihongi commentators (famous Japanese historians and philologists Sakamoto Taro, Ienaga Saburo, Inoue Michiyasu and Ono Susumu) believe that the binomial *** was borrowed by the drafters of the Constitution from the Chinese historical work “Guo Yu”, where in the chapter “Jingyu” ( Speeches of the kingdoms, 3rd century BC) these hieroglyphs were used for the first time (NKT. T. 68, p. 180, note 12).

N. I. Conrad translated *** - “law” (KON, p. 68), K. Florenz - “Verordnung” (FLO, p. 13), V. Aston - “Laws” (ACT, II, p. 128), X. Nakamura - “Constitution” (Nak, I, p. 3); modern Japanese - kempo.

In translation, we use the term “constitution”, fully aware that this is modernization.

16. “Value agreement and base [the spirit of] non-resistance” ***.

We present the full text of the first sentence of Article 1 in order to emphasize that here and in what follows the verb - predicate is translated in the imperative mood, although the corresponding formant is absent in the text itself. This is explained by the fact that the Constitution is an instruction, therefore it is necessary to translate it in the imperative or desirable mood. Other translators of the Constitution also understood the mood of the final verb - predicate, although this was specified only by Nihongi commentators: “If you look at all 17 articles of the Constitution, then [it is clear that] each article certainly contains the meaning of command (***), t .e. has an imperative form like seyo, subeshi;

so in this article, when reading it according to

kun'u

(Japanese reading of the hieroglyph ***), we put: “

...wo tatoshi to sayo... mune to sayo

"" (NKT. T. 68, p. 181, note 13) .

In W. Aston: “Harmony is to be valued...” (ACT, II, p. 129).

In K. Florenz: “Einigkeit und Harmonie sind wertvoll” (FLO, p. 14).

“...agreement...non-resistance”... *** ... ***, although it seemed that there should be a pair of *** ... ***, for *** (“non-resistance: non-resistance”) is borrowed from Buddhist terminology. V. Aston *** translated: “...avoidance of wanted opposition” (ACT, II, p. 129); in K. Florenz: “Gehorsam ist das Unerlasslichste” (FLO, p. 14).

17 . “People always have groups...” ***. In this sentence, *** and *** are not interpreted uniformly; although in V. Aston and K. Florenz this hieroglyph is understood as meaning “everything” (all and alle, respectively), but in the kambun

it often denotes the word “always”, which is used in our translation.

There are several versions regarding which word is written with the hieroglyph ***. Nihongi commentators read his tamura

and added a reference to “Zuo zhuan” and “Han feizi”, ***. A commentary on “Chunqiu” (one of the books of the Confucian Pentateuch) was compiled by Zuo Qiumin (3rd century BC). *** - the name of the legalist philosopher and the title of his work where this word appears (IKT. T. 68, p. 181, note 14). For V. Aston it is “...class feeling” (ACT, II, p. 129), which seems to us to be modernization, for K. Florenz it is “...ihre Sonderinteressen” (FLO, p. 14), which in our opinion is closer to the main point of this article; in X. Nakamura - “...partisanship...” (NAK, G, p. 5), which has a specific connotation. We have accepted the interpretation of the Nihongi commentators, i.e. *** as a “group of like-minded people” (modern “political party”).

18. “...and there are few wise people” ***; In this sentence, some discrepancies are caused by the translation of the binomial ***.

In V. Aston - “...who are intelligent” (ACT, II, p. 129); in K. Florenz - “...Einsichtige unter ihnen” (FLO, p. 15); in X. Nakamura - “...persons are really enlightened” (HAK, I, p. 5); we accepted one of the meanings - *** (satoru hito;

see: NKT. T. 68, p. 180).

19. “...things will go in a natural order” ***; this quadrip is understood in different ways: V. Aston - “...right views of things spontaneously gain acceptance” (ACT, II, p. 129); somewhat differently in K. Florenz - “...so schreiten die Dinge von selbst fort” (FLO, p. 15); another option is by X. Nakamura - “...and things become harmonious with the truth” (HAK, I, p. 5); It seems to us that our translation is closer to the original text.

20. Dharma is the sacred law; sangha - monastic brotherhood.

21. Those. all living beings that were born through four types of birth: from the egg (chick), from the womb (baby), from dampness (mold) and transformation (from one to another, for example from a caterpillar to a butterfly).

22 . In sentence *** the last binomial is translated differently: V. Aston - “...the supreme objects of faith” (ACT, II, p. 129); K. Florenc - “...die Urprinzipien...” (FLO, p. 15); in -Nihongi - “... kivame no mune”;

our version of the translation is close to the version of V. Aston (see above).

23 . “...and everything in nature goes fine” (***). There are several versions of the translation of this sentence: N. Conrad - “... the movement of all forces is unfolding” (KON, p. 68); V. Aston - “...the powers of nature obtain their efficacy” (ACT, II, p. 129), i.e. close to the understanding of N. Conrad; K. Florenz - “...die Zehntausend Geister gehen ohne Beschrankung” (FLO, p. 16); this is an almost literal, but, as it seems to us, not entirely accurate translation; in addition, the addition of K. Florenz, which is absent in the original text, is unclear (see in square brackets); X. Nakamura - “...we see the world ruled in perfect order” (HAK, I, p. 12); in Nihongi - “... yorōzu no shirusi kayofu koto wo u”

(NKT. T. 68, p. 182) (literally “10 thousand elements [of nature] can circulate”). The interpretation of *** (Japanese - ki, Chinese - qi) in ancient philosophy is complex. This can mean: beginning (spiritual, material); material particle; spirit; Power of nature; element of nature, etc. The choice of specific meaning depended on the context.

24. “...make the basis... a ritual” (***). The word is ray whale. - (whether) polysemantic; in the “Big Japanese-Russian Dictionary”: rey - 1. Bow, greeting; 2. Politeness, rules of politeness, courtesy, etiquette; 3. Ritual, ceremony (vol. I, p. 797); from D. Pozdneev: ray - ceremony, politeness, ritual, gratitude (POZ, p. 492); in the Japanese explanatory dictionary “Kojien”: rei - etiquette, rules of decency (reigi) (SIM, p. 2210); in the “Chinese-Russian Dictionary”: *** li - 1. Decency, restraint, culture; 2. Etiquette, ceremony, rite, ritual (OS, p. 75).

In Nihongi (***) read: iyabi

(veneration, respect, ceremony) (see: NCT. T. 68, p. 182); V. Aston: “The Chinese li, decorum, courtesy, proper behavior, ceremony, gentlemenly conduct as we should say” (ACT, II, p. 129); K. Florenz: “Die gute Sitte” li...” (FLO, p. 16); H. Conrad: “...the law (is)...” (CON, p. 68); L. Perelomov: “...li is a system of [Confucian] moral and ethical principles, norms of behavior that all residents of the Celestial Empire must observe” (L. S. Perelomov. Book of the ruler of the Shan region. M., 1968, p. 61).

In this article we conventionally refer to *** as “ritual”; the content of this concept changed in the process of historical development of social thought in both China and Japan.

25. This saying was borrowed, as commentators point out (see: NCT. T. 68, p. 183, note 11, 12; K. Florenz, p. 16, note 4), from an anthology of Chinese literature *** (Wen Xuan ; compiled around 530 AD by a group of literati led by Xiao Tong). Its meaning: the complaint of the rich easily passes through the authorities (like a stone into water), and the complaint of the poor is ineffective (like splashes of water on a stone).

26 . “... [the affairs of] management should not be mixed” (***). The meaning of this quadrinome is unclear, therefore its translation is not uniform; V. Aston: “...let not the spheres of duty be confused” (ACT, II, p. 130); the same with X. Nakamura (NAK, I, p. 10), but with K. Florenz: “Thut euer Bestes, das ihr es nicht verwirrt!” (FLO, p. 17), which differs from W. Aston’s translation; in Nihongi: “Tsukasadoru koto midarezaru beshi

”(literally “management should not be mixed”; NCT. T. 68, p. 182).

27 . "…a country…"; in the text ***; in Nihongi read: kuni

(NKT. T. 68, p. 183), although V. Aston: “...the temples of the earth and of grain” (ACT, II, p. 130);

in X. Nakamura: “...the realm” (NAK, I, p. 10); we consider *** to be a binomial denoting one word and therefore adopted the commentators' version of Nihongi (kuni

) - “country”.

28. “... act as before, in [the spirit of] agreement” (***). Here the verb *** is used in the old meaning of “act”, “lead”.

29. “That’s why you meet a smart person [once] every five hundred years, [but] it’s hard to find one wise man [once] every thousand years” (***). We assume that the binomials are *** and ***. are used metaphorically and mean: “rarely” and “very rarely.” This sentence is unclear in meaning; it is borrowed from Chinese works (in Nihongi there are references to “Han Feizi” and “Wen Xuan”, see: NCT. T. 68, p. 185, note 12, 13), therefore the translations are not the same; V. Aston: “Therefore it is not until after a lapse of five hundred years that we at last meet with a wise man and even in a thousand years we hardly obtain one sage” (ACT, II, p. 132); K. Florenz: “Obgleich ihr einem klugen Mann alle fiinfhundert Jahre antreffen konnt, so werdet ihr doch kaum in tausend Jahren einen wirklichen Weisen finden” (FLO, p. 19). The translations by W. Aston and K. Florenz are lengthy, and they introduce personal pronouns that are not in the original (see above).

30. “Use the people [for labor service]...”; We have introduced an explanation in parentheses because it follows from the meaning of the entire 16th article.

31 . The last two sentences of the Constitution *** are impersonal, therefore they allow three translation options: the first - by W. Aston and N. Conrad: “...what will they

(our italics -

K.P.

) have to eat?.. what will they do for clothing?”

(ACT, II, p. 132) and “... what they

(our italics -

K.P.

) sow (in the text *** - “eat, eat”), ... what will

they

(our italics. -

K.P.

) will dress” (KON, p. 69), i.e.

talks about peasants; the second option - K. Florenza: “Was sollen wir

(our italics -

K.P.

) essen... und wie sollen wir uns kleiden...” (FLO, p. 20), i.e. it directly refers to the ruling elite; the third option is ours (see Article 16, last paragraph); there are no comments in Nihongi; We translated the text in an impersonal sentence, although we admit that the Aston-Conrad version might be more suitable.

32. “...[your] judgments can be reliably justified” (***). The meaning of this expression is not entirely clear. N. Conrad did not translate Article 17, but wrote: “Article 17 introduces the principle of a kind of collegiality of the most important decisions” (CON, p. 69). However, it seems to us that Article 17 does not speak about collegial decisions, but only about the desirability of meetings on important matters.

In K. Florenz: “Dann wird es etwas Vernunftiges werden” (FLO, p. 20); in W. Aston: “...so as to arrive at the right conclusion” (ACT, II, p. 133); in Nihongi: “... koto sunawati kotowari wo

"(NKT. T. 68, p. 186) (literally: “words receive reasons”); we have accepted the Nihongi commentators' version.

(translated by K. A. Popov) Text reproduced from the publication: Constitution of Shotoku (604 AD) // Peoples of Asia and Africa, No. 1. 1980

© text - Popov K. A. 1980 © network version - Thietmar . 2011 © OCR - Ivanov A. 2011 © design - Voitekhovich A. 2001 © Peoples of Asia and Africa. 1980

CHAPTER IV. PARLIAMENT

Article 41. Parliament is the highest body of state power and the only legislative body of the state.

Article 42. Parliament consists of two Chambers: the House of Representatives and the House of Councillors.

Article 43 Both Houses shall be composed of elected members representing the whole people.

The number of members of each House is established by law.

Article 44. The qualifications of the members of both Houses, as well as the qualifications of their voters, are determined by law. However, there must be no discrimination based on race, religion, gender, social status, origin, education, property or income.

Article 45. The term of office of members of the House of Representatives is four years. However, their powers terminate before the expiration of their full term in the event of the dissolution of the House of Representatives.

Article 46. The term of office of members of the House of Councilors is six years, with half of the members of the House being re-elected every three years.

Article 47 The electoral districts, method of voting and other matters relating to the election of members of both Houses shall be determined by law.

Article 48 No one can be a member of both Houses at the same time.

Article 49. The members of both Houses receive annually, in accordance with the law, a certain diet from the state treasury.

Article 50. Members of both Houses, except in cases provided for by law, cannot be detained during the session of Parliament; Members of Parliament detained before the opening of the session must, at the request of the relevant Chamber, be released from imprisonment for the duration of the session.

Article 51. Members of both Houses are not responsible outside the House in connection with their speeches, statements and votes in the House.

Article 52. Regular sessions of Parliament are convened once a year.

Article 53. The Cabinet may decide to convene extraordinary sessions of Parliament. The Cabinet must decide to convene Parliament if so requested by at least one-fourth of the total number of members of one of the Houses.

Article 54 If the House of Representatives is dissolved, then within forty days from the date of its dissolution, general elections to the House of Representatives must be held, and within thirty days from the date of the elections, Parliament must be convened.

When the House of Representatives is dissolved, the House of Councilors also ceases to meet. However, the Cabinet may call an emergency meeting of the House of Councilors if this is absolutely necessary in the interests of the country.

The measures taken at the emergency meeting mentioned in the previous part are temporary and become invalid if they are not approved by the House of Representatives within ten days of the opening of the next session of Parliament.

Article 55 Each House shall resolve disputes relating to the mandate of its members. However, in order to deprive someone of parliamentary powers, a resolution to this effect must be adopted by a majority of at least two-thirds of the votes of the members present.

Article 56. Each Chamber may open a meeting and make decisions only if at least one third of the total number of its members is present at the meeting.

Except as otherwise expressly provided in this Constitution, all matters in each House shall be decided by a majority vote of the members present; In case of equality of votes, the vote of the presiding officer is decisive.

Article 57. Meetings of each Chamber are open. However, closed meetings may be held if a resolution to that effect is passed by a majority of at least two-thirds of the members present.

Each House keeps minutes of its meetings. These minutes must be published and distributed for public review, with the exception of those minutes of closed meetings that are considered especially secret.

At the request of at least one-fifth of the members present, each member's vote on any matter shall be recorded in the minutes.

Article 58 Each House shall elect a President and other officers.

Each House establishes its own rules of business, procedure and internal discipline and may impose penalties on its members for conduct that violates discipline. However, in order to expel a member of the House from its membership, a resolution to this effect must be adopted by a majority of at least two-thirds of the votes of the members present.

Article 59. A bill, except in cases specifically provided for by the Constitution, becomes a law after its adoption by both Houses.

A bill passed by the House of Representatives, on which the House of Councilors has decided differently from the decision of the House of Representatives, becomes law after its second adoption by a majority of at least two-thirds of the members of the House of Representatives present.

The provision of the previous paragraph does not prevent the House of Representatives from requiring, in accordance with the law, the convening of a conciliation meeting of both Houses.

If the House of Councilors does not take a final decision on a bill passed by the House of Representatives within sixty days, excluding the adjournment of Parliament, after receiving it, the House of Representatives may consider this to be a rejection of the bill by the House of Councilors.

Article 60 The budget must first be submitted to the House of Representatives.

If the House of Councilors has adopted a decision on the budget that is different from the decision of the House of Representatives, and if agreement has not been reached through the conciliation meeting of both Houses provided for by law, or if the House of Councilors has not made a final decision within thirty days, excluding the time of recess in the work of Parliament, after Once the budget has been passed by the House of Representatives, the decision of the House of Representatives becomes a decision of Parliament.

Article 61 The second part of the previous article applies accordingly to the approval of Parliament necessary for the conclusion of international treaties.

Article 62 Each House may conduct inquiries into matters of government and may in doing so require the attendance and testimony of witnesses and the production of documents.

Article 63. The Prime Minister and other ministers of state, whether members or non-members of either House, may at any time attend meetings of either House to speak on bills. They must also be present at meetings if their presence is required to provide answers and clarifications.

Article 64. Parliament constitutes a court from among the members of both Houses to consider, by way of impeachment, the cases of those judges against whom proceedings for removal from office have been initiated.

Matters relating to impeachment trials are governed by law.

Chapter III. Imperial Diet.

Article XXXIII. The Imperial Diet consists of two chambers - the Chamber of Peers and the Chamber of Deputies.

Article XXXIV. The House of Peers, according to the decree on the House of Peers, should consist of members of the imperial family, representatives of the nobility and persons elevated to this rank by the Emperor.

Article XXXV. The Chamber of Deputies shall consist of members elected by the people, in accordance with the provisions of the electoral law.

Article XXXVI. No one can be a member of both houses at the same time.

Article XXXVII. Every law requires the approval of the Imperial Diet.

Article XXXVIII. Both chambers vote on bills submitted to them by the government, and can also introduce bills themselves.

Article XLI. The Imperial Diet must be convened annually.

Article XLII. The session of the Imperial Diet should last three months. If necessary, the session may be continued by imperial order.

Article XLVI. No debate or voting can begin in any of the chambers of the Imperial Diet unless at least a third of the total number of members is present.

Article XLVII. Issues are resolved in the general chambers by an absolute majority of votes. In case of equality of votes, the casting vote belongs to the chairman.

Article XLVIII. The sessions of both chambers take place in public. However, at the request of the government or by decision of the chamber, meetings may be closed.

Article LII. No member of each House can be held responsible outside of it for the judgments he makes in the House or for the casting of his vote. But if a member of the House makes known his opinions by public speeches, by printed or written documents, or by the like means, he will be liable under the general laws.

Article LIII. During the session, members of both houses are free from detention.

Article LIV. Ministers and government delegates may be present and vote in each House at all times.

CHAPTER V. OFFICE

Article 65. Executive power is exercised by the Cabinet.

Article 66 The Cabinet, in accordance with the law, consists of the Prime Minister, who heads it, and other government ministers.

The Prime Minister and other ministers of state must be civilians.

The Cabinet, when exercising executive power, is collectively responsible to Parliament.

Article 67. The Prime Minister is nominated by a resolution of Parliament from among the members of Parliament. This nomination must precede all other business of Parliament.

If the House of Representatives and the House of Councilors have adopted different resolutions on the nomination, and if agreement has not been reached through the conciliation meeting of both Houses provided for by law, or if the House of Councilors has not made a decision on the nomination within ten days, excluding the time of recess of Parliament, thereafter Once the House of Representatives has made such a nomination, the decision of the House of Representatives becomes a decision of Parliament.

Article 68 The Prime Minister appoints ministers of state; however, the majority of ministers must be elected from among the members of Parliament.

The Prime Minister has the discretion to remove government ministers from office.

Article 69 If the House of Representatives passes the draft resolution of no confidence or rejects the draft resolution of confidence, the Cabinet shall resign as a whole unless the House of Representatives is dissolved within ten days.

Article 70 If the office of the Prime Minister becomes vacant or if the first session of Parliament is convened after the general election of members of the House of Representatives, the Cabinet shall resign as a whole.

Article 71 In the cases mentioned in the two previous articles, the Cabinet continues to perform its functions until a new Prime Minister is appointed.

Article 72. The Prime Minister, as a representative of the Cabinet, introduces bills to Parliament, reports to Parliament on the general state of government affairs and foreign relations, and also exercises leadership and control over various branches of government.

Article 73. The Cabinet performs, along with other general management functions, the following duties:

1) Conscientious implementation of laws; general conduct of government affairs;

2) Management of foreign policy;

3) Conclusion of international treaties; the prior or subsequent approval of Parliament is required;

4) Organization and management of the civil service in accordance with the norms established by law;

5) Drawing up a budget and submitting it to Parliament;

6) Issuance of government decrees in order to implement the provisions of this Constitution and laws; however, government decrees cannot contain provisions providing for punishment and punishment, except with the permission of the relevant law;

7) Making decisions on amnesties, pardons, commutations of sentences, exemptions from execution of sentences and restoration of rights.

Article 74 All laws and government decrees must be signed by the competent ministers of state and countersigned by the Prime Minister.

Article 75. Ministers of state while occupying their positions cannot be brought to justice without the consent of the Prime Minister. However, this does not affect the right to prosecute.

Constitution of Japan 1947: general characteristics.

⇐ PreviousPage 10 of 10

The preparation of the constitutional text was carried out by the Japanese government with the involvement of specialists from the headquarters of the American occupation forces. It was then presented to Parliament by the government and adopted by it in October 1946, and came into force on May 3, 1947. The Constitution adopted many principles of Anglo-Saxon law, innovations in constitutional law of the time (for example, provisions on socio-economic rights) and demonstrated a democratic approach to the regulation of social relations.

The Constitution consists of a preamble, 11 chapters and 103 articles that regulate the status of the emperor, renunciation of war, the rights and duties of the people, the legal status of Parliament, the Cabinet, the judiciary, public finances, local government, and the procedure for changing constitutional norms.

For the first time in Japanese history, it proclaims the principles of popular sovereignty, the supremacy of Parliament, and the election of both houses (the non-elected nature of the upper house was abolished, as was the case before 1945).

Japan is a constitutional, parliamentary monarchy, where the power of the emperor is reduced to a minimum; he remains only a symbol of the nation. The Parliament was proclaimed the highest and only legislative body.

The government is formed with the decisive role of Parliament and is responsible to it. Japan is proclaimed a unitary state with broad local autonomy of administrative and territorial units.

The Constitution established the status of man and citizen on a new basis. The Japanese have a wide range of basic rights and freedoms. Constitutional norms abolished privileged classes, proclaiming the principle of equality (equality of all before the law, as well as the inadmissibility of any discrimination). Characteristic here is the provision in the basic norms that any awards are valid only during the life of the given person. Equality of the sexes is proclaimed. The issues of marriage are regulated in detail, which should be concluded only on the basis of mutual consent of the parties.

The body of constitutional control is the Supreme Court, which, as in the United States, has the right to make a final decision on the unconstitutionality of a normative act. However, in Japan, a special case is filed in the trial court alleging the unconstitutionality of an act, and the case can be brought up to the Supreme Court in a hierarchical manner.

77about the method of change The Japanese Constitution is rigid. Its change is possible only on the initiative of Parliament. To amend it, the consent of two-thirds of the total number of members of each of the two chambers is required. Ratification of the amendment is carried out either by a referendum or by a new Parliament formed after national elections. The method of ratification is determined by Parliament. The approved amendments are immediately promulgated by the Emperor as an integral part of the Constitution. Until now, not a single amendment has been made to the Constitution.

Constitutional status of the Emperor of Japan.

Emperor - the throne is passed on by succession to a member of the Family empire. Preference is given to the eldest son of the emperor. A female person cannot be inherited.

The reign of each emperor was proclaimed. Defined by Era, acc. chronicles are being written about the cat. From Jan. 1989, after the death of Emperor Hirohito, his son Anihito was proclaimed emperor - the Era of Peace (125 in a row).

According to the Constitution, the emperor is a symbol of the state and the unity of the people. He is not vested with powers related to the implementation of government. authorities. All his actions could be... adopted with the approval and advice of the Cabinet of Ministers, which is responsible.

The Emperor carries out the following types of activities: promulgation by constitutional law; confirmation of amnesty; mitigation of punishment; restoration of rights; awarding awards; reception of foreign ambassadors; implementation of the ceremony.

In accordance with the law on imperial duty, the succession to the throne is protected by the council of the imperial court.

The Cabinet carries out its functions on the basis of customs. Discussion of issues and preparation of decisions takes place in secrecy. Decisions are made by unanimity, not by vote.

Parliament of Japan.

Japan's form of government is a parliamentary monarchy. Parliament is the highest body of state power and the unified legislative body of the state, consists of 2 chambers: 1) the chamber of chairmen; 2) House of Councillors.

The lower house can be dissolved early at the request of the government. Each chamber can independently elect its chairman and officers, establish its own rules for meetings and procedures for internal discipline.

The Law on Parliament includes the following as officials: chairmen, vice-chairman, temporary chairmen, chairmen of committees and the secretary general of the chambers.

The traitor's deputy receives his post from among the deputies of the apposition party. The meeting of the chambers is open and minutes are taken. The minutes must be published and distributed to the public. The decision is made by a majority vote. 3 forms of voting are used: 1) voting - standing. 2) secret voting, in which voters put ballots into ballot boxes: white - for, blue - against. During a roll call vote, the deputy covers the nameplate. 3) voting - no objection. If there are none, a decision is made; if so, they resort to other forms of voting.

Deputies have immunity for the duration of the session. Home. Parliamentary faction – adoption of laws and state. budget. Laws are adopted by a decision of both chambers. If the House of Councilors rejects the Bill, it becomes law after its second vote. Adoption by a majority of at least 2/3 of the votes of the lower chamber deputies present.

All adopted bills are signed by the minister responsible for their responsibility. and are countersigned by the Prime Minister after dispatch for promulgation on behalf of the people.

Parliament approves international treaties concluded by the Government. Ch. a form of parliamentary control over the activities of the government is interpellation (interrogation of a parliamentarian).

Government of Japan.

In accordance with the Constitution, the Cabinet of Ministers exercises executive power. It consists of the Prime Minister, 12 ministers responsible for a specific area of government, and 8 “ministers without portfolio” who are advisers to the Prime Minister.

Japan is characterized by enlarged ministries with significant powers and functions, but with a small staff of employees. The status of the Cabinet of Ministers is regulated by the Constitution, the Law on the Cabinet of Ministers of 1947, and the Law on the Structure of State Executive Bodies of 1948. According to these legislative acts, the government is formed in a parliamentary manner, and the majority of government ministers must be elected from members of Parliament. The first issue put up for discussion by the newly elected Parliament is the nomination of the Prime Minister. As a rule, the head of government becomes the leader of the party or bloc that wins the elections.

The Prime Minister is nominated by a resolution of Parliament from among its members. This nomination must precede all other business of Parliament. If the House of Representatives and the House of Councilors have adopted different resolutions on the nomination and if agreement has not been reached through a joint meeting of both houses provided for by law, or if the House of Councilors has not decided on the nomination within ten days, excluding the time of recess of Parliament, thereafter Once the House of Representatives has made such a nomination, the decision of the House of Representatives becomes a decision of Parliament.

If the office of Prime Minister becomes vacant or if the first session of Parliament is convened after the general election of members of the House of Representatives, the Cabinet must resign as a whole.

After election, all members of the government are approved by a special decree of the emperor. The Head of the Cabinet has the right to remove individual ministers from office at his discretion. The Cabinet is collectively responsible to Parliament. Ministers of state while occupying their positions cannot be brought to justice without the consent of the Prime Minister. However, this does not affect the right to prosecute.

The Prime Minister, as a representative of the Cabinet, introduces bills to Parliament, reports to Parliament on the general state of government affairs and foreign relations, and also exercises control and supervision over various branches of government.

The Prime Minister and other ministers of state, whether members or non-members of either House, may attend meetings of either House at any time to speak on bills. They should also attend meetings if necessary to provide answers and clarifications.

Judicial branch in Japan.

The judicial branch is headed by the Supreme Court. It consists of a chief judge appointed by the emperor on the recommendation of the cabinet and 14 judges appointed by the cabinet (15 in total). To the top. The court has 3 divisions of 5 judges. The quorum for the plenary court is 9 members, for the division – 3 members. Top. The court exercises constitutional control and is also the final authority for consideration of other cases; studies instructions for lower courts; summarizes judicial practice. Kon-Ya establishes referential responsibility for members of the top. Courts, that is, every 10 years, simultaneously with elections to the lower house of parliament, voters vote for or against specific judges. With a majority vote, the judge resigns (but this did not happen in Japan). Higher courts have several divisions and are the court of 1st instance in cases of state affairs. Crimes as well as the appellate court for criminal and civil cases. I'm doing. Almost 50 district courts located in each prefecture are divided into several branches and consider the bulk of criminal and civil cases. They are the appellate authority for disciplinary courts. The lowest level is the disciplinary courts. Cases in them are considered by a single judge and it is not necessary for the judge to have a legal education. Family courts have a special system. They operate at district courts and consider disputes about inheritance, minor criminal cases, disputes related to family law, etc.

⇐ Previous10

Recommended pages:

Use the site search:

CHAPTER VI. JUSTICE

Article 76. Full judicial power belongs to the Supreme Court and the lower courts established by law.

No special courts may be established. Administrative bodies cannot administer justice with the right to make a final decision.

All judges are independent and carry out their functions guided by their conscience; they are bound only by this Constitution and laws.

Article 77. The Supreme Court is empowered to establish rules of legal proceedings, the legal profession, internal regulations in the courts, as well as rules for managing the affairs of the judiciary.

Prosecutors must follow rules set by the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court may delegate to lower courts the power to set rules for its operation.

Article 78 Judges may not be removed from office without trial by public impeachment, except in cases where the judge is declared mentally or physically incapable of performing his duties by a court of law. Administrative authorities cannot apply disciplinary sanctions to judges.

Article 79. The Supreme Court consists of a Chairman and other judges, the number of which is established by law; all judges, with the exception of the Chairman, are appointed by the Cabinet.