Ancient literature

Initially, myths and songs were common in Japan, which were transmitted orally. However, closer to the 7th century, everything changed. Emperor Tenji established higher schools where Chinese was taught. Soon, the written Japanese language emerged by borrowing and optimizing characters from China. Thus, by the 7th century, writing began to actively spread. As a result, monuments of Japanese literature began to appear.

The first Japanese work that has survived to this day is a chronicle called Kojiki. It was written by Yasumaro Ono in 712. The book contained various folklore, represented by songs, myths, fairy tales, legends, etc. In addition, the work also had historical value. Indeed, in the Kojiki the author left some historical legends and chronicles.

Another example of ancient Japanese literature is Manyoshu. The book was a huge collection of lyrics, which included more than 4,000 folk and original tanka poems.

LAI

Based on materials from websites

The main myths of ancient Japan are collected in two national epics: “Kojiki” (“Records of Ancient Deeds”), compiled in 712, and “Nihongi” (“Annals of Japan”), dating back to 720. Both epics were compiled at the command of rulers of the Yamato clan, who established themselves in power in the 7th century.

The most famous is the epic “Kojiki”. It consists of three parts, or scrolls. The myths of the first scroll are written down oral folk tales about the appearance of the first gods in the heavens and their creation of the Earth. These myths date back to the earliest period of Japanese history, called the Age of the Gods. The myths of the second and third scrolls are dedicated to the heroic deeds of heavenly descendants on Earth. Behind these actions one can already discern real episodes in the history of ancient Japan.

Mythological stories are also found in other ancient manuscripts, for example, in “Kogo Shuki” (“Excerpts from Ancient Stories”, 807), collected by the Imbe clan, in the manuscript “Fudoki” (“Records of Customs and Lands”), many such stories contain chronicle of Izumo province - “Izumo no kuni fudoki” (733). There are mythological subjects in “Sekou Nihongi” (“Continuation of the Chronicle of Japan”, 797).

The plots of ancient Japanese myths are partially found in the anthology of ancient Japanese poetry “Man'yoshu” (8th century) and in the religious court chants of norito, collected in the manuscript “Engi Shiki” (“Rules of Conduct of the Engi Era,” 10th century).

The myths collected in the Kojiki and Nihongi epics fall thematically into three large cycles. The first cycle contains myths about Takamagahara (High Sky Plain), where the first gods appeared. The second cycle of myths is associated with events that took place in the country of Izumo (present-day Shimane Prefecture). The god Susanoo was expelled from Heaven to this country for his misdeeds. And finally, the third cycle of myths is associated with the country of Tsukushi (modern Kyushu). It was here that the god Ninigi descended from Heaven to take control of Japan. Some researchers combine the first and third cycles of myths into a general cycle dedicated to the country of Yamato.

In the first cycle of myths dedicated to Takamagahara, the main ones are the myths about Izanagi and Izanami, Amaterasu and Susanoo. Izanagi and Izanami were the first Heavenly Deities we learned about. They were tasked with creating the earth's firmament from sea water and were given the Sacred Precious Spear. The drop that fell from the tip of this spear, condensed, formed the island of Onogoro, to which Izanagi and Izanami descended from Heaven and laid the foundation for life on Earth. They created eight islands that made up the territory of Japan. When Izanami passed away, Izanagi tried to rescue her from the Land of Darkness, but failed. Purifying himself from the filth of the Land of Darkness in the waters of the Tachibana River, he created the three main deities of Japanese mythology. From the washing of his left eye arose the sun goddess Amaterasu, from the washing of his right eye the moon god Tsukiyemi, and from the washing of his nose the god of elements and storms Susanoo.

The second myth of this cycle tells about the feud between Amaterasu and Susanoo for primacy in the heavenly divine pantheon. Amaterasu, frightened by the outrages of her brother, hid in the Heavenly Rocky Grotto, which is why night fell on earth. It was possible to lure Amaterasu out of the grotto only with the help of the sacred mirror of Yata. As punishment, Susanoo was expelled from Heaven to the country of Izumo, where he fought an eight-headed snake, defeated it and retrieved the sacred sword Kusanagi from its tail.

The second cycle of myths, associated with the country of Izumo, tells about the descendant of Susanoo - the earthly god Okuninushi, who ruled this country. First, he fought to maintain power with his brothers, and then with the goddess Amaterasu, who planned to send a heavenly governor to Izumo. This struggle ended with Okuninushi finally agreeing to accept the heavenly viceroy.

The third cycle of myths is dedicated to the descent from Heaven to Earth in the country of Tsukushi, the grandson of the goddess Amaterasu, the god Ninigi. Before this, Amaterasu presented Ninigi with three sacred relics of Heaven - the Magatama jasper pendants, the Yata mirror and the Kusanagi sword, which began to be revered on Earth as sacred relics of the Shinto religion and as regalia of imperial power. However, the first heavenly governor on Earth did not become famous for any heroic deeds; on the contrary, he even incurred the curse of the god Oyamatsumi, because of which the lifespan of heavenly governors on Earth began to be limited to the lifespan of ordinary mortals.

The first scroll of the Kojiki epic ends with the myth of Ninigi. The myths of the second and third scrolls of this epic already tell about the earthly affairs of the heavenly governors in Japan. Among them, the myths of Jimmu and Jingu stand out. Each of them already has certain historical justifications.

Jimmu, who, according to myth, was the great-great-grandson of Niniga, marched from Tsukushi to Yamato (present-day Nara Prefecture). His name opens a long list of rulers of Japan from the Age of the Gods; for the first time, dates of his reign appear: 660–585. BC. One of the most famous holidays in Japan, the Founding Day of the Empire (Kigansetsu), was associated with the subsequently calculated day of his accession to the throne. It was abolished during the occupation of the country after World War II, but was reinstated in 1966 as State Foundation Day (Kenkoku Kinenbi). The myth dedicated to Empress Jingu tells about her campaign of conquest in Korea, which she carried out at the command of the gods.

Japanese myths are in many ways extremely distinctive and original. For example, they do not contain a plot about the appearance of man on Earth. People, according to myths, became the descendants of deities who descended from Heaven to Earth. The myths of Japan introduce us to the fundamental concepts and values of Shintoism, the ancient national religion of the Japanese. They allow us to understand deeper and more specifically the psychology of the Japanese people, to get a clearer idea of the motivation for the behavior of the Japanese, their moral and spiritual values.

Kojiki (“Records of Ancient Deeds”) is the largest monument of ancient Japanese literature, one of the first written monuments, the main sacred book of the Shinto Triple Book, which includes, in addition to the Kojiki, “Nihongi” (“Annals of Japan”) and those burned during a fire in 645 “Kudziki” (“Records of past affairs”).

It is difficult to unambiguously determine the genre of this work, which is an example of the syncretism of ancient literature. This is a collection of myths and legends, a collection of ancient songs, and a historical chronicle.

According to the preface, the Japanese storyteller Hieda no Are interpreted and the courtier O no Yasumaro (d. 723) wrote down the mythological and heroic epic of his people, permeating it with the idea of \u200b\u200bthe continuity and divine origin of the imperial family. Work on the Kojiki was completed in 712, during the reign of Empress Genmei (707–715).

The author's list of “Kojiki” has not survived to this day. The oldest and most complete version of the fully preserved lists of all the Kojiki scrolls is the so-called “Book of Shimpukuji,” which received its name in honor of the Shimpukuji Temple in Nagoya, where it is kept. The creation of this version by the monk Kenyu dates back to 1371–1372.

Scroll 1. Chapter 1

When Heaven and Earth first opened, the names of the gods who appeared in Takama no hara - the Plain of High Heaven - were: Ame no minaka nushi no kami - the Ruler God of the Sacred Center of Heaven; behind him is Taka-mi-musubi-no kami - God of the High Sacred Creation; behind him is Kamimusubi no kami - the God of Divine Creation. These three gods appeared each on their own and did not allow themselves to be seen.

The names of the gods that came for them from what came to light like reed shoots, at a time when the earth had not yet emerged from infancy, and, like floating oil, rushed like a jellyfish [across the sea waves], were: Umasiyasikabi-hiko- zi-no kami - Youth-God of Beautiful Reed Shoots; behind him is Ame-no-tokotati-no kami - God Eternally Established in Heaven. These two gods also appeared each on their own and did not allow themselves to be seen.

The five gods mentioned above are special heavenly gods.

Scroll 1. Chapter 2

The names of the gods that appeared after them were: Kuni-no-tokotati-no kami - God Eternally Established on Earth; behind him is Toekumono no kami - the God of Abundant Clouds over the Plains. These two gods also appeared each on their own and did not allow themselves to be seen.

The names of the gods that came after them were: Uhijini no kami - God of Floating Mud, followed by Suhidaini no kami - Goddess of Sedimented Sand, her younger sister Tsunugui no kami - God of Solid Piles, followed by Ikugui no kami - Goddess of Life Melting Piles, younger sister; behind her is Oo-tonoji no kami - the God of the Great Chambers, behind him is Oo-tonobe no kami - the Goddess of the Great Chambers, the younger sister; behind her is Omodaru no kami - God of Perfect Appearance, behind him is Aya-kasikone no kami - Goddess, O Awe-Inspiring, younger sister; behind her Izanagi no kami - God Drawing to Himself, followed by Ideanami no kami - Goddess Drawing to Himself, the younger sister. From Kuni no tokotachi no kami to Ideanami no kami, the gods mentioned above , all together, are called the Seven Generations of Gods.

The two gods that appeared each on their own, which were mentioned above, are each called One Generation. Behind them, ten gods appeared in pairs, the two together, called One Generation.

Scroll 1. Chapter 3

Here all the heavenly gods gave their command to the two gods Izanagi no Mikoto and Izanami no Mikoto: “Finish the matter with this land rushing [on the sea waves] and turn it into firmament,” they said, bestowing a precious spear on them, and so instructed.

Therefore, both gods, having stepped onto the Heavenly Floating Bridge, sank that precious spear, and, rotating it, squelch-squish, kneaded [sea] water, and when they pulled [it out], the water dripping from the tip of the spear, thickened, became an island.

This is Onogorozima - the Self-Condensed Island.

Scroll 1. Chapter 4

[They] descended from heaven onto this island, erected a heavenly pillar, and built spacious chambers. Then [Izanagi] asked the goddess Izanami no Mikoto, his younger sister: “How is your body structured?”; and when he asked, “My body grew and grew, but there is one place that never grew,” she answered. Then the god Izanagi no Mikoto said: “My body has grown and grown, but there is one place that has grown too much. Therefore, I think, the place that has grown too much on my body, insert into the place that has not grown on your body, and give birth to a country. Well, shall we give birth?” When said so, the goddess Izanami no Mikoto “This [will be] good!” – answered.

Then the god Izanagi no Mikoto said: “If so, you and I, having walked around this heavenly pillar, will unite in marriage,” - so he said. So having agreed, immediately: “You go around to the right, I’ll go around to the left,” he said, and when, having agreed, they began to go around, the goddess Ideanami no Mikoto was the first: “Truly, a wonderful young man!” - said, and after her the god Izanagi no Mikoto: “Truly, a beautiful girl!” - said, and after everyone had spoken, [the god Izanagi] announced to his younger sister: “It is not good for a woman to speak first,” - so he announced. And yet [they] began the marriage affair, and the child that they gave birth [was] a leech child. This child was put in a reed boat and set sail.

Behind him Awashima - Foam Island was born. And they didn’t consider him a child either.

Scroll 1. Chapter 5

Then the two gods, after consulting, said: “The children that we have now given birth to are not good. “We need to present this before the heavenly gods,” they said, and so they went up together [to the Plain of High Heaven] and asked for instructions from the heavenly gods. Here the heavenly gods, having performed a magical act, expressed their will: “Because [the children were] bad, because the woman spoke first. Come down again and say it again,” they said. And then, they went back down and again, as before, walked around that heavenly pillar. Here the god Izanagi no Mikoto is the first: “Truly, a beautiful girl!” - said, after him the goddess Izanami no Mikoto, his wife: “Truly, a wonderful young man!” - she said. And when, having said this, they united, the child they gave birth to [was] the island of Awaji-no-ho-no-sa-wake.

Behind him, the island of Ie-no-futana, Double-named, was born. This island has one body, but four faces. Each face has its own name. Therefore, the country of Ie is called Ehime, the country of Sanuki is called Iieri-hiko, the country of Awa is called Oo-getsu-hime, the country of Tosa is called Takeeri-wake.

Behind him, the island of Okinomitsugo, the Three-Chinese, was born. Another name is Ame-no-oshikoro-wake.

Behind him, the island of Tsukushi was born. And this island, too, has one body, but has four faces. Each face has its own name. Therefore, the country of Tsukushi is called Shirahi-wake, the country of Toekuni is called Toehi-wake, the country of Hi is called Takehimukahi-Toyokujihine-wake, the country of Kumaso is called Takehi-wake.

Behind him the island of Iki was born. Amehitotsubashira is called differently. Behind him the island of Tsushima was born. Ame-no-sadaeri-hime is called differently. Behind him, Sado Island was born.

Behind him, the island of Oo-yamato-toeakizushima was born. Amatsumisora-toeakideune-wake is called differently. And so, because these eight islands were born before [others], they are called Oo-yashimaguni - the Country of the Eight Great Islands.

After this happened, they returned, and then the island of Kibi no Kojima was born. Takehikata-wake is called differently.

Behind him, the island of Azukijima was born. It's called Oo-no-de-hime differently.

Behind him, the island of Oo-shima was born. Oo-tamaru-wake is called differently.

Behind him, the island of Himejima was born. Amehitotsune is called differently.

Behind him the island of Thika was born. It is called differently Ame-no-oshi-o. Futago Island was born behind him. Amefutaya is called differently. From Kibi no Kojima Island to Amefugaya Island there are only six islands.

Scroll 1. Chapter 6

Having already completed the birth of the country, they now gave birth to the gods. And so, the name of the god born [by them] was Oo-kotooshi-o-no kami - God the Man of the Great Deed.

After him, Iwatsuchi-biko-no kami - the Youth God of the Rocky Earth - was born.

After him, Iwasu-hime no kami - the Virgin Goddess of Stony Sand - was born.

Behind her Oo-tohi-wake-no.kami - the God of the Great Entrance to the Dwelling was born.

After him, Ame-no-fuki-o-no kami - the God-Man of Heavenly Roofing - was born.

Behind him Oo-ya-biko-no kami - the Young God of the Great Roof was born.

Behind him, Kazamotsu-wake-no-oshi-o-no kami - the God-Husband of the Wind Averter - gave birth.

Behind him, the god of the sea - his name was Oo-wata-tsumi no kami - the God-Spirit of the Great Sea was born.

Behind him, the god of the straits - his name was Hayaakitsu-hiko-no kami - the Youth God of Early Autumn gave birth.

Behind him, Hayaakitsu-hime-no kami - the Virgin-Goddess of Early Autumn, gave birth to a younger sister.

From the god Oo-kotooshi-o-no kami to the goddess Akitsu-hime no kami, there are only ten gods.

These two gods, Hayaakitsu-hiko and Hayaakitsu-hime, divided among themselves, began to own - one the rivers, the other the seas. The names of the gods born [were] Awanagi no kami - God of Foam on Water, next Awanami no kami - Goddess of Foam on Water, next Tsuranagi no kami - God of the Bubbling Surface [Water], next Tsuranami no kami - Goddess of the Bubbling Surface [Water], next Ame-no-mikumari-no kami - Heavenly God of Water Distribution, next Kuni-no-mikumari-no kami - Earthly God of Water Distribution, next Ame-no-kuhizamochi-no kami - Heavenly God of Scooping Water, the following Kuni-no-kuhizamochi-no kami is the Earthly God of Scooping Water.

From the god Awanagi no kami to the god Kuni no kuhizamochi no kami, there are only eight gods.

Behind them, the god of the wind - his name was Shinatsu-hiko-no kami - the Youth God of the Wind gave birth.

Behind him, the god of trees - his name was Kukunoti no kami - the God-Spirit of the Trunks gave birth.

Behind him, the god of the mountains - his name is Oo-yama-tsumi no kami - God-Spirit of the Big Mountains gave birth.

Behind him, the goddess of the plains - her name was Kayano-hime no kami - the Virgin Goddess of the Grassy Plains gave birth. In another way, Nodeuchi no kami - the Deity-Spirit of the Plains is called.

From the god Shinatsu-hiko no kami to Nozuchi there are only four gods.

These two gods, Oo-yama-tsumi-no-kami and Nozuchi-no-kami, divided among themselves and began to own the mountains, the other the plains. The names of the gods born [were] Ame-no-sazuchi-no kami - Heavenly God of the Mountain Slopes, the following Kuni-no-sadauchi-no kami - Earthly God of the Mountain Slopes, the following Ame-no-sagiri-no kami - Heavenly God of the Mists in the Gorges, the next Kuni-no-sagiri-no kami - the Earthly God of the Mists in the Gorges, the next Ame-no-kurado-no kami - the Heavenly God of the Dark Crevices, the next Kuni-no-kurado-no kami - the Earthly God of the Dark Crevices , the next Oo-tomato-hiko-no kami is the Youth God of the Great Slope, the next Oo-tomato-hime no kami is the Virgin Goddess of the Great Slope.

From the god Ame-no-sazuchi-no-kami to the goddess Oo-tomato-hime-no-kami, there are only eight gods. The name of the born god behind them [was] Tori-no-ivakusubune-no kami - God of Boats Strong Like Rocks and Fast Like Birds from Kusu,” another name for Ame no torifune – Sky Bird-Boat.

After him Oo-getsu-hime-no kami - the Virgin Goddess of Great Food was born.

Behind her, Hi-no-yagihaya-o-no kami - God-Husband of Burning and Rapid Fire gave birth. In another way, Hi-no-kaga-biko-no kami - the Youth God of Luminous Fire is called. In another way, Hi-no-kagutsuchi-no kami - God-Spirit of Luminous Fire is called.

Because this child was born, the womb of [the goddess Izanami] was scorched, and she fell ill. The names of the gods, those who were born from her vomit, [were] Kanayama-biko-no kami - Youth-God of the Ore Mountain, the next Kanayama-bime-no kami - Maiden-Goddess of the Ore Mountain. The name behind them from the excrement of the appearing god [was] Haniyasu-biko-no kami - Youth-God of Viscous Clay, the next Haniyasu-bime-no kami - Maiden-Goddess of Viscous Clay. The name behind her from the urine of the goddess who appeared [was] Mitsuha-no-me-no kami - Goddess of Running Waters, the next Wakumusubi-no kami - Young God of Creative Powers. The child of this god is called Toeuke-bime no kami - the Virgin Goddess of Abundant Food. And so, the goddess Izanami no kami, because she gave birth to the god of fire, after all this, left. From Ame-no-torifune to the goddess Toeuke-bime-no kami, there are only eight gods.

In total, the god Izanagi no kami and the goddess Izanami no kami, both gods of the islands born together - fourteen islands, gods - thirty-five gods.

The goddess Izanami no kami gave birth to these [children] even before her departure. Only the island of Onogorozima was not born by her. And the leech child and Awashima Island were not considered children.

Scroll 1. Chapter 7

And so, the god Izanagi no Mikoto said: “My beloved wife-goddess! “I exchanged you for one and only child,” - so he said, and when, crawling in her heads, crawling at her feet, wept, the deity that appeared from his tears, under the shade of trees, on the hills that make up the foot of Mount Kaguyama, inhabited, is called Nakisawame no kami - the Weeping Goddess of the Swamps.

And so, [the god Izanagi] buried that retired goddess Izanami no Mikoto in Mount Hiba no Yama, [which stands] on the border between the country of Izumo and the country of Hahaki.

Here [the god Izanagi] drew the ten-cannon sword that girded him, and cut off the head of his son, Kagutsuchi no kami - God the Luminous Spirit. Then the blood that had stuck to the edge of the sacred sword fled onto the ridge of rocks, and the name of the god who appeared [was] Iwasaku no kami - God [of Thunder], Cleaving Rocks. Behind him is Nesaku no kami - the God of [Thunder], Cleaving the Foundations of [Rocks]. Behind him is Ivatsutsu-no-o-no kami - God-Man of the Stone Hammer. Three Gods.

Then the blood that stuck to the guard of the sacred sword that girded him also fled to the ridge of rocks, and the name of the god who appeared [was] Mikahayah-no kami - the God of Frightening Rapid Fire. Behind him is Hihayahi no kami - the Fire God of Rapid Fire.

Behind him is Takemikazuchi-no-o-no kami - the Valiant Frightening God-Man. Another name for Takefutsu no kami is the God of Valiant Sword Strike. Another name is Toefutsu no kami - God of the Mighty Strike with the Sword. Three gods.

Then the blood that had accumulated on the hilt of the sacred sword that encircled him leaked between the fingers of [the god Izanagi], and the name of the god who appeared [was] Kuraokami no kami - the Dragon God of the Gorges. Behind him is Kuramitsuha no kami - the God of Streams in the Valleys. From the god Iwasaku no kami to the god Kuramitsuha no kami, all eight gods described above are gods born from the sacred sword that surrounded him.

The name of the god that appeared in the head of the slain god Kagutsuchi no kami [was] Masakayama-tsumi no kami - God-Spirit of Steep Slopes. The name of the god who appeared behind him in the chest [of the god Kagutsuchi was] Odoyama-tsumi no kami - God-Spirit of the Kosogorov. The name of the god who appeared after him in the womb [of the god Kagutsuchi was] Okuyama-tsumi no kami - God-Spirit of the Depths of the Mountains. The name of the god who appeared after him in secret places [the god Kagutsuchi was] Kurayama-tsumi no kami - God-Spirit of Tesnin. The name of the god who appeared behind him in his left hand [the god Kagutsuchi was] Shigiyama-tsumi no kami - God-Spirit of the Wooded Mountains. The name of the god who appeared behind him in his right hand [god Kagutsuchi was] Hayama-tsumi no kami - God-Spirit of the Foothills. The name of the god who appeared behind him in the left leg [of the god Kagutsuchi was] Harayama-tsumi no kami - God-Spirit of the Plateau. The name of the god who appeared behind him in the right leg [of the god Kagutsuchi was] Toyama-tsumi no kami - God-Spirit of the Front Slopes.

From the god Masakayama-tsumi no kami to the god Toyama-tsumi no kami there are only eight gods.

And so, the name of the sacred sword with which he cut off [the head of the god Kagutsuchi] became Ame-no-ohabari - Heavenly Expanding Blade. Another name is Itsu-no-ohabari - the Sacred Powerful Blade.

Scroll 1. Chapter 8

Here [the god Izanagi], wanting to see his wife, the goddess Izanami no Mikoto, went after her to Yemi no kuni - the Land of Yellow Waters. And so, when [she] came out to meet him from the doors blocking the entrance, the god Ideanagi no Mikoto said: “My beloved wife-goddess! The country that you and I created is not yet fully created. Therefore, it must be returned to you,” he said. Then the goddess Izanami no Mikoto said in response: “It is regrettable [to me] that I did not come earlier. I tasted food from the hearth of the Land of Yellow Waters. And yet, my beloved hubby-god, I am embarrassed that you came here. Therefore, I will consult with the gods of the Land of Yellow Waters about my intention to return. Don’t look at me,” she said. Having said this, she went back to her chambers, and a lot of time passed, so that [her god Izanagi] became tired of waiting. And so, [he] pulled out a thick prong from the sacred shining comb that held a tuft of hair above his left ear, lit a fire and looked, entering, and [in her body] a countless number of worms swarmed and rustled, in the head of the Huge Thunder sat, in the chest Fire-thunder sat, in the stomach Darkness-thunder sat, in secret places Rupture-thunder sat, in the right hand [to the Earth] Striking thunder sat, in the left leg Rumble-thunder sat, in the right leg [Grass] Bending thunder sat, in total - eight gods of thunder appeared.

Then the god Izanagi no Mikoto became frightened at the sight of this and fled, and the goddess Izanami no Mikoto, his wife: “[You] have caused me shame!” - she said and set off the furies of the Land of Yellow Waters in pursuit of [him]. Then the god Izanagi no Mikoto took the black kazura net [from his head] and threw it, and immediately the fruits of wild grapes were born [from it]. While [the furies] were picking them up and devouring them, he ran further, and they again set off in pursuit, and then, this time, he pulled out a shining comb that held a tuft of hair above his right ear, and threw it, and immediately were born [from it] bamboo shoots. While the [furies] were pulling them out and devouring them, he ran on. Now those eight gods of thunder were given chase, and with them the army of the Country of Yellow Waters, numbering one thousand five hundred. Then [the god Izanagi] drew the sword of ten metacarpals that girded him, and, waving it behind his back, he ran further, and [they] followed him again, and when he reached the passage of Yemotsuhira, he picked three peaches [from the tree] that there was that passage, waited for [the army] and attacked [it], and all [they] ran back. Then the god Izanagi no Mikoto said to those peaches: “You! Just as they saved me, so must [you] save the human shoots of the earth that live in the Reed Plain-Middle Country, when they fall into the abyss of troubles and begin to grieve and complain!” - so he said and bestowed upon them the name Oo-kamu-zumi no Mikoto - Great Divine Gods-Spirits, so he called them. Finally, that goddess Izanami no Mikoto, the wife, herself set off in pursuit. Then [the god Izanagi] moved and blocked a rock that only a thousand people could handle, to that passage, and when [they] on both sides of that rock, standing opposite each other, dissolved [their] marriage, the goddess Izanami- but Mikoto said: “My beloved hubby-god! If you do this, I will strangle the human shoots in your country at a rate of a thousand a day,” she said. Then the god Izanagi no Mikoto deigned to say: “My beloved wife-goddess! If you do this, I will build one thousand five hundred houses a day for women in labor,” he deigned to say. Therefore, for every thousand people who certainly die a day, one thousand five hundred people are born a day.

And so, Izanami no Mikoto gave that goddess a name: Emotsu oo-kami - the Great Deity of the Land of Yellow Waters, she is called. And he also said: “Because you set off in pursuit, Chishiki no oo-kami - I name [you] the Great Deity of the Chase,” - so he said. And the rock with which the passage was blocked was called Chigaeshi no oo-kami - the Great God Who Turned Back [the Goddess], and also Sayarimasuemido no oo-kami - the Great God of the Door that Blocked the Entrance - that’s also what it’s called.

Therefore, the passage that was called Yemotsuhirasaka is now called the Ifuyazaka passage in the country of Izumo.

Page 1 of 2

deities mythology japan

Header photo: Demon God Bakan for KaijuX by LucasCGabetArts. Deviantart.com

If you find an error, please select a piece of text and press Ctrl+Enter.

Facebook Twitter Pinterest Google+ WhatsApp VKontakte

Classic literature

The next stage of Japanese literature was called classical. It lasted from the 8th to the 12th centuries. What is characteristic of this period? Japanese literature was strongly intertwined with Chinese. Most of the Japanese people were illiterate. It was for this reason that Japanese fiction spread among the aristocracy and high court circles. Perhaps the main feature of this era is that most of the works were written by women. It is for this reason that family and other decent motives predominate in classical Japanese literature.

The most striking example of literature of this era is “The Tale of the Beautiful Otikubo.” The book tells about the life of a Japanese Cinderella, who huddled in a tiny closet, while honoring the customs of her ancestors and moral precepts. Thanks to her high morality, the girl was able to rise from rags to riches, because a noble and rich gentleman fell in love with her.

If we talk about genre orientation, literature has moved away from folk art. Myths and fairy tales were replaced by higher genres: short stories, tales, short stories, etc. In the 10th century, the first Japanese novel was even published called “The Tale of Old Man Taketori.” It tells the story of an old woodcutter who meets a little girl who turns out to be an inhabitant of the Moon.

Medieval literature

This literary period lasted from the 12th to the 17th centuries. The power in the country has changed dramatically. The Mikado, who were the country's highly intellectual elite, were replaced by a military class called the shogun.

The country's literary activity began to decline rapidly. Genres such as the novel and Japanese poetry fell into oblivion. Memoirs of outstanding commanders and works of a historical nature were extremely popular. In general, Japanese literature became more violent and bloody. It is also worth noting that women writers did not take part at all in the medieval literary process of Japan.

"Genpei Josuiki" is a prominent representative of medieval Japanese literature. The work tells the story of the rise and fall of two families of aristocratic origin - Genji and Heike. The book is reminiscent of a Shakespearean chronicle in spirit. The work is characterized by brutal heroic battles, the interweaving of historical truth with fiction, the author's digressions and reasoning.

Contemporary Japanese literature

After the fall of the shoguns, the emperors returned to power. This led to the emergence of a new period in Japanese literature, which lasted until the mid-20th century. The land of the rising sun has become more open to another world. And this turned out to be the main factor for the development of literature. A characteristic feature of this period is the active influence of European ideas and trends.

First, the number of translations of European (including Russian) literature increased significantly. People wanted to learn about foreign culture. Later, the first Japanese works began to appear, written in a European style. For example, books such as “The Pillar of Fire,” “The Love Confession of Two Nuns,” and “The Five-Story Pagoda” are far removed from the Japanese classics. These works actively cultivated European ideology and lifestyle.

Japanese literature of the 20th century

A story about Japanese literature of the 20th century. it is necessary to start from the second half of the 19th century. It was then that a rapid leap was made from the Middle Ages to the Modern Age. This applies not only to literature, but to all aspects of Japanese life. The reason for this is the events called the Meiji Restoration.

Emperor Meiji signs a decree establishing the foundations of national policy

Reforms began, the main goal of which was to create a strong country and a strong army. Japan embarked on the path of industrial development following the Western model.

All these changes caused incredible fermentation of minds. Before the pressure of Western culture that poured into Japan, the intelligentsia was at first completely at a loss. The national culture seemed weak, backward, and helpless. Its foundations were questioned and ridiculed. “Advanced” youth converted to Christianity.

Since the 17th century. Japan was closed to foreigners, and Japanese were forbidden to leave their country under threat of death. However, in the 50s and 60s. XIX century under pressure from America, England, France and Russia, who advocated “free trade,” Japan was forced to abandon its centuries-old isolation. In 1867, the country was again led by the emperor, who had been relegated to the background under the shoguns (the title of the military rulers of Japan in 1192-1867). There was a kind of return to the “good old days”, so the era of the reign of Emperor Meiji began to be called the “Meiji Restoration”

In order to visit Europe themselves, average Japanese did not have the money, and therefore books became the main means through which they became acquainted with the life of the West. The Japanese learned very quickly and diligently, including foreign languages. One after another, translations and adaptations of world classics appeared in print. Western science was learned through Jules Verne, history through Alexandre Dumas and Walter Scott. The works of Shakespeare, Voltaire, and Rousseau were translated.

The first writers of the new era were people who combined translation activities with authorship. These writers-translators composed second-rate poetry in a European style and realistic novels. The Japanese really enjoyed reading about “ordinary” people in “ordinary” situations and with “ordinary” feelings. Indeed, in the literature of the previous era, prose storytelling was either openly didactic (Confucian) or adventurous. It turned out that a person’s spiritual life can also become a full-fledged subject of depiction.

Hashimoto Chikanobu. Concert of European music. 1889

The apprenticeship process did not last that long. Already at the end of the 19th century. works by writers of the naturalistic school appeared, retaining a certain significance to this day. The most prominent authors of the naturalistic movement are Tayama Katai (1871 - 1930), Tokutomi Roka (1868-1927), Shimazaki Toson (1872-1943). Their novels and stories tell about various aspects of Japanese life of that time: family, personal, social.

In Japan, an egoromaniac arose - “I-narrative”, that is, a first-person story about oneself. This genre reaches its maximum development in the novel “New Life” (1918) by Shimazaki, where the hero confesses his sinful passion for his niece. Egoromania was perceived as a completely new word in literature. However, after many years, its traditional Japanese basis turned out to be clearly visible: it was the same diary and essayistic literature of the Heian era, with its increased attention to the inner world of the author. Writers of the school of naturalism mercilessly depicted drunkenness, debauchery, and sexual anomalies. Since responsibility for the base in man was placed on society, this society itself, as a rule, appears in a very unsightly light, and the literature of naturalists is perceived as its decisive criticism. “The environment is stuck...” - this was the conclusion reached by naturalists who wrote mainly about losers caught in the snares that a soulless society had set for them.

Shimazaki Toson

The most remarkable writer of the Meiji era, Natsume Soseki (1867-1916), did not belong to any literary movements or groups. As an English teacher, in 1900 Soseki went to England on a scholarship from the Ministry of Education. There he spent two fruitful years studying Shakespeare and reflecting on the fundamental differences between Western and Far Eastern literatures.

Upon returning home, Soseki began lecturing at the University of Tokyo and began writing. His first novel, “Your Obedient Servant the Cat” (1905), brought him wide fame. In the extremely serious literature of the Meiji era, this was the first major work of satire. Studying English literature, so rich in invention and sarcasm, bore its “Swiftian” fruits, although, of course, the direct predecessor of this novel was “The Everyday Views of Murr the Cat” by E. T. A. Hoffman.

Koitsu Ishitawa. Grocery. 1931

The story is told from the perspective of a cat who lives in the house of an English teacher and watches its inhabitants and guests. The cat is very smart, attentive to life and witty. He laughs at the stupidity of literary novelties, the complacency of the nouveau riche, the pomp of officials, and the groveling before the West. Since the publication occurred during the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905), the jingoism of official propaganda also becomes the subject of the cat’s reasoning. He is even ready to form a cat brigade and immediately go to the front to scratch enemy soldiers.

Later, Soseki did not resort to open parody. In 1906, he published the story “The Boy” (“Botchan”) - the story of a young man who leaves the capital to teach on the island of Shikoku, and finds himself in the “normal” atmosphere of rank-honoring for Japanese society. The young teacher is trying to resist the inflated authorities and is ready to fight for justice. It is no wonder that after the publication of the novel, the word “botchan” became a household word in Japan.

Red Gate in Miyajima

Soseki's writing career lasted only eleven years. But the impression made by his books was so great that literary scholars often call these years the Soseki era. About 30 monographs dedicated to his work are published annually. And modern Japanese see the writer’s portrait every day - it adorns the 1000 yen banknote.

“Proletarian literature” became a significant phenomenon in social life. This movement, which arose under the influence of Soviet literature, was formed in 1929, when the Union of Proletarian Writers was formed in Japan. The most significant representatives of the new direction include Miyamoto Yuriko (1899-1951) and Kobayashi Takiji (1903-1933).

Illustration and cover for the novel “Your Obedient Servant the Cat” by Natsume Soseki

Although the works of proletarian writers, who consider life solely from the point of view of class struggle and opposition to the existing regime, can hardly be classified as masterpieces, their influence on the minds of their contemporaries was great. Almost all of the truly major Japanese writers treated proletarian writers with sympathy. Socialist ideas largely corresponded to the usual Confucian ideals of the structure of society, in particular its principle of the primacy of the public over the personal. That is why socialist ideology took deeper roots throughout the Far East than in the West.

The movement of proletarian writers became the last influential literary movement of the 20th century. Post-war literature of Japan is not so much the history of literary groups with their manifestos and literary hype, but rather the work of individuals. It is difficult even to list all the major Japanese writers of the post-war period. They are very different, but a unifying element can be identified - their work reflects the search for their own “I”, lost as a result of a radical change in the traditional way of life. Such a struggle to find oneself very often ended in defeat: many Japanese writers could not stand the confrontation with life and chose to voluntarily leave it. This is Akutagawa Ryunosuke, and Kawabata Yasunari, and Misima Yukio.

Geisha under the cherry blossoms. 1932

Having begun the 20th century with borrowings from the European tradition, known in the West only to specialists, Japanese literature ended the century as a full participant in the world literary process. This is evidenced by the awarding of Nobel Prizes to Japanese authors, and numerous translations of their books into European languages, and even the appearance in the 90s. non-Japanese authors who chose Japanese as their language of writing.

Japanese writers of the 20th century

- Akutagawa Ryunosuke (1892-1927)

- Kawabata Yasunari (1899-1972)

- Oe Kenzaburo (born 1935)

- Abe Kobo (1924—1993)

Share link

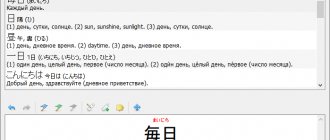

Japanese literature. Haiku

Japanese works of a lyrical nature deserve special attention. Japanese poetry, or haiku, has been popular throughout almost the entire period of literary development. The peculiarity of such works lies in the structure. According to the canons of the genre, haiku consist of 17 syllables, which form a column of hieroglyphs. The main theme of such works is a description of the beauty of nature or philosophical reflections. The most famous haijin are Takahama Kyoshi, Kobayashi Issa, Masaoka Shiki. Well, we can safely call Matsuo Basho the father of haiku.

Some genres of Japanese poetry

Some genres of Japanese poetry

Classical tanka have existed in written (and even longer in oral) form since the 8th century and have undergone many changes. The themes of such tanka are strictly regulated and, as a rule, they are songs of love or separation, songs written just in case or on the way, in which human experiences occur against the backdrop of the changing seasons of the year and are, as it were, fused (or rather, inscribed) into them.

Classic tanka contain five lines of 5 - 7 - 5 - 7 - 7 syllables, respectively, and this small space does not allow the entire associative series that arises in a Japanese reader (or writer) to be translated into other languages. Since tanka contains key words responsible for the emergence of certain associations, by translating all the meanings of these words into other languages, it is possible to achieve an approximate recreation of the original logical chain. It should also be noted that tankas, although they are a poetic form, do not have rhyme.

The tank form has gone through a lot in its lifetime, there have been ups and downs, various collections have been compiled, the very first of which was “Collection of Myriad Leaves” (“Man’yoshu”, 759), containing 4,500 poems. Gradually, tanka anthologies began to be published by order of the emperor, and tanka itself as a genre developed under the watchful eye of court poets.

By the end of the 19th century, tanka turned into rather monotonous repetitions of the same thing, which caused bitterness among adherents of traditions, and a desire to renounce and indignation among pro-Western poets. But it so happened that at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, two completely different poets (Yosano Akiko and Ishikawa Takuboku) were able to introduce new feelings and views into the strictly regulated volume of tanka, creating images that, although intertwined with the classical ones, carried freshness and unwornness .

In Japanese poetry there is another, no less important genre, which is called haiku (hoku). Haiku are three-line verses of 17 syllables, which were traditionally written on one line.

The first haiku appeared in the 12th century - in a comic form. The first poetry anthologies that appeared in the 8th and 10th centuries (The Collection of Myriad Leaves and The Collection of New and Old Songs of Japan) contain tanka poems written in an interesting manner: one poem was written by two authors, for example, the first three lines were written by one author , the last two are different. Or vice versa, the first author wrote two lines, the second author – three. And by the 12th century, these parts of one poem began to acquire independence, which led to the emergence of renga (“linked stanzas”), a genre based on strict rules. The rules of the rank were preserved thanks to the monument of that time - “The Current Mirror” (Ima kachami).

In the 13th century. serious renga began to be contrasted with comic, side trends in this genre. And after the appearance of the anthology “The New Collection of Mount Tsukuba,” renga became popular among townspeople and the peasantry, they included new layers of language, everyday themes, comic situations and common folk humor. This is how a new popular mass genre arose - haikai renga. And famous poets began the habit of leaving the last word for themselves when saying goodbye through a poetic joke - a haikai.

Later, haiku (i.e., the initial three stanzas of renga with 17 syllables) were separated from the renga chains and acquired independent meaning and a serious character. Comic haiku became a thing of the past with the appearance of the poet Matsuo Basho on the literary scene, and haiku itself became an independent serious genre, which, along with tanka, took a leading place in Japanese poetry and in the work of such poets as Yosa Buson and Kobayashi Issa.

The term “haiku” was put forward at the end of the 19th – beginning of the 20th centuries. poet and verse theorist Masaoka Shiki, who tried to reform the traditional genre. In the XVII – XVIII centuries. Haiku poetry was influenced by the Zen Buddhist “aesthetics of overstatement,” which forces the reader and listener to participate in the act of creation. In haiku poetry, a major role was played by the aesthetic principles formulated by Basho in the form of conversations with students and recorded by them: sabi (“sadness”) and wabi (“simplicity,” “simplification”), karumi (“lightness”), tariawase (“combination of objects”) , fuei ryuko (“eternal, unchanging and flowing, present”). These and other principles of poetry were developed at the end of the 19th century by the famous poet and verse reformer Masaoka Shiki and his students: Kawahigashi Hekigodo, Naito Meisetsu and Takahama Kyoshi. Masaoka Shiki's theory of haiku verse had a huge impact on the entire world of classical genres in the 20th century and is felt in the work of many poets today. Masaoka sought to preserve and revive the classical genre of tercets, entering into combat with outdated traditions; his main goal was to create a “true landscape”, and not just a schematic picture of nature.

In the era of passion for everything European, another genre arose in the Japanese culture of versification - kindaishi, which means “poetry of a new era.” In our collection, in addition to two classical genres - the tanka quintuple and the haiku tercet, there is another poetic genre - kindaishi, which arose in the era of passion for everything European. Different critics interpret the term "kindaishi" in their own way, but in general, in this case, we can talk about a poem written in the old literary language of Bungo or in the modern colloquial language of Kogo, in which there is an obvious metrical pattern based on traditional rhythmic patterns , although in different combinations.

Lyrical diary literature (nikki) in Japan has always been considered one of the most important genres, and the first work of this genre is recognized as “The Diary of a Journey from Tosa” (c. 935) by the poet and verse theorist Ki no Tsurasyuki. Diaries, as a rule, were not regular, and the entries were reproduced along with poetry. Poems from the relevant period were used, not just poems by the diarist. Moreover, diary entries were not always named explicitly; the title could be “Tale” or “Collected Poems.” A classic example is “On the Paths of the North” by Matsuo Basho - it is clearly a diary, but as we can see, nothing of the kind is written in the title.

The books "The Diary of Izumi Shikibu" and "The Diary of Murasaki Shikibu", two ladies-in-waiting of the imperial court and the best writers of their era, represent the medieval women's tradition of keeping diaries and, along with the "Diary of an Ephemeral Life" by the writer Mititsuna no haha, as well as the "Diary of a Travel to Tosa" consists of the four best diaries of the Heian era (IX - XI centuries). The diaries also include the poetic “Unsolicited Tale” of the 13th century. writers Nijo. All these inimitable examples of diary literature, pearls of Japanese literature, glorified this genre and created some of its laws. And in the 20th century, nikki found new life in the pages of works such as “Diary Written in Latin” by the wonderful tanka poet Ishikawa Takuboku.