Probably, almost everyone imagines what ancient Japanese drawings depicting sexual scenes look like, sometimes even too openly, but not everyone knows that this type of art is called shunga.

The name of this type of painting is translated as “image of spring.” By spring, the Japanese often mean sex. In general, shunga contain a lot of symbolism in their pictures, for example, the buds of plum flowers symbolize innocence, and the unfolded fabric symbolizes the approach of ejaculation.

Erotica as art

At the British Museum's exhibition of erotic woodcuts, Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art, you quickly realize how wrong it would be to dismiss the works on display as mere pornography.

Exhibition curator Tim Clark says: "I think people are surprised by these sexually explicit works, their beauty and humor and, of course, great humanism."

Tim Clark, exhibition curator

One of his favorite works of the 165 included in the catalog is a set of 12 prints by Torii Kiyonaga (1752-1815). The hugging figures are drawn exceptionally subtly, and the bold framing of the compositions allows the viewer to feel even more clearly the reality of the scenes depicted.

Clark says he admires most of all the “sensibility and sophistication of the carvers and printers” who turned the fine lines of Kiyonaga’s drawings into woodcuts.

The exhibition of shunga paintings is the result of a research project that started in 2009 and involved 30 collaborators. The goal of the project is to “recover a collection of works and subject them to critical analysis,” says Clarke.

About 40% of the works presented at the exhibition belong to the British Museum, where shunga began to be collected in 1865. A significant part of the remaining work belongs to the International Research Center for Japanese Studies in Kyoto.

Clark's favorite definition of shunga is “sexually explicit art,” with the emphasis on the word “art.” It. Surprisingly, almost all famous Japanese artists of that time painted shunga.

As the exhibit explains, early shungas were made from expensive materials. They were valued and passed down from generation to generation. It is recorded that one picturesque scroll of shunga cost fifty momme of silver - an amount sufficient at that time to buy 300 liters of soybeans.

In addition to the completely obvious, shunga also has unusual uses. They were believed to have the ability to strengthen the courage of warriors before battle, and were also a talisman that protected against fire.

In addition to its entertainment value, shunga also served an educational function for young couples. And despite the fact that their authors were exclusively men, it is believed that many women also liked to look at these drawings.

Nishikawa Sukenobu Shunga. A man seduces a young woman; a shamisen lies on the floor behind him. Hand-colored woodcut with green background. The same print, but uncolored, is in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. (1711-1716)

Painting, horizontal scroll, shunga. One of 12 erotic encounters. An adult samurai and a young girl are hugging under a blanket. A woman straightens her bed. Ink, paint, gold and silver pigment, gold and silver leaf on paper. Without a signature. (Early 17th century)

Many prints show sexual pleasure as mutual caresses. “They are strongly connected to everyday life,” says Clark. “Sex is often depicted in everyday settings, between husbands and wives.”

The print shown at the very beginning of the exhibition is such an example. The Pillow Poem by Kitagawa Utamaro (d. 1806) depicts lovers in a room on the second floor of a tea house. Their bodies are intertwined under luxurious clothes, and he looks passionately into her eyes. Her buttocks are visible from under the kimono.

“The Pillow Poem” (Utamakura), Kitagawa Utamaro. Shunga, colored woodcut. No. 10 of 12 illustrations of a printed folding album (set of individual sheets). Lovers in a closed room on the second floor of a tea house. Inscribed and signed. (1788)

Often, it was fashionable kimonos, decorated with hand-painted and embroidered designs, intricate hairstyles, and eye-catching accessories that were more important in these engravings than the images of the beauties themselves. As a rule, the objects of the image were courtesans from the so-called gay quarters that were in any large city. An example of this is the Yoshiwara quarter, which was located in the northern part of Edo, on the opposite bank of the Sumidagawa River from the center.

Three times a year - in the spring during the cherry blossoms, in the summer during the peony blossoms and in the autumn during the chrysanthemums - a parade of the most attractive and popular beauties was held in Yoshiwara, on the central street of Nakanotyo. After the parade of all the “flowers,” as the courtesans were figuratively called, portraits of oiran were released - high-ranking courtesans with their students and maids (kamuro and shinjo), walking along the street in all their splendor.

The emergence of the genre of bijin-ga (images of beautiful women), as well as the appearance of easel engravings on separate sheets (ichimai-e) is associated with the name of Hishikawa Moronobu.

In the first half of the 18th century. One of the largest schools of ukiyo-e painting was the Kaigetsudo dynasty. The masters of this school created picturesque full-length portraits of courtesans in bright colorful costumes against neutral backgrounds. These were images that served as a kind of advertisement for famous beauties, popular inhabitants of cheerful neighborhoods. The interest in the inhabitants of the cheerful neighborhoods was so great among the townspeople that soon images of beauties appeared in interiors, captured at different times of the day. The ideal of female beauty changed over time; in the second half of the 18th century, the tall beauties of the artists of the Kaigetsudo school were replaced by the petite young girls of Suzuki Harunobu and Isoda Koryusai, and at the turn of the 18th–19th centuries, beauties of a more mature age came into fashion again, depicted in the engravings of Kitagawa Utamaro. and Torii Kiyonaga. In addition to full-length ceremonial portraits and images in a chamber, intimate setting, full-length portraits of okubi-e, or “big heads,” are becoming fashionable, marking the growing interest of artists in conveying the emotional states of their heroines.

One of the most famous ukiyo-e artists, who largely determined the characteristics of Japanese classical woodcuts during its heyday, was Kitagawa Utamaro (1753–1806). Many of his beautiful albums and series of easel engravings appeared as a result of a long collaboration with the famous publisher Tsutaya Juzaburo. Utamaro became famous primarily for his bust-length portraits of courtesans, as well as polyptychs with genre scenes, illustrated albums, and series with paired portraits of lovers. Now these are not only courtesans or maids from tea establishments, but also simply city women going about their daily activities.

Artists of this period paid more attention to the relationship between the characters - mother and child, the legendary couples in love.

In the engravings of artists of the Kikugawa dynasty (Eizan, Eisen), who worked in the first half of the 19th century, you can see beauties in magnificent costumes. The draperies of the kimono completely hide the figure, the ornament is interpreted brightly and flatly, the line becomes broken and fractional.

The Birth of Frankness

It all started around the 14th century. Shunga artists were inspired by nothing other than Chinese medical collections, which depicted naked people in all honesty. But shunga reached its peak already in the 17th century, during the Edo period.

The authorities often did not like such looseness of citizens, and attempts were made to ban explicit images more than once. During the reforms of 1772, not only shunga was banned, but in general all new books had to undergo strict censorship.

Europeans did not understand such art. Francis Hall, an American publisher who moved to Japan in the 19th century, was shocked when he was shown examples of shunga. And even in 1975, Peter Webb, a shunga researcher, noted that such images “cannot be displayed in public.”

Shunga: A Brief History of Japanese Pornographic Painting

"Shunga" is Japanese erotic art. That is, now it is simply called “erotic”, that is, a rather soft, even delicate word - just a few years ago it was difficult to imagine that shunga would not only reach Western culture, but also gain a certain popularity. Literally, the word “shunga” means “image of spring.” "Spring" in Japanese is a common euphemism for sex. The Birth of Frankness It all began around the 14th century. Shunga artists were inspired by nothing other than Chinese medical collections, which depicted naked people in all honesty. But shunga reached its peak already in the 17th century, during the Edo period.

The authorities often did not like such looseness of citizens, and attempts were made to ban explicit images more than once. During the reforms of 1772, not only shunga was banned, but in general all new books had to undergo strict censorship. Shunga went underground, but did not disappear. Europeans did not understand such art. Francis Hall, an American publisher who moved to Japan in the 19th century, was shocked when he was shown examples of shunga. And even in 1975, Peter Webb, a shunga researcher, noted that such images “cannot be displayed in public.” Fans and admirers It's funny, but among the shunga fans there were both men and women of all classes. There were many superstitions around the explicit paintings. For example, samurai took shunga with them, believing that it would protect them from death.

Merchants kept shunga in their warehouses, believing that images of men and women having sex would protect the warehouse from fire. However, what worked against this assumption was that almost all shunga-keeping groups had very limited access to the opposite sex: samurai lived for months in each other's company, and merchants traveled widely to purchase goods from other countries. Thus, perhaps the storage of shunga was purely sensual and not superstitious. Shunga also served as a kind of “instruction” for the sons and daughters of wealthy families who were about to get married. However, this version also has opponents - often the lovers depicted in shunga had sex in such positions that the presence of bones in them raised serious doubts.

In addition, in Japan there were also ordinary “manuals”, where more precise instructions were given both regarding sexual intercourse and regarding intimate hygiene. Shunga Characters Although most shunga depicted sexual relationships between ordinary people (townspeople, farmers and merchants), occasionally the Dutch or Portuguese appeared in the paintings. A separate direction of shunga can be considered the depiction of courtesans. For example, the artist Utamaro is known for painting the beautiful courtesans of Tokugawa. In those days, among the population, courtesans were considered almost celebrities - like Hollywood stars. They radiated a flair of eroticism and inaccessibility - after all, only very rich people could afford to pay for their services.

That is why for many men, courtesans have become a kind of fetish. Much later, works depicting courtesans were subjected to severe criticism. Artists were accused of idealizing the life of prostitutes in the “pleasure quarters.” However, Utamaro tried to depict not only the sensual life, but also the inner world of the courtesan: many of his characters, for example, dream of getting married and escaping from their work. Another frequent shunga character was kabuki actors, who often worked as gigolos, and an additional element of eroticism was their youth. They were often depicted in the company of courageous samurai.

Miyagawa Isso, a 17th-century Japanese artist, often depicted kabuki actors and sumo wrestlers. Shunga Symbolism However, many shunga can hardly be considered naturalistic depictions of sex. This becomes obvious when looking at the huge genitals and the shocking and humorous situations depicted in many of the prints. There are many similarities between erotic shunga and what is known as warai-e, or “funny pictures.”

Humor in shunga can be both sharp and obscene. As with much of the folk culture of the Edo period, and certainly with the sexually explicit art of more modern eras, there is an element of rebellion. Shunga was often accompanied by written explanatory texts and dialogues. But there are also other, not so straightforward symbols in the images. For example, plum blossom buds mean virginity, and unfolded tissue means impending ejaculation. It is curious, by the way, that people in most shunga are depicted dressed. This happens because the Japanese do not consider nudity particularly attractive: they often see each other naked in public baths. Additionally, clothing helps readers differentiate between courtesans and foreigners. Prints on clothing also often carry symbolism and also draw attention to exposed parts of the body - usually the genitals.

(WITH.)

Story

Shunga appeared in China. It is believed that the ancestors of the genre were illustrations in Chinese medical manuals that appeared in Japan during the Muromachi period (1336-1573). In addition, Zhou Fang was an influential painter during the Chinese Tang Dynasty. He, like many erotic artists of his time, exaggerated the size of the genitals in his works. This became a characteristic feature of shunga.

In Japan, the history of shunga dates back to the Heian period. They depicted sexual scandals at the imperial court and in monasteries, and the characters were usually courtiers and monks. The style became widespread during the Edo period (1603–1867). Thanks to the woodblock printing technique, the quantity and quality of shunga has increased dramatically. There were repeated government attempts to ban shunga, most notably in 1661, the Tokugawa shogunate issued a decree banning, among other things, erotic books known as koshokubon

(Japanese: 好色本

ko: shokubon

). Although other genres of art mentioned in the decree, such as works criticizing daimyos and samurai, became illegal, shunga continued to be created without much difficulty. The 1772 decree was more strict: it was forbidden to publish any new books that had not received official permission from the city ruler. Shunga also became illegal. There is, however, a possibility that even in this form the genre continued to flourish, as it was in demand.

The spread of Western culture and technology at the beginning of the Meiji period (1868–1912), in particular the import of photographic reproduction techniques, had serious consequences for shunga. Woodcuts were preserved for a time, but the characters began to be depicted in European clothes and hairstyles. Eventually, shunga could no longer compete with erotic photography, which led to its demise.

Shunga of the Meiji period. A man with a European hairstyle copulates with a woman in a traditional Japanese costume

Login to the site

Traditional Japanese aesthetics in the modern world Shunga painting: how Japanese erotic art made a splash in London The largest exhibition on the theme of “sex and pleasure in Japanese art” Tony McNichol

[17.01.2014] |

Japanese traditional ukiyo-e painting has always amazed foreigners with its grace and liveliness. However, not all of them know that in addition to the famous scenes of village and city life, many well-known artists of that time were also the authors of a large number of sexually explicit paintings. The works, known as shunga, are marked by tenderness, a sense of humor and biting satire. The exhibition Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art, held at the British Museum, enjoyed unprecedented popularity among the London public. Writer Tony McNichol decided to take a closer look at this most intimate of art genres.

Erotica as art

His beak caught firmly In the shell of a mollusk, The snipe cannot fly away On the autumn evening. (Yadoya no Mashimori)

At the British Museum's exhibition of erotic woodcuts, Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art, you quickly realize how wrong it would be to dismiss the works on display as mere pornography.

Exhibition curator Tim Clark says: “I think people are surprised by these sexually explicit works, their beauty and humor and, of course, great humanism.”

Tim Clark, exhibition curator

One of his favorite works of the 165 included in the catalog is a set of 12 prints by Torii Kiyonaga (1752-1815). The hugging figures are drawn exceptionally subtly, and the bold framing of the compositions allows the viewer to feel even more clearly the reality of the scenes depicted.

Clark says he admires most of all the “sensibility and sophistication of the carvers and printers” who turned the fine lines of Kiyonaga's drawings into woodcuts.

The exhibition of shunga paintings is the result of a research project that started in 2009 and involved 30 collaborators. The goal of the project is to “recover a collection of works and subject them to critical analysis,” says Clarke.

About 40% of the works presented at the exhibition belong to the British Museum, where they began collecting shunga in 1865. A significant part of the remaining work belongs to the International Research Center for Japanese Studies in Kyoto.

Clark's favorite definition of shunga is “sexually explicit art,” with the emphasis on the word “art.” He notes that “we in the West have not had such a combination of sexually explicit and artistically beautiful until recently.” Surprisingly, almost all famous Japanese artists of that time painted shunga.

As the exhibit explains, early shungas were made from expensive materials. They were valued and passed down from generation to generation. It is recorded that one pictorial scroll of shungisti cost fifty momme of silver - an amount sufficient in those days to buy 300 liters of soybeans.

In addition to the completely obvious, shunga also has unusual uses. They were believed to have the ability to strengthen the courage of warriors before battle, and were also a talisman that protected against fire.

In addition to its entertainment value, shunga also served an educational function for young couples. And despite the fact that their authors were exclusively men, it is believed that many women also liked to look at these drawings.

Nishikawa Sukenobu Shunga. A man seduces a young woman; a shamisen lies on the floor behind him. Hand-colored woodcut with green background. The same print, but uncolored, is in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. (1711-1716)

Painting, horizontal scroll, shunga. One of 12 erotic encounters. An adult samurai and a young girl are hugging under a blanket. A woman straightens her bed. Ink, paint, gold and silver pigment, gold and silver leaf on paper. Not signed. (Early 17th century)

Many prints show sexual pleasure as mutual caresses. “They are strongly connected to everyday life,” says Clark. “Sex is often depicted in everyday settings, between husbands and wives.”

The print shown at the very beginning of the exhibition is such an example. “The Pillow Poem” by Kitagawa Utamaro (d. 1806) depicts lovers in a room on the second floor of a tea house. Their bodies are intertwined under luxurious clothes, and he looks passionately into her eyes. Her buttocks are visible from under the kimono.

“The Pillow Poem” (Utamakura), Kitagawa Utamaro. Shunga, colored woodcut. No. 10 of 12 illustrations of a printed folding album (set of individual sheets). Lovers in a closed room on the second floor of a tea house. Inscribed and signed. (1788)

A world of humor and satirical allusions

Kawanabe Kiyosai

However, much of shunga can hardly be considered naturalistic depictions of sex. This becomes obvious when looking at the huge genitals and the shocking and humorous situations depicted in many of the prints. There are many similarities between erotic shunga and what is known as warai-e, or “funny pictures.”

The left scroll of a pictorial triptych by Kawanabe Kiyosai (1831-1889) from the early Meiji era depicts a passionately embracing couple. The back shows a playful kitten with bare claws, whose attention is clearly drawn to the most sensitive parts of the male anatomy. The viewer can guess what happened next.

“In fact, I often wanted to laugh when looking at these pictures,” comments exhibition visitor Jess Oboiro. “For some reason, the Sunday crowd was in a kind of quiet reverie... although, naturally, that’s not the mood in which to view this type of art, is it?”

Humor in shunga can be both sharp and obscene. As with much of the folk culture of the Edo period, and certainly with the sexually explicit art of more modern eras, there is an element of rebellion.

“Shunga constantly turns to more serious genres of art and literature, parodying them, often as a joke, but sometimes with sharp political overtones,” says Clark.

One example is shunga versions of moral education books for women. Sometimes sexually explicit parodies are so similar that they appear to be made by the same artists and publishers as the originals. In fact, they actually come from the same publishing background.

However, when shunga satire got too close to the truth, censorship immediately appeared. Declared illegal in 1722, shunga was banned for two decades. Later, similar persecutions also occurred, but the art of shungin never completely disappeared. It skillfully used its semi-legal status to reach new levels of satire. Many shunga still amaze with their boldness and freedom of imagination.

One set in the exhibition features portraits of kabuki actors and enlarged images of their erect penises. The style of the pubic hair follows the actors' wigs, and the bulging veins match the lines of their makeup.

Shunga in modern Japan

“The simple-minded type” (Uwaki no so) from “Ten physiognomic types of women” (Fujin sogaku jittai), Kitagawa Utamaro. Colored woodcut with background covered with mica powder. The head of the girl wiping her hands on the cloth is turned, her chest is visible. Inscribed, signed, sealed and marked. (1792-1793)

Ironically, soon after shunga gained fame in the West (Admiral Perry was given shunga as a “diplomatic gift”, and Picasso, Rodin and Lautrec were real fans of the genre), the Japanese decided that it was time to end this art. It was only in the 70s of the 20th century that a shunga exhibition, which had been persecuted for years, was held in Japan.

This exhibition reaffirms the importance of shunga to all Japanese art. However, even now, according to researchers, it would be difficult to imagine an exhibition on the same scale in Japan as in the British Museum.

“It is clear that shunga was an integral part of Japanese culture until at least the 20th century,” says Andrew Gerstle, professor of Japanese studies at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London. “People are surprised that it is still impossible to hold such an exhibition in Japan itself.”

According to Clarke, the response to their exhibition in both the UK and Japan has been “absolutely phenomenal”. Only half the time allotted for the exhibition has passed, and they are already approaching the planned number of visitors.

Exhibition co-author Yano Akiko, a research fellow at the Center for Japanese Studies at SOAS, said the team had gone to great lengths to explain to visitors “a complex phenomenon that predates our era.”

“I was a little worried that we were trying to give too much information,” she says. “However, the majority of visitors seemed to really enjoy the exhibition - they fully accepted the content of the exhibition and understood what we wanted to convey. It was the best reaction we could imagine.”

(Original article written in English. Images from the collection of the British Museum).

Another interesting read is Shunga - a frivolous Japanese print

History of hand-drawn erotic stories

The first drawings date back to the fourteenth century, and pictures appeared in China in medical reference books, and by the seventeenth century shunga had already reached its peak in Japan. Then Japanese culture reached its golden age, and the inhabitants attached quite a lot of importance to sensual pleasures.

Most often, the pictures depicted the sex life of ordinary townspeople, although you can also see samurai and sumo wrestlers and even foreigners: the Dutch or the Portuguese. You can also meet a lot of Tokugawa courtesans; they were also captivating and inaccessible, like now catwalk stars or film actresses - only the rich and famous Japanese could use their services.

It is not difficult to guess that the excessive romanticization of the lives of women with not the most correct behavior caused a lot of criticism, although the world of courtesans was not always shown as ideal. Kabuki actors were also portrayed alongside the courtesans, who also did not always lead a righteous life, earning extra money by providing sexual services, which, judging by the images, even samurai used.

The pictures did not always depict traditional or even gay sex. Sometimes there are completely unusual stories. In one of the most famous drawings, for example, a woman clearly enjoys the caresses of two octopuses. Although, judging by the description, the woman did not do this entirely of her own free will, completely different emotions are clearly visible on her face.

A world of humor and satirical allusions

Kawanabe Kyosai

However, much of shunga can hardly be considered naturalistic depictions of sex. This becomes obvious when looking at the huge genitals and the shocking and humorous situations depicted in many of the prints. There are many similarities between erotic shunga and what is known as warai-e, or “funny pictures.”

The left scroll of a pictorial triptych by Kawanabe Kyosai (1831-1889) from the early Meiji era depicts a passionately embracing couple. The back shows a playful kitten with bare claws, whose attention is clearly drawn to the most sensitive parts of the male anatomy. The viewer can guess what happened next.

Humor in shunga can be both sharp and obscene. As with much of the folk culture of the Edo period, and certainly with the sexually explicit art of more modern eras, there is an element of rebellion.

One example is shunga versions of moral education books for women. Sometimes sexually explicit parodies are so similar that they appear to be made by the same artists and publishers as the originals. In fact, they actually come from the same publishing background.

However, when shunga satire got too close to the truth, censorship immediately appeared. Declared illegal in 1722, shunga was banned for two decades. Later, similar persecutions also occurred, but the art of shunga never completely disappeared. It skillfully used its semi-legal status to reach new levels of satire. Many shunga still amaze with their boldness and freedom of imagination.

One set in the exhibition features portraits of kabuki actors and enlarged images of their erect penises. The style of the pubic hair follows the actors' wigs, and the bulging veins match the lines of their makeup.

Pre-Columbian America

The most outspoken and sexual civilization of pre-Columbian South America was not the Aztecs or Incas, but the Moche culture, who lived in northern Peru from 100 to 800 AD.

Their representatives were skilled craftsmen. They were especially good at ceramics. About 500 ceramic items with sexual scenes were found.

Most often, the Moche depicted anal sex, while vaginal sex was depicted on their products extremely rarely.

There was also blowjob, but cunnilingus - never.

Most of the couples are men and women, and the genitals of the partners are depicted in great detail.

Images of skeletons being masturbated by living women were also found.

Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt is the birthplace of sundials, calendars, paper, ink and pornography. In fact, the ancient Egyptians, apparently, knew a lot about perversion.

Turin erotic papyrus, reconstruction

It was in Egypt that the first “prehistoric Playboy” was found - the Turin erotic papyrus, consisting mainly of various images of sex scenes. It dates back to 1292−1075 BC.

Men giving themselves blowjobs, papyrus, 1070 - 664 BC.

Despite the fact that most people in Egypt were not involved in incestuous relationships, the Egyptian gods did not shy away from them, and, imitating them, the rulers also leaned towards them - the pharaohs willingly married their own sisters.

Limestone sculpture, erotic group, 332 - 283 BC.

But as for virginity before marriage, the Egyptians, apparently, did not give a damn about it - it was mainly the Romans who professed such morality.

Erotic scene between a man and a woman, 332 BC. - 337 AD

Ancient Greece and Rome

The ancient Greeks were very consistent in their sexual preferences. It was the culture of Ancient Greece that showed us what homosexual relationships between men look like.

It is noteworthy that the wife, according to the ancient Greeks, served exclusively for childbearing, while for pleasure they preferred young men (or prostitutes).

Older men had to raise young men - instruct and take care of them, including teaching them the art of pleasure. At the same time, intimate relationships between two adult men were considered obscene.

The ancient Greeks often depicted sex scenes on ceramic amphorae. Strictly speaking, they depicted scenes of everyday life: some of them were more erotic, some less.

Many drawings with sexual scenes were found in excavations of Roman buildings in Pompeii and Herculaneum.

Two men and one woman making love, fresco, Pompeii, 79 BC.

Leda and the Swan, Pompeii, 50−79 AD.

Wine cup with pentathlon participants, 505 - 500 BC. uh

Amphora with erotic subjects, c. 510 BC

India

There is not an adult who has not heard anything about the Kama Sutra - an ancient Indian treatise dedicated to sensual bodily love.

Sexuality in the minds of the ancient Hindus was an obligatory part of spiritual growth, inseparable from the mental sphere.

Of course, this was reflected in their visual culture. The most famous explicit statues reflecting human passion are the bas-reliefs from the “temple of love” of Khajuraho. Stone lovers do things we never dreamed of.

In addition, their famous miniatures are considered classics of Indian erotic art.

Hundreds of ukiyo-e prints from Japanese masters of the 19th century have been made publicly available

This direction of Japanese fine art is familiar to everyone, but not everyone knows that it is called ukiyo-e (images of the changing world).

The word ukiyo, literally translated as "floating world", is a homophone to the Buddhist term "world of sorrow", but is written in different characters. The term "ukiyo" was originally used in Buddhism to mean "the mortal world, the vale of sorrow", but in the Edo era, with the advent of specially designated city blocks in which the Kabuki theater flourished and the houses of geishas and courtesans were located, the term was rethought, and often became understood as “the world of fleeting pleasures, the world of love,” says Wikipedia.

Ukiyo-e prints are a type of woodcut. They were painstakingly created and flourished from the 17th to the 19th centuries, and their main subjects were picturesque landscapes, beautiful geishas, sumo wrestlers and kabuki actors.

The prints were in particular demand among middle-class Japanese, who decorated their walls with them. And after the Meiji Revolution, when the country opened its borders to foreigners, European art critics began to buy ukiyo-e en masse.

Currently, the online collection of the Vincent Van Gogh Museum contains over five hundred digitized images from the famous masters of ukiyo-e prints. You can search by artist name, year, or print type, download them in high resolution, and enjoy elegiac and timeless works of Japanese fine art.

Cowsheds on Takanawa, from the series “Views of famous places along the Tokaido”, Kawanabe Kyosai, 1863

Nihonbashi, from the series “Famous Places Along the Tokaido”, Utagawa Kunisada, 1863

Right side of triptych depicting the Oigawa River, from the series “53 Stations of the Tokaido”, Utagawa Kunimasa, 1849-1853

Peonies at Hachiman Shrine, Fukagawa, Utagawa Hiroshige II, 1864

Depiction of visitors using the services of the Gankiro tea house in Yokohama, Yoshikazu Utagawa, 1860

Pleasant Time at Mitsuiji Hot Springs, right side of triptych, Utagawa Kunisada, 1861

Evening view of flowers, Utagawa Kunisada, 1861

Boat Journey, Edo, Utagawa Kunisada, 1860

Divers from Ise, right side of triptych, Utagawa Kunisada, 1860

Green moon, admiring cherry blossoms, right leaf of triptych, Toyohara Kunichika, 1868

New Year's Celebration, 1875-1900

Lotus, finch and cicadas. Gyozan, 1875-1900

Cranes and sakura. Togaku, 1875-1900

Admiring a plum blossom, Tokyo, 1875-1900

Yokkaichi: Mi River and Nako Bay. From the series “53 Stations of Tokaido”, Utagawa Hiroshige, 1855

Bridge in a province with deep traditions, central part of a triptych, Utagawa Fusatane, 1860

On the River Bank, Utagawa Kunisada, 1820-1830

Parody of a drinking party in Oeyama, the central part of a triptych, Toyohara Kunichika, 1864

See also:

- Vintage Japanese erotica in a new way

- The Morgan Library has opened up access to hundreds of Rembrandt prints

- The National Museum of Sweden has made 3,000 paintings available for free access

- The National Galleries of Scotland have posted a rich collection of masterpieces online

April 18, 2017

Shunga in modern Japan

“The simple-minded type” (Uwaki no so) from “Ten physiognomic types of women” (Fujin sogaku jittai), Kitagawa Utamaro. Colored woodcut with background covered with mica powder. The head of the girl wiping her hands on the cloth is turned, her chest is visible. Inscribed, signed, sealed and marked. (1792-1793)

Ironically, soon after shunga became famous in the West (Admiral Perry was given shunga as a “diplomatic gift”, and Picasso, Rodin and Lautrec were real fans of the genre), the Japanese decided that it was time to end this art. It was only in the 70s of the 20th century that an exhibition of shunga, which had been persecuted for years, was held in Japan.

This exhibition reaffirms the importance of shunga to all Japanese art. However, even now, according to researchers, it would be difficult to imagine an exhibition on the same scale in Japan as in the British Museum.

“It is clear that shunga was an integral part of Japanese culture until at least the 20th century,” says Andrew Gerstle, professor of Japanese studies at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London. “People are surprised that it is still impossible to hold such an exhibition in Japan itself.”

According to Clarke, the response to their exhibition in both the UK and Japan has been "absolutely phenomenal". Only half the time allotted for the exhibition has passed, and they are already approaching the planned number of visitors.

Exhibition co-author Yano Akiko, a research fellow at the Center for Japanese Studies at SOAS, said the team had gone to great lengths to explain to visitors "a complex phenomenon that predates our era."

“I was a little worried that we were trying to give too much information,” she says. “However, the majority of visitors seemed to really enjoy the exhibition - they fully accepted the content of the exhibition and understood what we wanted to convey. It was the best reaction we imagined."

Shunga painting: how Japanese erotic art made a splash in London

Erotica as art

His beak caught firmly In the shell of a mollusk, The snipe cannot fly away On the autumn evening.

(Yadoya no Mashimori) At the British Museum's exhibition of erotic woodcuts, Shunga: Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art, you quickly realize how wrong it would be to dismiss the works on display as mere pornography.

Exhibition curator Tim Clark says: “I think people are surprised by these sexually explicit works, their beauty and humor and, of course, great humanism.”

Tim Clark, exhibition curator

One of his favorite works of the 165 included in the catalog is a set of 12 prints by Torii Kiyonaga (1752-1815).

The hugging figures are drawn exceptionally subtly, and the bold framing of the compositions allows the viewer to feel even more clearly the reality of the scenes depicted.

Clark says he admires most of all the “sensibility and sophistication of the carvers and printers” who turned the fine lines of Kiyonaga's drawings into woodcuts.

The exhibition of shunga paintings is the result of a research project that started in 2009 and involved 30 collaborators. The goal of the project is to “recover a collection of works and subject them to critical analysis,” says Clarke.

About 40% of the works presented at the exhibition belong to the British Museum, where shunga began to be collected in 1865. A significant part of the remaining work belongs to the International Research Center for Japanese Studies in Kyoto.

Clark's favorite definition of shunga is “sexually explicit art,” with the emphasis on the word “art.” He notes that “we in the West have not had such a combination of sexually explicit and artistically beautiful until recently.” Surprisingly, almost all famous Japanese artists of that time painted shunga.

As the exhibit explains, early shungas were made from expensive materials. They were valued and passed down from generation to generation. It is recorded that one picturesque scroll of shunga cost fifty momme of silver - an amount sufficient at that time to buy 300 liters of soybeans.

In addition to the completely obvious, shunga also has unusual uses. They were believed to have the ability to strengthen the courage of warriors before battle, and were also a talisman that protected against fire.

In addition to its entertainment value, shunga also served an educational function for young couples. And despite the fact that their authors were exclusively men, it is believed that many women also liked to look at these drawings.

Nishikawa Sukenobu Shunga. A man seduces a young woman; a shamisen lies on the floor behind him. Hand-colored woodcut with green background. The same print, but uncolored, is in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. (1711-1716)

Painting, horizontal scroll, shunga. One of 12 erotic encounters. An adult samurai and a young girl are hugging under a blanket. A woman straightens her bed. Ink, paint, gold and silver pigment, gold and silver leaf on paper. Not signed. (Early 17th century)

Many prints show sexual pleasure as mutual caresses. “They are strongly connected to everyday life,” says Clark. “Sex is often depicted in everyday settings, between husbands and wives.”

The print shown at the very beginning of the exhibition is such an example. “The Pillow Poem” by Kitagawa Utamaro (d. 1806) depicts lovers in a room on the second floor of a tea house. Their bodies are intertwined under luxurious clothes, and he looks passionately into her eyes. Her buttocks are visible from under the kimono.

“The Pillow Poem” (Utamakura), Kitagawa Utamaro. Shunga, colored woodcut. No. 10 of 12 illustrations of a printed folding album (set of individual sheets). Lovers in a closed room on the second floor of a tea house. Inscribed and signed. (1788)

A world of humor and satirical allusions

Kawanabe Kiyosai

However, much of shunga can hardly be considered naturalistic depictions of sex. This becomes obvious when looking at the huge genitals and the shocking and humorous situations depicted in many of the prints. There are many similarities between erotic shunga and what is known as warai-e, or “funny pictures.”

The left scroll of a pictorial triptych by Kawanabe Kiyosai (1831-1889) from the early Meiji era depicts a passionately embracing couple. The back shows a playful kitten with bare claws, whose attention is clearly drawn to the most sensitive parts of the male anatomy. The viewer can guess what happened next.

“In fact, I often wanted to laugh when looking at these pictures,” comments exhibition visitor Jess Oboiro. “For some reason, the Sunday crowd was in a kind of quiet reverie... although, naturally, that’s not the mood in which to view this type of art, is it?”

Humor in shunga can be both sharp and obscene. As with much of the folk culture of the Edo period, and certainly with the sexually explicit art of more modern eras, there is an element of rebellion.

“Shunga constantly turns to more serious genres of art and literature, parodying them, often as a joke, but sometimes with sharp political overtones,” says Clark.

One example is shunga versions of moral education books for women. Sometimes sexually explicit parodies are so similar that they appear to be made by the same artists and publishers as the originals. In fact, they actually come from the same publishing background.

However, when shunga satire got too close to the truth, censorship immediately appeared. Declared illegal in 1722, shunga was banned for two decades. Later, similar persecutions also occurred, but the art of shunga never completely disappeared. It skillfully used its semi-legal status to reach new levels of satire. Many shunga still amaze with their boldness and freedom of imagination.

One set in the exhibition features portraits of kabuki actors and enlarged images of their erect penises. The style of the pubic hair follows the actors' wigs, and the bulging veins match the lines of their makeup.

Shunga in modern Japan

“The simple-minded type” (Uwaki no so) from “Ten physiognomic types of women” (Fujin sogaku jittai), Kitagawa Utamaro. Colored woodcut with background covered with mica powder. The head of the girl wiping her hands on the cloth is turned, her chest is visible. Inscribed, signed, sealed and marked. (1792-1793)

Ironically, soon after shunga became famous in the West (Admiral Perry was given shunga as a “diplomatic gift”, and Picasso, Rodin and Lautrec were real fans of the genre), the Japanese decided that it was time to end this art. It was only in the 70s of the 20th century that an exhibition of shunga, which had been persecuted for years, was held in Japan.

This exhibition reaffirms the importance of shunga to all Japanese art. However, even now, according to researchers, it would be difficult to imagine an exhibition on the same scale in Japan as in the British Museum.

“It is clear that shunga was an integral part of Japanese culture until at least the 20th century,” says Andrew Gerstle, professor of Japanese studies at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London. “People are surprised that it is still impossible to hold such an exhibition in Japan itself.”

According to Clarke, the response to their exhibition in both the UK and Japan has been “absolutely phenomenal”. Only half the time allotted for the exhibition has passed, and they are already approaching the planned number of visitors.

Exhibition co-author Yano Akiko, a research fellow at the Center for Japanese Studies at SOAS, said the team had gone to great lengths to explain to visitors “a complex phenomenon that predates our era.”

“I was a little worried that we were trying to give too much information,” she says. “However, the majority of visitors seemed to really enjoy the exhibition - they fully accepted the content of the exhibition and understood what we wanted to convey. It was the best reaction we could imagine.”

(Original article written in English. Images from the collection of the British Museum).

Source

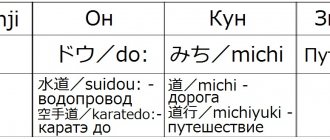

Shunga belongs to the ukiyo-e genre.

This is the main genre of Japanese woodblock prints. From a philosophical point of view, ukiyo-e

- this is a “cast of the moment.” Most often - pictures of everyday life, landscapes that convey emotions or mood.

Woodcut

— printing engravings on wooden blocks. This technique was borrowed by the Japanese from the Chinese in the 8th century and was originally used in the spiritual realm: as an image of Buddhist saints and illustrations of religious texts. At first they were black and white, later they appeared in color.

Engravings became widespread in the 16th century, when shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu founded the capital of his own shogunate - the city of Edo (modern Tokyo). A new class of citizens that emerged in the rapidly growing city became the main consumer of ukiyo-e: inexpensive pictures that looked like postcards.

The expressive prints that inspired European artists were not considered works of art and had little in common with traditional Japanese painting, which remained an expensive pleasure for the elite.

Ukiyo-e was often used for advertising and illustrations of popular low-grade literature, and they depicted kabuki actors.

Fans and admirers

It's funny, but among shunga fans there were both men and women of all classes. There were many superstitions around the explicit paintings. For example, samurai took shunga with them, believing that it would protect them from death. Merchants kept shunga in their warehouses, believing that images of men and women having sex would protect the warehouse from fire. However, what worked against this assumption was that almost all shunga-keeping groups had very limited access to the opposite sex: samurai lived for months in each other's company, and merchants traveled widely to purchase goods from other countries. Thus, perhaps the storage of shunga was purely sensual and not superstitious.

Shunga also served as a kind of “instruction” for the sons and daughters of wealthy families who were about to get married. However, this version also has opponents - often the lovers depicted in shunga had sex in such positions that the presence of bones in them raised serious doubts. Not to mention that it’s unlikely that a young bride will be happy to learn exactly how to have sex with an octopus.

In addition, in Japan there were also ordinary “manuals”, where more precise instructions were given both regarding sexual intercourse and regarding intimate hygiene.

For whom were shunga painted?

Like any unusual art, shunga had its admirers and persecutors. Samurai and merchants loved pornographic pictures; they say they carried them with them as amulets to protect them from death or fire. To be honest, this explanation raises serious doubts: representatives of both professions were forced to do without female company for a long time; most likely, carrying pictures with them had a more practical explanation.

Even now, with a huge number of pornographic photographs available almost freely on the Internet, these pictures can seriously excite both the imagination and the body.

Admirers of this type of painting were among all classes, genders and ages. Such freedom of morals worried the authorities so much that in 1661, and then in 1772, the drawings were banned, but, as one would expect, shunga did not go away, it just hid from prying eyes for a while.

By the way, such images shocked travelers; it was difficult to foresee that in the twenty-first century this painting would gain many fans in the West.

The Japanese are such entertainers

The shunga technique even now evokes very vivid emotions, although the modern viewer is quite sophisticated. What's the secret?

In the drawings, people are usually dressed; the Japanese do not consider the human body to be something very beautiful, and besides, they do not see anything shameful in nudity. But when only naked intimate parts of the body are visible, and even depicted in all anatomical details, in slightly enlarged proportions, it attracts the eye. It’s simply impossible to tear yourself away from these details!

It is said that these pictures were used by the children of wealthy citizens as a guide for newlyweds. If this is, in fact, the case, then their married life was quite eventful. Often pictures are accompanied by text explanations to better understand the meaning of what is happening. It is possible, of course, that the shunga had some influence on the younger generation, but for the newlyweds there were other guidelines for action.

Shunga, of course, did not become the Japanese Kama Sutra, but they excite the mind, body and imagination no less.

Shunga symbolism

Shunga was often accompanied by written explanatory texts and dialogues. But there are also other, not so straightforward symbols in the images. For example, the buds of plum flowers mean virginity, and the unfolded fabric means impending ejaculation.

It is curious, by the way, that people in most shunga are depicted dressed. This happens because the Japanese do not consider nudity particularly attractive: they often see each other naked in public baths. Additionally, clothing helps readers differentiate between courtesans and foreigners. Prints on clothing also often carry symbolism and also draw attention to exposed parts of the body - usually the genitals.

Shunga in the modern Western world

In 2013, the UK hosted a large exhibition of shunga at the British Museum. In Japan, only one museum dared to do this in 2015, despite the fact that the exhibition was offered to a dozen other museums that refused.

Shunga subjects have become quite popular; with Japanese prints in this style you can see not only pictures, but also dishes, clothes, and household items. What is considered indecent pornography in its homeland has become one of the hallmarks of Japanese art in other countries.

Although the heyday of shunga has long passed, undoubtedly, as real works of art capable of making an indelible impression on people, they will always arouse interest, along with the great creations of masters of painting from different countries and centuries.