Ashikaga Yoshimitsu 1358-1408

The war between the northern and southern courts continued for another half century after the death of Ashikaga Takauji. It was only possible to complete it thanks to the efforts of one of Japan's greatest historical figures. Yoshimitsu was the third shogun of the Ashikaga dynasty. He distinguished himself as a statesman during the construction of Kinkakuji, the temple of the Golden Pavilion in Kyoto. Yoshimitsu showed himself to be a cunning politician and a skilled commander, although his second aspect often remains underestimated.

Yoshimitsu became shogun in 1367. He actively waged military operations, and by 1374, supporters of the southern court were defeated almost throughout Japan. The position of the southern court remained strong only in Kyushu. Imagawa Sadayo, sent there with an army, was defeated. Then the young shogun personally led a new expedition and achieved an unconditional victory. Returning to Kyoto, Yoshimitsu took a number of steps that raised the prestige of his power to the highest level. He established diplomatic ties with the Chinese Ming Dynasty and began to conduct active trade. China during this period was experiencing a change of dynasty, it was a convenient moment to improve Sino-Japanese relations, spoiled due to attempts at the Mongol invasion. Yoshimitsu also actively fought against Japanese pirates, who terrorized not only Japan, but also the Chinese and Korean coasts.

Ashikaga Yoshimitsu

Of course, Yoshimitsu had to fight with competitors. A particularly serious rival was the Yamana clan, which made itself known in the last years of the war between the courts. Two brothers, Yamana Yoshimasa and Yamana Ujikiyo, challenged the shogun but were defeated. In 1391, their nephew Yamana Mitsuyuki made an attempt to challenge the power of the shogun. He attacked Kyoto, but Yoshimitsu managed to repel the attack. He then launched a counteroffensive and recaptured almost all of their possessions from Yaman, leaving them with only two provinces. This victory unusually strengthened Yoshimitsu's position, making it practically impregnable. Taking advantage of this, Yoshimitsu did not fail to put an end to the war between the northern and southern courts.

The southern emperor Go Kameyama was forced to abdicate and transfer the imperial regalia to the northern emperor Go Komatsu. Later, the descendants of the southern emperor rebelled several more times over the next fifty years, but they did not pose a serious threat to state power. Therefore, Yoshimitsu can rightfully be called the man who reconciled Japan.

Ashikaga Yoshimitsu once again had to face a serious military danger. Ouchi Yoshihiro (1356-1400) was one of Yoshimitsu's most loyal supporters, serving in Kyushu in 1374 and helping in the defense of Kyoto against Yaman Mitsuyuki's army in 1391. He led the negotiations that ended the confrontation between the courts. But in 1399, rivals of the Ashikaga clan managed to instill in him the idea that he was the one worthy to be shogun. As a result, Japan began its first major war since the end of the Nanbokucho War. Yoshihiro was supported by areas in western Japan. He also managed to establish cooperation with the pirates who sailed in the Inland Sea. Ouchi Yoshihiro carefully planned the upcoming campaign. He secured his rear by concluding the necessary alliances. He attracted to his side all those dissatisfied with the existing government. Among those who went over to his side was his former opponent Yamana Mitsuyuki. Yoshihiro marched east and linked up with Mitsuyuki near the city of Sakai, near what is now Osaka. They fortified the city with wooden walls and towers, and also dug wells in case of a possible siege.

Yoshimitsu began negotiations with the rebels, but when the negotiations reached a dead end, he began to lay siege to the city. Sakai was a port city, so Yoshimitsu lured several pirates to his side so that they would cut off sea communications, and he himself began an assault on the city. But they failed to take the city by storm, so they had to begin a systematic siege. By mid-January 1400, strong northerly winds began to blow. This allowed government troops to use the most formidable weapon - fire. The city was engulfed in fire. Soon the assault on the city began, the rebels were defeated, and Yoshihiro committed suicide.

Ashikaga Yoshimitsu achieved a lot through political methods, but at the same time he was also a talented commander. The expedition to Kyushu and the siege of Sakai convincingly testify to this. If Yoritomo was a politician, and Yoshitsune was a warrior, then Ashikaga successfully combined both of these qualities. He was a real shogun - politician, warrior and esthete. He died suddenly of illness in 1408 at the age of 50. His role in Japanese history is truly unique.

Ashikaga Shoguns

Akamatsu Norisuke, son of Norimura, used a banner with a prayer to Hachiman inscribed on it.

Ashikaga Shoguns

traced their descent from Minamoto—a prerequisite for candidates for the post of shogun—and asserted it by using a heraldic symbol in the form of an invocation of Hachiman Dai Bosatsu, the patron saint of Minamoto, depicted on their banners. This very ancient sign was adopted by the first samurai who took the family name Ashikaga. This samurai was Minamoto Yoshikuni (d. 1155), son of Minamoto Yoshiie (1041 - 1108), who settled in Ashikaga in the province of Shimotsuke and took his surname from the name of the place. Of course, the use of calls to Hachiman as a heraldic sign was not the exclusive privilege of the Ashikaga - these calls were also inscribed on the flags of the Ashikaga's contemporaries, the Akamatsu family, which played a significant role in the social and political life of Japan starting from the mid-14th century. and later. Akamatsu Enshin Norimura (1277–1350) used a simple hata jirushi with the inscription "Hachiman Dai Bosatsu" above the character "matsu". In this sign, the first letter of the name Hachiman - ha - was formed by two doves, just as in the sign of Kumagai Naozane described above. Enshin initially fought for Emperor Go-Daigo, but when he was denied a reward, he switched to the service of the Ashikaga and participated in the Battle of Minatogawa in 1336. Akamatsu Norisuke (1312-1371), Enshin's son, used a banner with ink inscribed on it a prayer to Hachiman and the date - “Genko 2” (1332). However, there was one heraldic device that belonged exclusively to the Ashikaga clan. This sign was the mon in the form of a kiri, stylized paulownia, which was originally the imperial coat of arms, second in importance after the imperial chrysanthemum. The Ashikaga always supported the northern court, and mon kiri was granted to them by the first "northern emperor" whom they served. Over the years, the mon kiri came to symbolize imperial service, and following the fall of Ashikaga in 1568, other commanders (the most famous of whom was Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the future unifier of Japan, a man of humble origins that excluded him from becoming shogun) began to adopt it as a heraldic device. sign. However, during the 14th-15th centuries. only the Ashikaga used mon in the form of kiri, which was usually depicted in black paint on white banners.

The only exception seems to be the symbol on the flag of the last Ashikaga shogun, Ashikaga Yoshiaki (1537-1597), consisting of a red sun disk and the ancient Ashikaga sign - a call to Hachiman. Representatives of the junior Ashikaga branch living in Kamakura, descended from Ashikaga's young son Takauji and therefore deprived of the right to nominate their candidates for the position of shogun, used the same mon as members of the senior branch of the clan. Thus, Ashikaga Shigeuji (1434-1497) waged a long-term internecine war on the land of Kanto with Ashikaga Masatomo (1436-1491), brother of the shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa (1435-1490). Shigeuji was based in the city of Koga and was titled Koga-kubo ("governor in Koga"). Their protracted conflict coincided with the more well-known Onin War for Kyoto. The battle banner of Ashikaga Shigeuji was the hata jirushi, marked simultaneously with images of a kiri and a solar disk (see color illustration of the OT). Besides the ruling clan led by the shogun, other clans also used ancient mon's given to their ancestors, among which the Chiba are prominent. Chiba Tanenao, who died in 1455, supported Koga-kubo Ashikaga Shigeuji, and when the latter was defeated, he committed suicide along with his son.

Banner of Tanenao

decorated with a heraldic sign in the form of a star and crescent, reminiscent of the miraculous salvation of their ancestors several centuries before the time being described.

GENERAL HISTORY

The second shogunate in Japan arose during long-term strife between the princes of noble houses. Over the course of two and a half centuries, periods of civil strife and the strengthening of centralized power in the country alternated. In the first third of the 15th century. the position of the central government was the strongest. The shoguns prevented the military governors (shugo) from increasing their control over the provinces. To this end, bypassing the shugo, they established direct vassal ties with local feudal lords, obliging the shugo of the western and central provinces to live in Kyoto, and from the southeastern part of the country - in Kamakura. However, the period of centralized power of the shoguns was short-lived. After the murder of shogun Ashikaga Yoshinori in 1441 by one of the feudal lords, an internecine struggle unfolded in the country, which developed into the feudal war of 1467-1477, the consequences of which affected the whole century. The country is entering a period of complete feudal fragmentation.During the years of the Muromachi shogunate, a transition took place from small and medium feudal land ownership to large ones. The system of fiefdoms (shoen) and state lands (koryo) is in decline due to the development of trade and economic ties, which destroyed the closed boundaries of feudal estates. The formation of compact territorial possessions of large feudal lords - principalities - begins. This process at the provincial level also followed the growth of the holdings of military governors (shugo ryokoku).

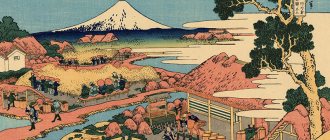

During the Ashikaga era, the process of separating crafts from agriculture deepened. Craft guilds now arose not only in the capital region, but also on the periphery, concentrating in the headquarters of military governors and the estates of feudal lords. Production focused exclusively on the needs of the patron was replaced by production for the market, and the patronage of powerful houses began to consist of providing a guarantee of monopoly rights to engage in a certain type of production activity in exchange for the payment of sums of money. Rural artisans move from a wandering to a sedentary lifestyle, and specialization in rural areas arises.

The development of crafts contributed to the growth of trade. Specialized trade guilds emerged, separated from the craft guilds. From the transportation of tax revenue products, a layer of Toimaru merchants grew, which gradually turned into a class of intermediary merchants who transported a wide variety of goods and engaged in usury. Local markets were concentrated in the areas of harbors, ferries, postal stations, and shoen borders and could serve an area with a radius of 2-3 to 4-6 km.

The capitals of Kyoto, Nara and Kamakura remained the centers of the country. According to the conditions of their emergence, cities were divided into three groups. Some grew out of postal stations, ports, markets, and customs posts. The second type of cities arose around churches, especially intensively in the 14th century, and, like the first, had a certain level of self-government. The third type were market settlements at military castles and headquarters of provincial governors. Such cities, often created at the will of the feudal lord, were under his complete control and had the least mature urban features. The peak of their growth occurred in the 15th century.

After the Mongol invasions, the country's authorities set a course to eliminate the country's diplomatic and trade isolation. Having taken measures against Japanese pirates attacking China and Korea, the bakufu restored diplomatic and trade relations with China in 1401. Until the middle of the 15th century. the monopoly of trade with China was in the hands of the Ashikaga shoguns, and then began to go under the auspices of large merchants and feudal lords. Silk, brocade, perfumes, sandalwood, porcelain and copper coins were usually brought from China, and gold, sulfur, fans, screens, lacquerware, swords and wood were sent. Trade was also carried out with Korea and the countries of the South Seas, as well as with the Ryukyu, where a unified state was created in 1429.

The social structure in the Ashikaga era remained traditional: the ruling class consisted of the court aristocracy, the military nobility and the top clergy, the common people - from peasants, artisans and traders. Until the 16th century classes and estates of feudal lords and peasants were clearly established.

Until the 15th century, when there was a strong military government in the country, the main forms of peasant struggle were peaceful: escapes, petitions. With the growth of principalities in the 16th century. An armed peasant struggle also arises. The most widespread type of resistance is the anti-tax struggle. 80% of peasant uprisings in the 16th century. took place in the economically developed central regions of the country. The rise of this struggle was also facilitated by the onset of feudal fragmentation. Mass peasant uprisings took place in this century under religious slogans and were organized by the neo-Buddhist Jodo sect.