Acquaintance, bows, introduction

Tell your friends. Help make the site more popular.

Speaking of acquaintances, one cannot fail to mention bows. Bows accompany almost any manifestation of etiquette: introduction, greeting, gratitude, request, apology, farewell. Most often, bows are made while standing, but depending on the situation, bows can also be made while sitting. It is believed that the lower the bow, the more polite it is. A standard bow has an angle of about 20-30 degrees. everyday bow (between acquaintances) - 15 degrees, ceremonial (in especially important cases) - from 45 to 90. Women and men bow slightly differently: men have their hands lying loosely at the seams, their toes slightly apart, and women fold their hands in front of them “boat”, socks can be slightly directed towards each other. When bowing, you need to remember the following rules:

1) The distance between interlocutors when bowing is about 3 steps (usually the distance between Russians is two steps)

2) Those younger in age and position bow first, more politely

3) Before bowing, the interlocutors look at each other with a polite, benevolent look, but without an open smile

4) While bowing, look down in front of you, back straight, legs together

5) The bow is maintained for about two seconds, after which the partners return to their original position and look at each other again.

Often when meeting people (especially in the business sphere), it is common to exchange business cards. This. This is probably due to the fact that native Japanese speakers are “visual learners” and it is very important for them not only to hear, but also to read the name of the person they are meeting.

When exchanging business cards, bow first with a standard or light bow

bow, perhaps with the words Hajimemashite...(name) des., bow again and hand over the card (visitors first). Usually the card is presented and accepted with the right hand; for special ceremonies, it is also possible with both hands. After exchanging business cards, they bow again and say the words Do:zo yoroshiku (yoroshiku o-negai shimas)

It is also necessary to note one important difference between Japanese etiquette and European etiquette: since in Japanese traditional society a woman occupies a lower position than a man, when meeting her through an intermediary, she is introduced to a man, and not vice versa, as is customary in the European tradition. However, Japanese partners can also observe European etiquette when meeting foreigners.

Let us now consider the speech patterns used when meeting:

| 自己紹介をさせていただきます。、、、です。 | Jikosho:kai sasete itadakimas. ...des. | Let me introduce myself, I... |

| (私は)) 、、、です/と もうしま す | Hajimemashite. (Watashi-wa) ... des (to mo:shimas) Hajimeite o me-ni kakarimas. (Watashi-wa) ...des (to mo:simas). | |

| どうぞよろしくお願いします どうぞよろしく よろしくいお願いします。 | Do:zo yoroshiku o-negai shimas. Do:zo yoroshiku. Yoroshiku o-negai shimas. | Please love and respect |

| (失礼ですが)、どちらさまですか。 お名前と名字はなんといいますか。 お名前はなんといいますか。 お名前はなんですか。 私の名前は、、、です(といいます)。 | Shitsurei des ga, dochira sama des ka? O-namae to myo:ji-wa nan to iimas ka? O-namae-wa nan to iimas ka? O namae-wa nan des ka? Watashi no namae-wa... des (to iimas). | Sorry. Who are you? What is your first and last name? What is your name? My name is.../my name... |

| お目にかかれてうれしいです。 | O-me ni kakarete ureshiy des. | Nice to meet you |

| 私の名刺をどうぞ。 私はこういうものです | Watashi-no-meishi-o dozo. Watashi-wa ko: yu: mono des. | This is my business card |

| あなたの名刺をお願いします。 | Anata no maishi o o negai shimas. | Please give me your business card |

| Home page 。 | Sumimasen, meishi no mochiawase-ga arimasen. Sumimasen ga, ima meishi-wa totto arimasen. | Sorry, but I don't have my business card with me. |

| ?ます 。 | O-uwasa/o-namae-wa kanegane ukagatte orimas. O-namae-wa...-san kara ukagatte orimas. | I've heard a lot about you. I heard about you from Mr. N. |

| あのかたはどなたですか。 あのかたは、、、です。 ご紹介しましょうか。 | Anokata-va donata des ka? Anokata-wa... des. Go-sho:kai shimasho:ka? | Who is this ? This… Should I introduce you? |

| どうぞお近付きになって下さい。 | Do:zo o-chikazuki-ni natte kudasai. | Meet me please |

| (ご)紹介します。 私の、、、をご紹介します。 | (Go)-sho:kai-shimas. Watashi-no...-o go-sho:kai-shimas. | Let me introduce my... |

| このかたは、、、さんです。 | Konokata-wa... san des. | This is... (introducing a person to someone) |

| こちらAさんです、こちらBさんです。 | Kotira A-san des, kotira B-san des. | This is Mr. A this is Mr. B |

Aさん、Aさんを紹介します。 | V-san, A-san-o sho:kai-shimas. V-san, kochira-wa watashi-no do:ryo: A-san des. | B, let me introduce you to A. B, let me introduce you to my colleague A. |

Found an error in the text? Select it and press Ctrl + Enter.

Kampai! Or "Bemo" in Japanese

Every country has a short toast that is appropriate in any situation.

Friends have gathered at the table; they don’t need unnecessary words. In Ukraine they will say: “Budmo!”, in Germany: “Prosit!”, in Britain: “Chirs!”, and in Japan – “Kampai!”. Those present will understand everything and drain their cups. But, unlike toasts in other countries, behind the Japanese “Kampai” there is much more than a wish for health and good luck. This is a centuries-old tradition, a complex ceremony, and deep respect for the people at the table.

What does “Kampai” mean and how does the Japanese alcohol ceremony take place?

If translated literally, “kampai” is a dry bottom. Something like our “drink to the bottom.” Its meaning is to encourage guests to drink, to move from the official part of the meal to the informal one. It is considered bad manners to touch alcohol before this toast has been made.

Ceremony - how the Japanese drink

First, the owner of the house or the oldest person at the table takes a wooden barrel of sake. Using a wooden hammer, in honor of the gods, he makes a hole. The drink is poured into glasses.

It is customary to pour for your neighbor - by filling his cup, you show respect. At your next toast, your neighbor will pour the drink for you. Unlike us, the Japanese pour glasses on the fly.

The pouring procedure is rather symbolic; people rarely drink to the bottom; with one glass of sake you can sit through the entire feast.

Then the oldest person at the table stands up and says: “Kampai!” and the guests raise their glasses to their lips. It is not customary to clink glasses; the glass is simply raised and brought to the lips. Although a toast sounds like “drain your glasses,” you don’t have to drink everything. The drink should be enjoyed, just like the food. The one who makes the toast must stand up. The rest of the participants can also stand up or raise a glass while sitting.

Next comes the informal part of the meal; the participants of the feast can be divided into groups based on their interests. But so that the general spirit does not disappear, each toast is accompanied by the traditional “Kampai!” For the second and subsequent times, any of the guests can make a toast. Therefore, the call “Kampai!” It would be more accurate to translate not as “Let’s drink to the bottom,” but as “Let’s drink together.”

What do they drink?

Sake is not a strong drink, but, like everything in Japanese cuisine, it is refined and difficult to prepare. This is not vodka or wine, sake is not a product of distillation or fermentation. In the classic drink, fermentation occurs due to the work of mushrooms, which gives the drink a very original taste.

The strength of sake is about 18-20°, but this is considered very high. Before serving, the hostess can add a little water to the drink, diluting it to about 15°. Served in ceramic dishes and drunk from ceramic cups, like shot glasses. The shape of the cookware may vary depending on the region of Japan.

Interestingly, sake can be served either chilled to 5 °C or heated to 50-60 °C. There are different traditions, and among the Japanese themselves there is still debate about how to drink sake correctly.

Some experts will tell you that you only need to heat a bad, cheap drink, since heat drowns out the aroma.

Others will tell you that, on the contrary, only when heated does the unique aroma reveal.

Fun party with Kampai

Although the strength of sake is very low, and they drink it little by little, the Japanese quickly get drunk. It is not customary for them to hide their condition or be ashamed of it. People begin to talk more and louder, and jokes are made that would be unacceptable in another environment. This is the whole essence of “Kampai” - after the first toast, the official part is considered completed, you can have fun, communicate and enjoy life to the fullest.

But no matter how long the feast drags on, no matter how much sake is drunk, in the morning all the participants come to work and look completely fresh.

There is simply no such thing as a “hangover” among the Japanese. Missing a day of work is considered a terrible shame; under no circumstances should such an outrage be allowed to happen.

And, even more so, none of the Japanese would think of “recovering their health” on the second day.

The Amazing History of the Kampai Tradition

The scientist Noritaka Kanzaki studied the Japanese alcoholic tradition. He managed to discover amazing facts - “Kampai” came to Japan from Europe. No source mentions the character “Kampai” until the mid-19th century. It was only after 1868, when Japan opened itself to the Western world, that references to the tradition that is now considered generally accepted appear.

In the West, the tradition of drinking at the same time appeared as proof that the drinks were not poisoned. Our ancestors also began to clink glasses in order to pour part of the drink from their cup into someone else’s, thereby confirming that there was no poison in it.

An ancient Japanese proverb says that “There are no gods who don’t drink.” Therefore, the Japanese, before the start of the feast, held a ceremony of treating the gods. None of the participants would have even thought of committing sacrilege and poisoning what the gods would drink.

Noritaki Kanzaki believes that the tradition of toasting was brought to Japan by British naval officers at the beginning of the last century. During the Russo-Japanese War, Great Britain acted on the side of Japan, among other military assistance, sending a large number of advisers. It is clear that the sailors and soldiers of the Allies shared not only the burden of battles, but also the joy of feasts.

Japanese officers liked the tradition of raising cups together, and they carried it throughout the country. Over time, the ceremony acquired national characteristics and began to look like an ancient one.

Let us also raise our cups together and shout “Kampai”!

Source: https://kampai.com.ua/kampay-ili-budymo-po-yaponski

Everyday etiquette and variability

A foreigner visiting Japan may feel uncomfortable at first, because the Japanese are very friendly in communication.

From childhood they are taught respect and tact. For example, if you entered someone's apartment, then you need to ask for forgiveness for the intrusion (“ojama-shimasu”), even if the owner himself invited you. The word “sumimasen” in everyday use means “forgive”, although it literally translates as “I have no forgiveness”, and is used everywhere. There are times when "sumimasen" is used as a greeting. For example, a visitor entering an empty cafe or restaurant will say: “Sumimasen!”, as if apologizing for such a blatant act that has no justification. Although one should not be deceived, such an exclamation also means something like “Hey, is anyone here?!”, pronounced as indignation due to absence from the workplace.

The word “sumimasen” has recently become increasingly used even instead of thank you, as gratitude for something, because with such a turn of phrase one can express both gratitude to people and regret that they bothered and showed care. In Japan, this word can be heard thousands of times a day, its true meaning has practically disappeared, and therefore, when a Japanese person is really uncomfortable and an action requires an apology, they use a completely different expression, which means: “I can’t even find the right words to express my regret to you.” "

Along with the word “sumimasen”, you can also often hear “shitsureishimas”. This is a fairly universal lexeme, which literally means “sorry,” but depending on the situation it can also have a slightly different meaning: “excuse me, I’m coming in,” “goodbye,” “sorry for bothering you.”

Acquaintance

When interlocutors first get to know each other, they usually first talk about themselves and express hope for mutual support. In Japanese this is called 自己紹介 - "jikosho kai", which can literally be translated as "self-presentation". A sort of self-presentation. an established pattern in Japanese society .

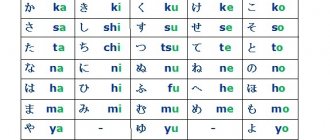

It should be noted that the Japanese language has several levels of politeness . Here, with the exception of some points, phrases of two levels will be presented. Polite/Formal - Suitable for all occasions. It is universal , at least in the initial stages. Informal is the level of politeness of speech among friends, close colleagues, and the like. Be careful in choosing your phrase - the wrong level of politeness will alienate a person or even offend him.